Regular followers might recall that I asked for help shipping an item from Coeur d’Alene, Idaho here to the Carolinas back in April. Well, it arrived yesterday.

We now have an Auxiliary Power Unit for Lucky Thirteen.

As early as 4 am, the first clue that a USAAF heavy bomber strike was about to begin was usually the sounds of ground crews starting their APUs. Nicknamed the “putt-putt,” the APU generated 28.5 DC volts – the same voltage produced by the aircraft’s engines – allowing ground crews to service their bombers without draining the batteries or continuously running the engines.

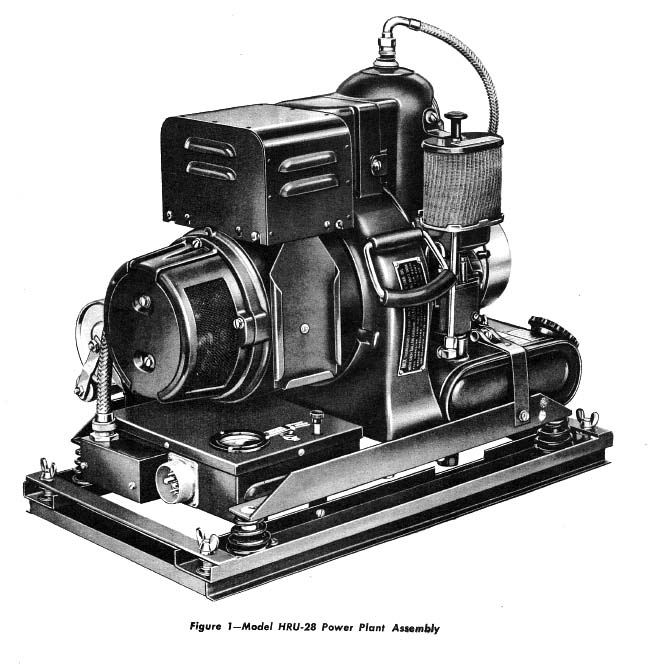

The Boeing B-17’s standard APU was the Type C-10, the Army designation for the HRU-28 and HRU-28A generators. Similar to a large lawnmower engine, these units were appropriately manufactured by the Homelite Corporation of Port Chester, New York. Started in 1921, the ‘Home Electric Lighting Company’ originally marketed generators as a way to provide electricity to homes in rural areas. However, they are best known as the originator of the portable chainsaw, which it premiered in 1946. Homelite is currently a subsidiary of China-based Techtronic Industries, still producing chainsaws, weed trimmers, and leaf blowers to this day.

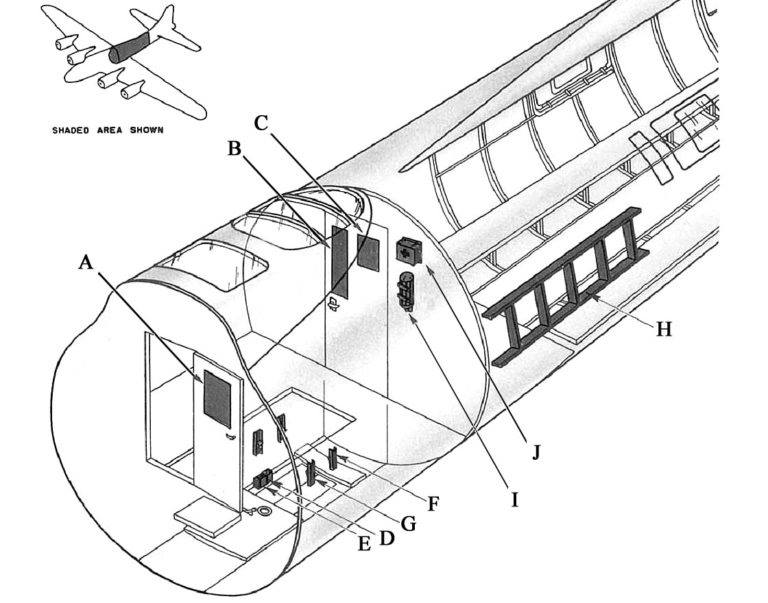

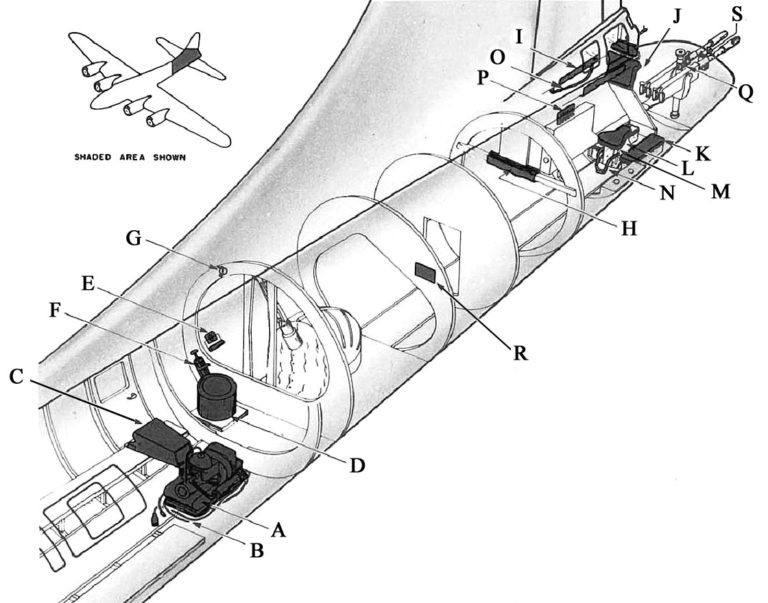

The B-17’s APU was located in the aft fuselage, directly across the main entry door next to the chemical toilet. The APU was one of several pieces which came standard with the bomber, but was usually removed and kept on the ground by maintenance personnel. Other ground pieces which came standard included the ladder, window covers, intake plugs, and various tool kits.

