This booklet consisted of interviews with the crew of Memphis Belle (41-24485, 91BG), the first Boeing B-17 crew in the US Eighth Air Force to survive a combat tour of 25 missions and return to the United States. The booklet was issued to bomber crews as a means to advise them before going overseas.

Memphis Belle is currently on displayed at the National Museum of the US Air Force in Dayton, Ohio.

Special thanks to Paul Teal for providing images of an original example so this transcription could be made.

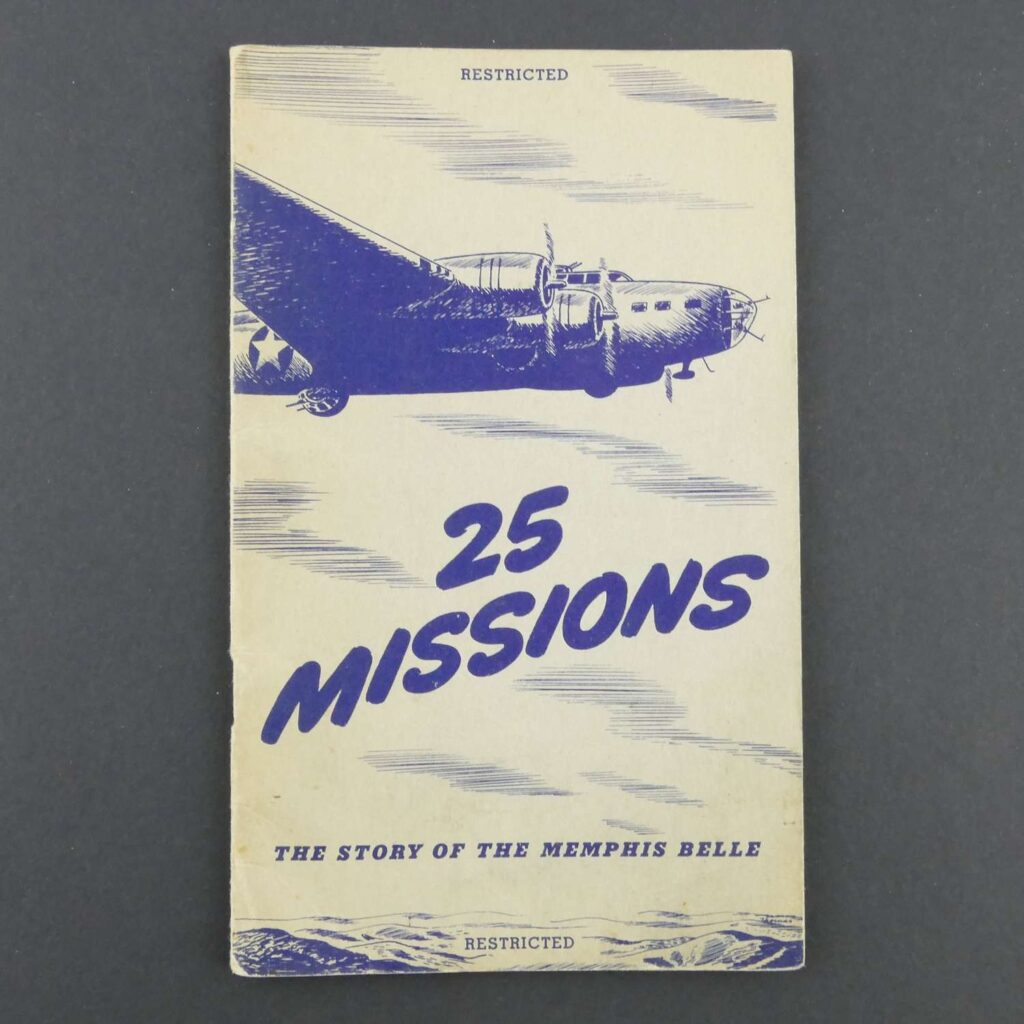

25 Missions: The Story of the Memphis Belle

25 Missions: The Story of the Memphis Belle

Published by the authority of the Commanding General, Army Air Forces

Training Aids Division

Army Air Forces

Park Avenue and 32nd Street

New York City

July, 1943

FOREWORD

THE “Memphis Belle,” a Boeing B-17, has been retired from active service in the European theater after 25 successful bombing missions. With its distinguished crew, which has remained intact since its formation 10 months ago, the ship has been returned to the United States for another — and no less important — mission.

At my direction, Captain Robert K Morgan, the pilot, his crew and his ship are making a tour of Army Air Forces training establishments in all parts of the United States. There are three principal reasons for this tour.

First, that combat crews in those units now being trained for the European theater may be guided in their training to achieve combat skill, teamwork, mutual confidence and fighting spirit.

Second, that student pilots, bombardiers, navigators and gunners may profit by the experience and knowledge of the men of the Memphis Belle.

Third, that battle conditions now existing in Europe and the magnificent achievements of the United States Eighth Air Force in mastering these conditions may be represented properly to AAF personnel and the public.

I consider it important that the messages of these men be given maximum circulation. Therefore, I have had each member of the crew interviewed by

2

an officer of the Army Air Forces and their stories, told in their own words, published in this booklet.