Most of today’s surviving APUs are HRU-28As, being distinguishable from the standard HRU-28 by their air filters. However, wartime photos reveal that the older HRU-28 was the more common model. It took us some time to locate an earlier variant, so we were truly fortunate to acquire such a well-preserved example from motorcycle collector Brett Samms. Brett’s dad, TSGT Herbert C. Samms, served as an aerial photographer with the 2nd Reconnaissance Squadron, a Consolidated B-24 unit attached to the US 5AF for aerial mapping. It is worth noting that the B-24 used the same APU as the B-17, mounting the unit by the nose wheel.

Fortunately, Brett was due to ship a pair of motorcycles to Washington, DC, hiring the services of Chris Hesthaven of Lugnut Transport. Chris was kind enough to piggyback the HRU-28 on said trip, traveling over 4,000 miles, hopping through cities like Milwaukee, Dallas, and Orlando before arriving here yesterday morning. Wow.

We do intend to restore this unit – and we will keep you posted as we do so – though, admittedly, it does not appear that she will need much work. To this end, we would like to thank our friend Patrick Hibbard of Warbird Manuals. The HRU-28’s manual is well-known in the small-engine community for its rarity, so the fact that Patrick was able to locate and scan one will be a massive aid to our project. If you would like a copy, we highly suggest reaching out to him.

Special thanks to Brett, Chris, and Patrick for their help in acquiring this rare piece!

The newly-arrived HRU-28 Auxiliary Power Unit sits in my living room.

The unit is 20.5″ tall, 16.875″ wide, 24.375″ long, and weighs 113 lbs.

Note the air filter on the left. The late-war HRU-28A had a hard-shell air filter.

Photo taken 8 August 2022.

MSGT Clyde Dewald (standing) and SSGT Robert Morgan with the HRU-28 APU for Good Enuf (42-5430, 303BG).

Good Enuf was lost when rammed by a FW-190 over Wilhelmshaven, Germany on 11 June 1943.

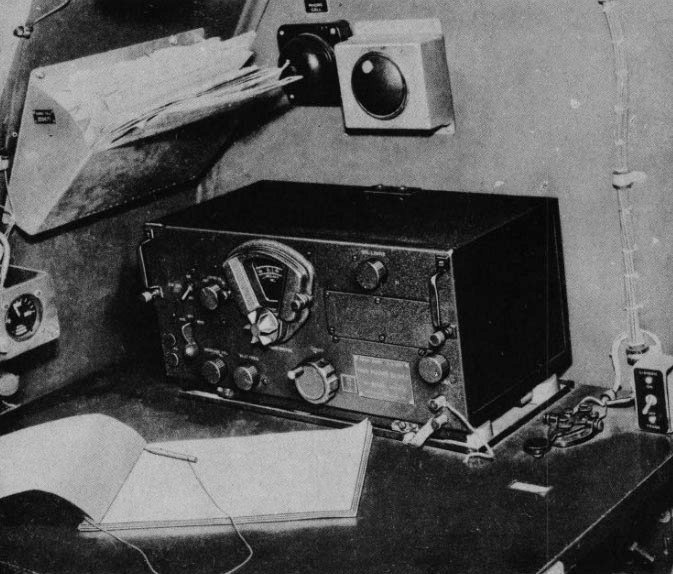

Note the long antenna under the nose. This is the nondirectional whip for the aircraft’s SCR-269 radio compass. This is one of the tiny few radio gear pieces we have yet to locate. If you can help – either by finding an original or fabricating a new one – please let us know!

The newly-arrived HRU-28 Auxiliary Power Unit sits in my living room.

Note how the cardstock dataplate has broken off the rivets on one side due to shrinkage.

Photos taken 8 August 2022.

The newly-arrived HRU-28 Auxiliary Power Unit sits in my living room.

Note the plug tucked under the right side. At first we thought this was a homemade addition. Nope. The manual actually suggests jerry-rigging a light bulb to ensure the generator is producing power.

Photo taken 8 August 2022.

Manual illustration of the HRU-28 Auxiliary Power Unit.

Crew photo featuring Brett’s dad.

TSGT Herb Samms is on the front row, kneeling on the far left. The 2PRS was stationed in New Guinea and the Philippines and their unit patch – a squirrel dodging bullets while holding a camera and a map – has been painted by the navigator’s window on this Consolidated F-7.

The F-7 was the photographic reconnaissance variant of the Consolidated B-24, being used for aerial mapping and post-strike target analysis.

An aerial photographer aboard a Consolidated F-7 (reconnaissance B-24).

The camera appears to be a Type K-17 – the same type donated by our friend SSgt Max Pearsall for Lucky Thirteen. All we lack for the B-17F’s camera bay is the Type A-2 Vertical View Finder and the camera’s shock mount (either a Type A-8 or Type A-11).

Yankee Doodle (41-9023, 97BG) undergoing maintenance. Yankee Doodle famously led the second formation of the US 8AF’s first heavy bomber strike on 17 August 1943.

Note the HRU-28 APU under the aircraft’s nose.

Also note the Boeing nacelle ladders. We replicated the ladder originally issued to Lucky Thirteen back in 2019.

The completed Boeing Nacelle & Entry Ladder sits outside our hangar at Asheville Regional Airport.

Photos taken 19 September 2019.

Pages from the manual show where the Boeing Nacelle & Entry Ladder and the HRU-28 Auxiliary Power Unit were originally stowed.

A Life magazine photo of a waist gunner aboard an E or early-F model B-17. In the back, where the APU was normally mounted, is a pair of platforms clipped to the wall. These ‘nacelle platforms’ were clumsy and dangerous for mechanics to work on, and were quickly discarded by Boeing.

Note the chemical toilet. The area around the toilet has been sprayed with asphalt varnish to protect the aluminum from urine. We are still in need of a chemical toilet for Lucky Thirteen, so if you can help with this, please let us know!

One of the wildest ground crew pieces in our collection is this Type C-1 Instrument Testing Cart, donated by our friend Andy Rivera.

Here Andy’s donated C-1 Instrument Testing Cart sits outside our hangar for some beauty shots.

Photo taken 28 October 2020.

Ground crews use a Type C-1 Instrument Testing Cart with Oklahoma Okie (42-29921, 91BG).

This aircraft was shot down over Cognac, France on 23 March 1944.

An armorer installs fuses to a series of 500 lb bombs for a July 1943 strike. These bombs are older models, being painted bright yellow to indicate their high explosive content. Later bombs merely used colored bands. Note the HRU-28 APU behind him.

Also note the SCR-269 whip antenna (mentioned earlier) as well as the bomb hoist rack on the ground under the bomb bay.

We might have some news regarding the hoist rack for Lucky Thirteen soon….

Today’s update covers some of the oxygen panels aboard Lucky Thirteen.

Longtime followers might remember that despite the metal working talents of guys like Ray Moore Jr., Bob Hachmann, and Bob Jacoby, I (Gerad Blume) have little experience with metal work. Rather, I come from a family of carpenters, and as such, my dad and I have done all the woodwork for Lucky Thirteen. This includes the placeholder instrument panel which we made to hold the various gauges while Bob Hachmann completes the panel housing. Of course, the actual instrument panel faces were not made of wood – they were made of phenolic.

Arguably history’s first commercial plastic, phenolic was a synthetic polymer made from carbolic acid and formaldehyde. The basis for such trade names as Bakelite and Micarta, phenolic was most often used to create laminates. Canvas-based phenolic laminates were particularly common during the war, going beyond mere circuit boards (the most common usage) to include any application where a lightweight alternative to aluminum or wood was needed.

Because we had yet to work with such material, we thought it worthwhile to begin fabrication of the bomber’s various oxygen panels – starting with those with phenolic faces. Setting aside the primary instrument panel and the bombardier’s oxygen panel (which is an unusual size), the positions completed here are the navigator, flight engineer, radio operator, two radio compartment passengers, and two waist gunner stations.

Except for the engineer’s and waist gunners’ panels, said oxygen panels were all similarly constructed. A phenolic faceplate, painted black on the outer side, was mounted to a wooden bracket, painted Boeing bronze green, made using .125 Douglas Fir plywood braced with spruce supports. The phenolic proved surprisingly easy to work with! There will be a great deal more work with phenolic in the future though, unfortunately, the material is rather expensive.

The finished oxygen panels for Lucky Thirteen.

Photo taken 25 July 2022.

The navigator’s oxygen panel.

While the flow indicator was later replaced by the blinker type, the panel itself remained largely unchanged since its introduction in early-1943.

Photo taken 25 July 2022.

A rather strange photo of a navigator aboard a Boeing B-17F. Not only has the factory table not been replaced by the Cheyenne type – as was typical practice for F models – but the airman is wearing a constant flow oxygen mask aboard an aircraft clearly equipped with a demand flow system. It is likely that this photo was staged.

What is also noteworthy is the additional gear aboard this aircraft, both behind the navigator and to the right of his oxygen panel.

Photo taken 5 November 1943.

The flight engineer’s oxygen panel. Unlike most of the other panels, this one has no wooden backing, instead mounting to the wall via a set of aluminum spacers.

This hook-up was intended for use when the engineer was not operating the upper turret.

Photo taken 25 July 2022.

Because space was so limited, few wartime photos clearly show the layout of the B-17’s cockpit.

This photo, taken from the bomb bay, peering into the cockpit, shows the flight engineer sitting behind the co-pilot’s seat. Though not visible, the flight engineer’s oxygen panel would be to the right of where he is sitting.

Note the oxygen bottle hanging above. The upper turret on this aircraft is an early Type A-1, which carries its own oxygen tank (on a swivel) and must be recharged at regular intervals. Later turrets used a swivel joint to pipe in oxygen directly from the aircraft’s main supply.

The radio operator’s oxygen panel. The three holes on the left are for mounting the Type A-12 Oxygen Regulator.

Photo taken 25 July 2022.

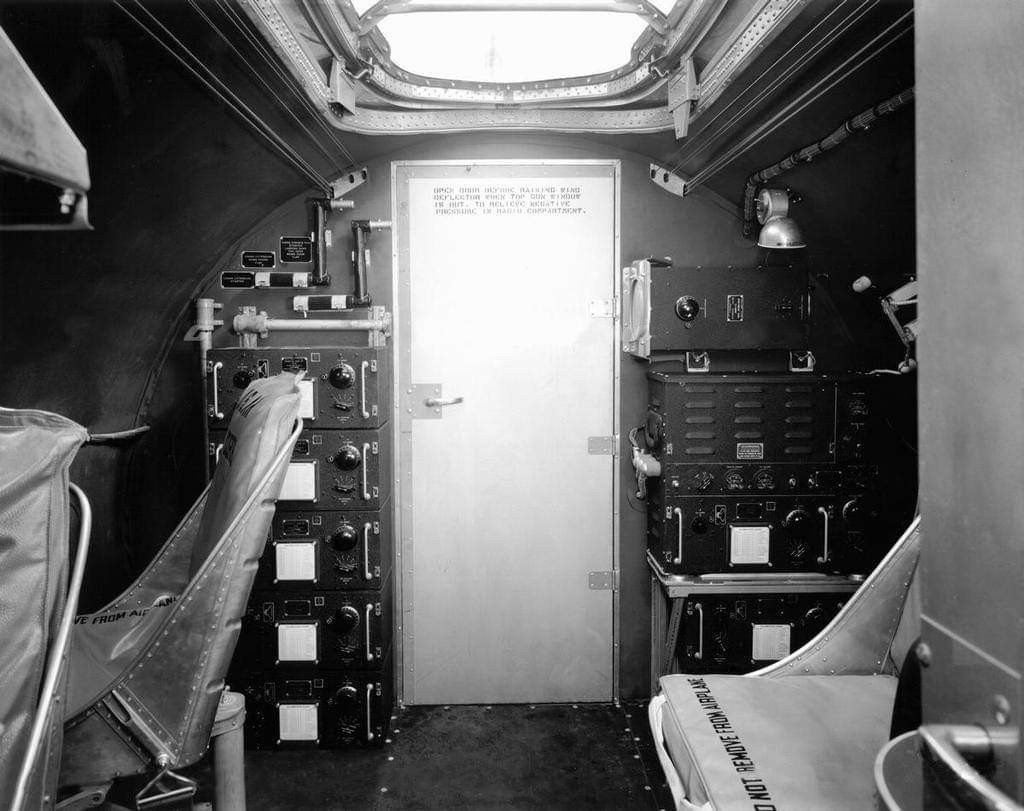

A manual photo showing the radio operator’s position aboard a late-F model. The radio operator’s position aboard Lucky Thirteen will be identical to this, though the ashtray will be mounted lower and the switch inlayed into the table.

Note the oxygen panel to the left of the table.

One of the two spare oxygen panels mounted in the radio compartment. This particular panel is identical to the one used by the radio operator on the opposite wall.

Note the canvas strap. Each oxygen station came with a canvas strap to clip the hose onto when not in use. As per blueprint spec, the ends are dipped in bee’s wax to keep it from fraying.

Photo taken 25 July 2022.

A photo taken aboard a B-17G Pathfinder toward the end of the war.

While this radio passenger oxygen panel is different than those used on F-model B-17s (as it has an intercom jackbox), note how the leftmost oxygen hose is clipped to the canvas strap.

A third oxygen panel is visible mounted above the radio tuning units, behind the modified strike camera. This panel was jerry-rigged from an old waist gunner’s panel.

The second spare oxygen panel mounted in the radio compartment.

Photo taken 25 July 2022.

A factory photo taken aboard an E-model B-17.

The B-17 was designed to allow for a pair of passengers in the radio operator’s compartment, and for a time, seats were even provided for these positions.

Because these seats were usually removed, Boeing quickly abandoned the practice. This was wise – crashlanding procedure required the crew to gather on the floor in this area. Still, oxygen provisions for two passengers remained a common practice.

One of the two waist gunner’s oxygen panels.

Photo taken 25 July 2022.

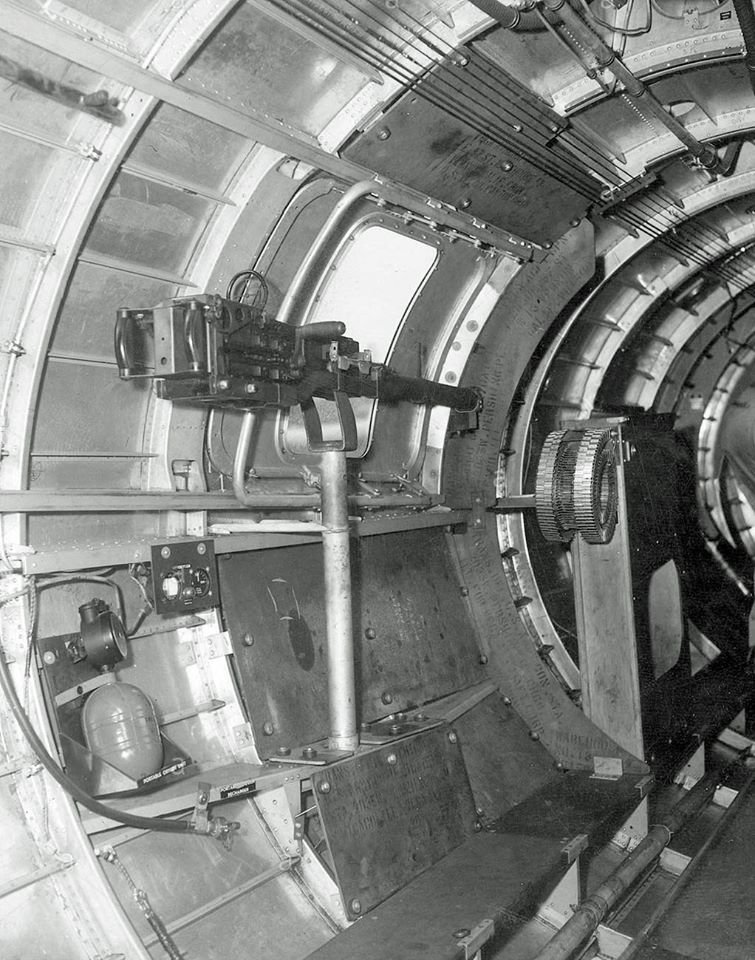

The right waist gun position of a B-17F very similar to Lucky Thirteen.

Note the oxygen panel. The blueprints do not specify whether or not the phenolic for this panel was to be painted, and wartime photographs show both painted and unpainted waist gunner panels.

Based on how the color of the panel seems to match that of the portable oxygen bracket, we elected to paint the waist gunner panels.

Type A-12 Oxygen Regulators donated by Joe McKowen of Gaffney, South Carolina.

Note the difference between the two on the left and the five on the right. The two left ones were made by Aro Equipment and the five on the right by Bendix Pioneer . Additional variants were made by Air Reduction Sales, Johnson Fare Box, and National Die Casting.

While we have an assortment of A-12s in our collection, it is our hope that we can outfit Lucky Thirteen with a full set of Bendix Pioneer type regulators.

The B-17 carried a total of 14 oxygen regulators.

If you can help with this, please let us know!

Hangar Thirteen had a small role in this project.

Jerry Carver of Lexington, South Carolina donated us a Mk. IV bomb release control assembly back in 2020, and since it was not applicable to our project, we saw to it that it went to a good home.

We were proud to see it go toward SBD2-P Dauntless BuNo 2173. The Air Zoo Aerospace & Science Museum restored this aircraft and she has recently arrived at her new home at the Pearl Harbor Aviation Museum.

Congratulations to the PHAM and kudos to the Air Zoo to a job well done. She looks amazing.

An incredible donation:

This bulletproof glass was custom made for us using original blueprints and donated by AGP Plastics of Trumbauersville, Pennsylvania for use aboard Lucky Thirteen.

Simple physics long made clear that most effective defense a bomber could carry was some form of rear-facing armament. As such, when the B-17 was redesigned to carry a tail gun at the beginning of the Second World War, Boeing ensured that said position was the most protected area on the airplane.

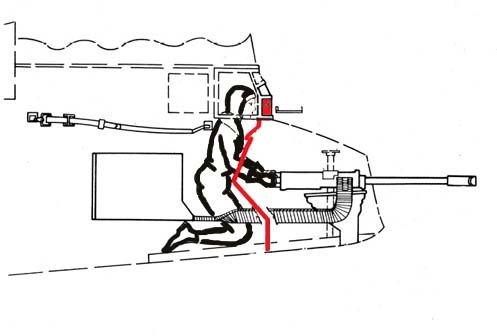

The gunner sat on his knees, supported by an ironing board-like seat which could angle upward. His front was protected by three pieces of 5/16 thick stainless steel armor plate, a full sixteenth thicker than the rest of the airplane’s armor. This protection could be further improved by the airman wearing his flak jacket – a protective garment which sewed overlapping steel plates into a canvas apron. Said jackets were first produced by Wilkinson Sword, known best today as the producer of Schick shaving razors.

The bulletproof glass – or to be more accurate, bullet resistant glass – measured 11 x 7.2 inches, was 2.5 inches thick, and could weigh anywhere between 13 to 18 pounds. Essentially, the glass was made with layers of laminated glass sandwiched between synthetic plastics. To simplify, the glass flattened the bullet on impact and the plastic absorbed its energy, giving the assembly enough flexibility on the microscopic level that it merely cracks instead of shatters.

While it is not uncommon for the bulletproof glass blocks from B-17 stinger tails to pop up on the collector’s market, these glasses tend to suffer from varying degrees of delamination. We did not want to potentially damage one of these original pieces by installing into Lucky Thirteen, however ordering a new glass was not likely to happen, as one online calculator, for example, quoted 1,817 USD to make said piece. So, you can imagine our shock when AGP Plastics stepped forward with this donation. They did a fantastic job with this piece, and we heartily recommend these guys to anyone who might have need of their service!

Surprisingly, there was very little of this material outside the tail gun. Outside the tail, the only bulletproof glass that came standard on the B-17 was the bombardier’s sighting panel, though it was arguably not intended as such. However, it was not uncommon for B-17s to have bulletproof glass installed in their cockpit windscreens once overseas.

The newly-arrived bulletproof glass donated by AGP Plastics for the tail gun on Lucky Thirteen.

Original examples vary in design, with glass layers numbering anywhere between three to five, and finished vs. non-finished edges.

Photo taken 14 July 2022.

SSGT Merlin D. Miller (303BG), peers through the bulletproof glass of a B-17 tail gun position.

Miller was a happy member of the “Goldfish Club,” meaning he survived a blue water ditching. On 6 September 1943 – the day Lucky Thirteen was shot down – Miller’s aircraft, Old Squaw (42-3002, 303BG) ditched in the English Channel, her crew later returning to duty.

Photo taken 6 November 1943.

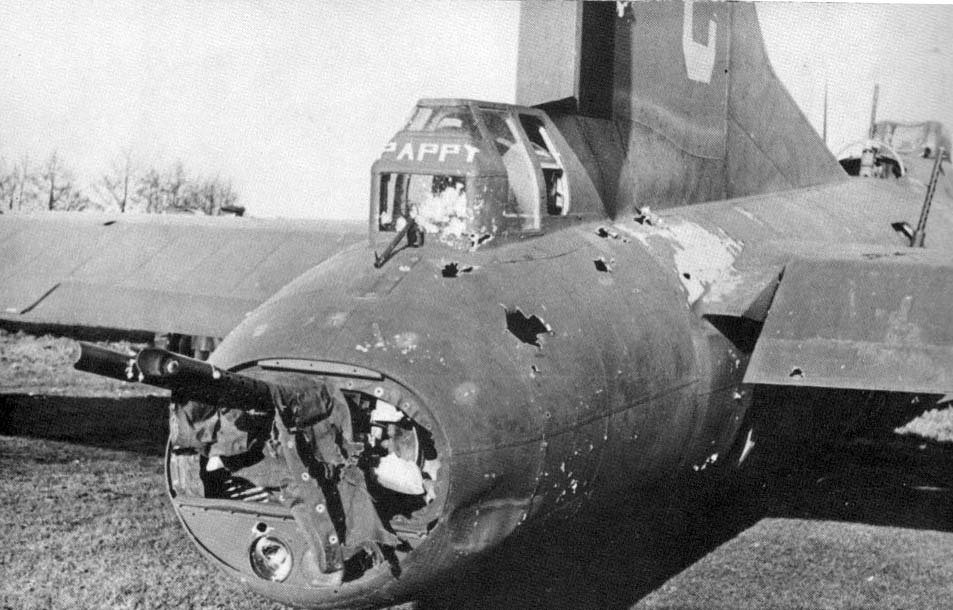

‘C-for-Charlie’ (42-37787, 379BG), shot down near Borger, in the Netherlands, on 26 November 1943. All ten of her crew survived the crash and were taken prisoner.

Note the impacts on the bulletproof glass – if it weren’t for that glass, it is quite likely that tail gunner SSGT Francis A. Svehla would have been killed.

A graphic illustration of the tail gunner’s protective pieces. The three armor plates, as well as the bulletproof glass, are drawn in red.

E and early F-model B-17s had additional tail armor plates which attached to the fuselage sides.

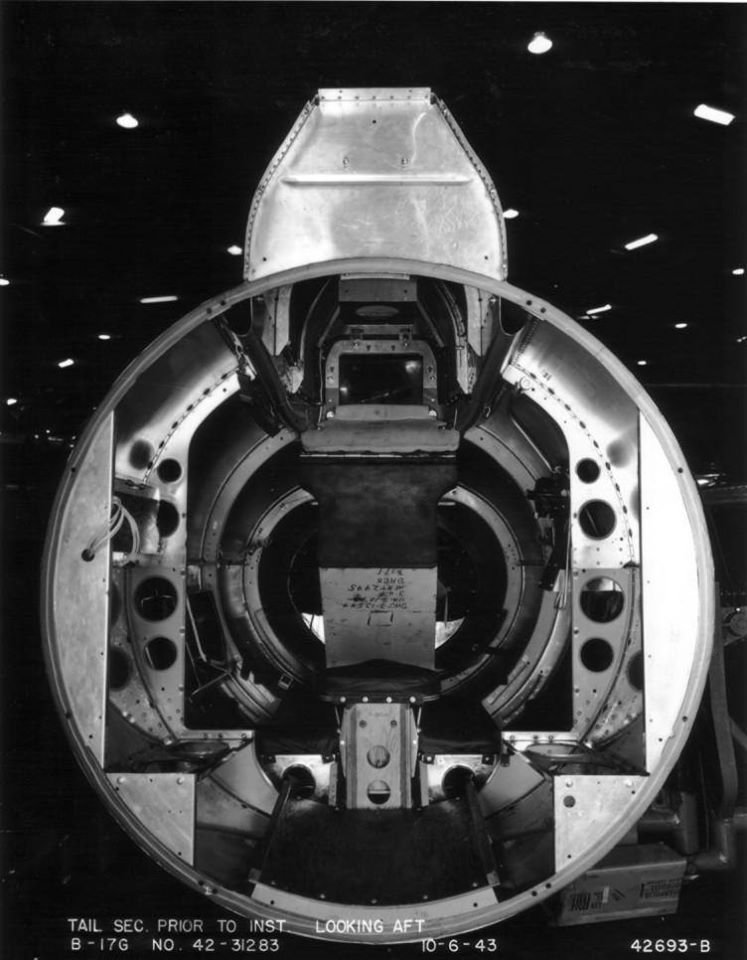

The tail gun position of 42-31283, a B-17 that never left the states. The ammo boxes have not been installed yet, though you can see where they would later be located. The gunner sits on the bicycle seat, his knees on the padding and his chest against the armor plate.

Photo taken 10 June 1943.

CO 743BS MAJ David G. Bellemere stands in front of Tepee Time Gal (41-29583, 455BG), a Consolidated B-24H with the 15AF in Italy.

A rare photo showing a USAAF airman wearing his full kit, Bellemere is wearing a steel-plate lined flak jacket.

Note his boots – they are RAF issue. RAF boots were highly prized by USAAF personnel.

The bulletproof glass donated by AGP Plastics is unpacked.

The packaging was superb, the glass being wrapped in layers of cardboard, in a nailed-shut wooden box (hence the hammer), then again wrapped in cardboard.

Photo taken 14 July 2022.

Toonces the Cat peeks through the newly-arrived bulletproof glass.

A nice indicator of just how clear it is despite being 2.5 inches thick!

Photo taken 14 July 2022.

An employee of Boeing’s Renton, Washington plant installs bulletproof glass into the tail position of a Boeing B-29.

The first tail gun – the Sikorsky Ilya Muromets. This aircraft also has the distinction of being history’s first four-engine heavy bomber.

The aircraft’s designer, Igor Sikorsky, was a devout Christian and somewhat wealthy by period standards. As such, he fled Russia during the Communist takeover and became a US citizen. Today, he is best known as the father of the helicopter.

Notably featured in the William Wyler documentary Memphis Belle, Old Bill (42-29673, 305BG) was severely damaged by a FW-190 on 15 May 1943 over Wangerooge, Germany.

The bombardier and pilots were severely wounded and navigator 2LT Doug R. Venable, Jr. was killed. Despite his wounds, bombardier 1LT Bob W. Barrall nevertheless managed to fly Old Bill back home.

Note the bombardier’s viewing window remains, even though the plexiglass nose cone has been blown away. While layered like bulletproof glass, the main purpose of this window was to provide a clear, undistorted view for the bombsight.

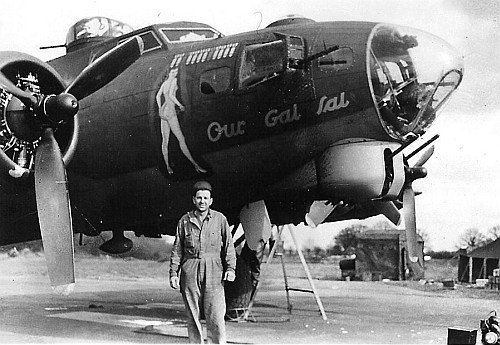

My Gal Sal (42-31767, 100BG) serves as a handy before/after reference on bulletproof glass installed in the B-17 cockpits.

My Gal Sal was the sole surviving 100BG aircraft on the 6 March 1944 strike against Berlin (the first US attack against the German capital).

One of the more recognizable B-17s of the war, Little Miss Mischief (42-97880, 91BG), after crashlanding on 15 October 1944 following a strike on Cologne, Germany. Anti-aircraft fire did this to the waist section, wounding waist gunner SSGT Glenn Slaughter and ball turret gunner SSGT Ed Adbo.

Note the damage to the center glass on the ball.

While the ball turret manual refers to this as “safety glass,” it is clear from this photo (and photos of other damaged ball turrets) that it was not bullet-resistant type glass.

Our friend Stijn Claus over at the B-17 Flying Fortress Parts Project has recently made a post concerning Lucky Thirteen that I think everyone might enjoy:

Our project is closely affiliated with the the Hangar Thirteen project. So if we can help each other, we do. Lucky Thirteen needed all three seat and back covers for their project, so these were made for them. The seat covers were patterned from original canvas covers, which are close, but not exactly the same. With the help from Gerad, and the info provided on the Hangar Thirteen website, we were able to fabricate these, including the particular attachment system used in these Cramer posture chairs.

All that is left to do is source and install the correct press studs for the back covers.

Stijn is referring to the Cramer Air Flow series posture chairs that were installed in the bombardier, navigator, and radio operator positions aboard the Boeing B-17.

Check out his phenomenal work!

The Cramer seat cushions made by Stijn for Lucky Thirteen.

These were made using a combination of references: a Boeing B-29 Cramer chair, the untouched radio operator’s chair aboard the B-17G Mary Alice (44-83735) on display at the Imperial War Museum in Duxford, England, a set of instructions hand-written for Hangar Thirteen by a wartime Cramer employee, and an original cushion in the Hangar Thirteen collection.

Photo taken 15 July 2022.

The Cramer seat back pads made by Stijn for Lucky Thirteen.

Stijn is currently looking for United Carr or Rau type snap fasteners for these pieces.

Photo taken 12 July 2022.

The navigator’s position aboard Flak Dodger (42-29467, 99BG) – a typical arrangement on a B-17F. Note how the backrest on the chair has been mounted inverted so the navigator can waddle on and off his seat.

Earlier Fs had bucket seats for the bombardier and radio operator’s positions. The bombardier’s bucket seat was not popular and many early F-models flew without a seat for his position.

A screenshot taken from William Wyler’s documentary Memphis Belle (1944) shows CPT Chuck B. Leighton and CPT Vince B. Evans in the nose of Memphis Belle (41-24485, 91BG).

The bombardier’s factory-installed bucket seat has been removed, leaving this area bare (no posture chair either). Note that these airmen would not have been able to pose at this angle had a chair been installed in the bomber’s nose.

The bombardier aboard a late-F model B-17 – virtually identical to Lucky Thirteen – poses for the camera.

Note the Cramer posture chair.

The radar operator’s position aboard a B-17G pathfinder. B-17 pathfinders generally replaced the ball turret position with the radar assembly, the radar operator sitting opposite the radio operator with his equipment mounted in front of the command radios.

Note the Cramer posture chair. Most surviving wartime Cramers today are off of B-29s. B-29 chairs had three legs and were upholstered in canvas. B-17 chairs had four legs and were upholstered in bronze green vinyl.

My first project working on Lucky Thirteen. Ray asked if I could replicate the original Cramer seat plate (right).

Now that Stijn has made the cushions, I guess we need to get to rebuilding the seatframes!

One of our current projects is the rebuilding of the aircraft’s instrument panels, starting with the primary cockpit panel. This is one of the areas that distinguishes F-model B-17s like Lucky Thirteen apart from B-17Gs. Instead of wooden housings, which were typical of B-17Gs, B-17Fs had aluminum panel housings. While Bob Hachmann has been working to fabricate this housing, we have cut a wooden mock-up of the panel, using it as a placeholder while we track down the necessary gauges.

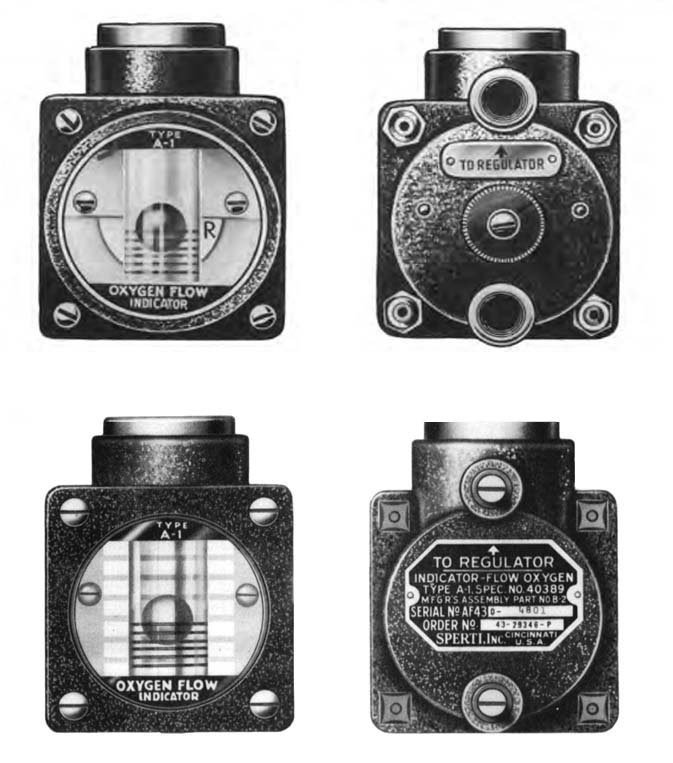

Of course, there are more gauges than just what goes in the cockpit. The most common gauges aboard the B-17 are the oxygen gauges, and a special thanks is due to our friend Steve Hester of Falls City, Texas for donating a large number of Type A-1 Oxygen Flow and Type K-1 Oxygen Pressure gauges.

The Type A-1 is a particularly hard-to-find unit, as it was unique to mid-war US aircraft.

The first B-17s equipped with demand-flow oxygen systems (as opposed to constant-flow oxygen systems) entered combat in April 1943. The A-1 looked like a carpenter’s level, the cork inside giving a visual indicator of the airman’s breathing. This fact is rather important to Lucky Thirteen. On 17 August 1943 (the infamous Schweinfurt-Regensburg strike), waist gunners SSGT John F. Schimenek and SSGT L. Corwin Miller were seriously wounded by a 20mm cannon shell which hit Lucky Thirteen. Miller suffered a punctured lung and Schimenek’s account notes that he ‘watched the cork’ to ensure that Miller was still breathing. This could only be done with an A-1 Oxygen Flow gauge.

The A-1 was the product of the Sperti Corporation of Cincinnati, Ohio and contained a twistable background behind the level, with one half always being obscured by a fluorescent top plate. This gave the user the option to select between a totally fluorescent background, or a half-fluorescent/half-phosphorescent background. Toward the end of its life, the A-1 was redesigned to remove the fluorescent components, the background being little more than a series of radioactive-phosphorescent strips. However by October 1943, the A-1 was phased out completely, being replaced by the Type A-3 Oxygen Blinker. The A-3 stayed in service long after the war and, due to its simple design and relative accessibility, remains common on warbirds today.

Because the A-1 was only in service for about a year, any A-1 gauge is a welcome find. Many of the A-1s that Steve located were in rough shape. As such, I had to partially disassemble each unit and perform a series of minor restorations. Particularly helpful was the hot South Carolina sun, which was used to bake wrinkle paint onto those gauges that needed it. We are quite pleased with how they turned out and hope you feel the same way!

Thanks to Steve for contributing these rare gauges. In fact, Steve’s donation allowed us to meet the goal of having a full complement of early-style K-1 Oxygen Pressure Gauges. Kudos!

Another rare contribution comes from Rande Jaffe of Brier, Washington. We were able to purchase from Rande the 0-40 AC ammeter that was located on the pilot’s side of the instrument panel. We were fortunate that Rande had examples with phosphorescent markings (accurate to our project), and Rande was kind enough to sell us the gauge at cost, as well as donate a second gauge to keep as a backup. Thanks Rande!

Two A-1 Oxygen Flow gauges, with their cosmetic restorations complete.

Photo taken 24 June 2022.

The A-1 gauges when Steve found them.

Photo taken 27 April 2022.

The cockpit of a B-17F slightly older than Lucky Thirteen.

The oxygen flow and pressure indicators were on the pilot’s side, below the navigation repeater instruments. The copilot’s oxygen gauges are highlighted here. The pilot’s oxygen gauges are obscured by the control column.

Unlike most gauges, the glass in the A-1 is actually clear acrylic. Fortunately, this made it easier to create new ‘glass’ for those that were missing their faces.

The newly cut acrylic faces are above, while a pair of originals are below.

Photo taken 7 May 2022.

Freshly cleaned and repainted (where needed), the markings are reapplied to this Type A-1 Oxygen Flow gauge.

Photo taken 24 June 2022.

Manual illustrations showing the difference between early and late-variant A-1 Oxygen Flow gauges.

The bottom type was only in service for a short period before being replaced by the Type A-3.

The navigator’s position on Chatterbox II (42-102955, 351BG), a G-model B-17.

Note the oxygen panel directly in front of the navigator’s table. While it still uses the early-variant K-1 Oxygen Pressure gauge, the oxygen flow indicator is an A-3 Blinker type.

As an interesting aside, note how the wood on the oxygen panel has not been painted. This is because the nose compartment is not insulated. If it was an older B-17 with an insulated nose compartment, the wood would have been painted bronze green and the phenolic black.

Photo taken 20 April 1944.

Steve’s newly donated Type K-1 Oxygen Pressure gauges. These too required minor cosmetic restoration. But combining them with those donated by Joe McKowen (Gaffney, South Carolina), we now have a full complement of pressure gauges.

The two panels in the back are the oxygen panels for the waist gun positions aboard Lucky Thirteen, awaiting their markings.

Photo taken 11 July 2022.

A handy photo to demonstrate the difference between early and late variant K-1 Oxygen Pressure gauges.

The three above are late-war variants and were most common on postwar aircraft.

The silver device on the right is a cat toy with a UV light option – essential for checking gauges!

Photo taken 25 April 2022.

Rande’s newly arrived 0-40 AC ammeters.

Photo taken 24 June 2022.

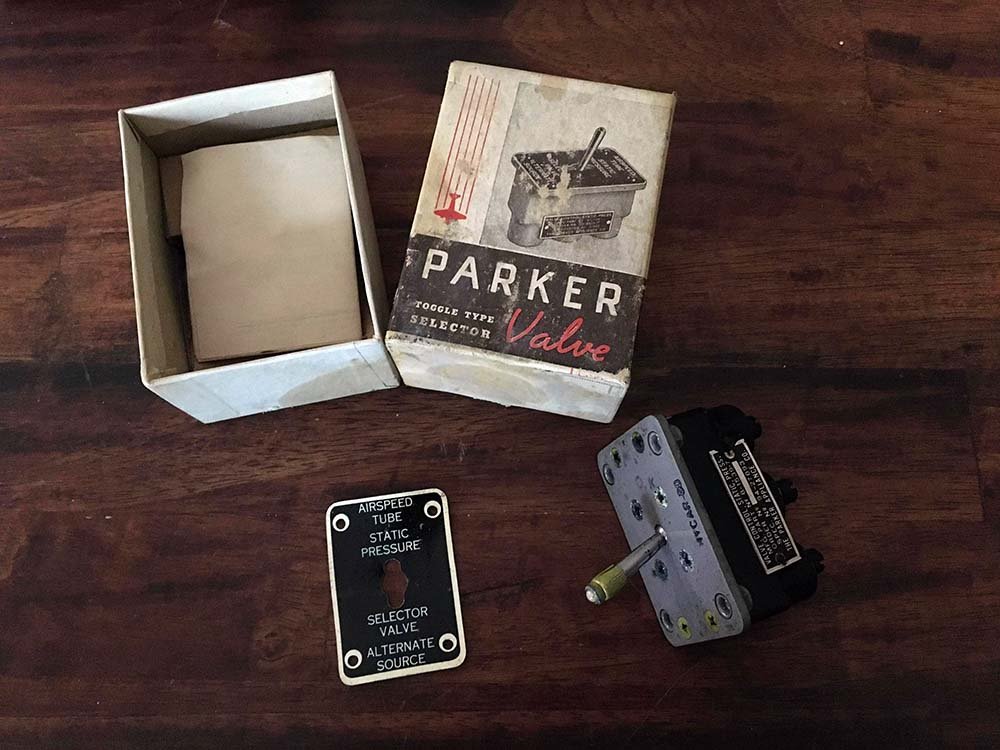

Joe McKowen donated a pair of AN5831-1 Static Valve Pressure Switches, still in their original boxes.

Surprisingly, the face plates for these were made of cardstock, and with age, had shrunk to the point that they could no longer be mounted.

Photo taken 28 May 2022.

Our recreation of the cardstock faceplate for the AN5831-1 Static Pressure Valve switch.

Photo taken 28 May 2022.

The AN5831-1 installed with its new faceplate.

We recently learned that Lucky Thirteen was one of the first B-17s without the ceiling mounted emergency brake. We have contacted Boeing historian Mike Lombardi to confirm our findings. But if it turns out to be true, not only must we lose a hydraulic pressure gauge, but we must replace the two jeweled lights above with a pair of red dimmer lights.

Photo taken 28 May 2022.