I commend the contents of this booklet to the thoughtful reading of all AAF personnel and especially those officers and enlisted men being prepared for duty in the European theater.

Here are factual accounts of aerial warfare over Germany and the occupied countries. Here is an appraisal of the enemy we are fighting. Here is the advice of men who have taken the war to the enemy. We must not fail to make the most of the experience of men who have pioneered the American task in Europe.

H. H. Arnold

Commanding General

Army Air Forces

3

THE MEMPHIS BELLE…

IN September, 1942, a new Flying Fortress was delivered at Bangor, Maine, to crew of ten eager American lads headed by Robert K. Morgan, a lanky 24-year-old AAF pilot from Asheville, N.C.

Proudly, the boys climbed aboard, flew their ship to Memphis, Tenn., christened her “Memphis Belle” in honor of Morgan’s fiancée, Miss Margaret Polk of Memphis, and then headed across the Atlantic to join the U. S. Eighth Air Force in England.

Morgan had told them it was rough where they were going. There would be no room in the Memphis Belle for fellows who couldn’t take it. The boys said they were ready.

They took it. Between November 7 and May 17, they flew the Memphis Belle over Hitler’s Europe twenty-five times. Bombardier Vincent B. Evans dropped more than 60 tons of bombs on targets in Germany, France and Belgium. They blasted the Focke-Wulf plant at Bremen, locks at St. Nazaire and Brest, docks and shipbuilding installations at Wilhelmshaven, railway yards at Rouen, submarine pens and power houses at Lorient, and airplane works at Antwerp. They shot down eight enemy fighters, probably got five others, and damaged at least a dozen.

The Memphis Belle flew through all the flak that Hitler could send up to them. She slugged it out

4

with Goering’s Messerschmitts and Focke-Wulfs. She was riddled by machine gun and cannon fire. Once she returned to base with most of her tail shot away. German guns destroyed a wing and five engines. Her fuselage was shot to pieces. But the Memphis Belle kept going back.

The longest period she was out of commission at any one time was five days, when transportation difficulties delayed a wing change. When the tail was destroyed the Air Service Command had her ready to go again in two days.

Only one member of the crew received an injury. And that, says Staff Sergeant John P. Quinlan, the victim, “was just a pin scratch on the leg.”

The Memphis Belle crew has been decorated 51 times. Each of the 10 has received the Distinguished Flying Cross, the Air Medal and three Oak Leaf Clusters. The 51st award was Sergeant Quinlan’s Purple Heart.

The ship’s 25 missions follow:

November 7… Brest, France

November 9… St. Nazaire, France

November 17… St. Nazaire

December 6… Lille, France

December 20… Rommily-Sur-Seine, France

January 3… St. Nazaire

5

January 13… Lille

January 23… Lorient, France

February 4… Emden, Germany

February 14… Hamm, Germany

February 16… St. Nazaire

February 26… Wilhelmshaven, Germany

February 27… Brest

March 6… Lorient

March 12… Rouen, France

March 13… Abbeville, France

March 22… Wilhelmshaven

March 28… Rouen

April 5… Antwerp, Belgium

April 16… Lorient

April 17… Bremen, Germany

May 1… St. Nazaire

May 4… Antwerp

May 15… Wilhelmshaven

May 17… Lorient

The flight time on these missions ranged from three hours and 50 minutes on December 6 to nine hours and 30 minutes on May 1. The total sortie time for the 25 missions was 148 hours and 50 minutes. Approximately 20,000 combat miles were flown.

Today, the battle-scarred Memphis Belle is back home with her remarkable crew, the same crew to a man that was organized 10 months ago in Maine. The Belle is the first bomber to be retired from active service and flown back from the Eighth Air Force.

6

Still flying the Memphis Belle, the crew is touring the United States to tell their story to the boys in training establishments. Student bomber pilots, navigators, bombardiers and gunners are learning from the members of this crew the things they picked up the hard way.

The succeeding pages of this booklet tell the stories, in their own words, of the boys of the Memphis Belle. Here is what they saw, learned and did in the world’s toughest theater of aerial combat. There are important lessons in these stories. Let us learn and apply them.

7

CAPTAIN ROBERT K. MORGAN

Pilot

He is the officer in charge of the ship and is called ”chief” by his crewmen, who swear by him, declare he is the best in the business. Typical is the observation of Sergeant Quinlan, “Thousands of times I have seen him make that ship do the impossible.” Morgan is 24, tall, competent, comes from Asheville, N. C., was an industrial engineer before going in the Army in April, 1941.

HIS STORY

IF you want in just one word how we were able to go through the hell of Europe 25 times and get back home without a casualty, I’ll give it to you. The word is TEAMWORK. Until you have been over there, you can’t know how essential that is. We had 10 men working together, each ready and able to help out anybody else who might need him.

Take just one example of what I am talking about. If it weren’t for the tail gunner using the interphone to keep me posted on the formation behind, the top gunner reporting to me what he can see, the ball turret gunner telling me what he can see, it would be almost impossible for me to fly the airplane in combat. I can’t get up and look around. Those fellows are my eyes.

In the same connection, every man in a bomber crew should know something about every other man’s job. Aside from the value of having someone to take over in case of emergency, understanding the other jobs and knowing each other’s problems develops teamwork. It also promotes confi-

8

dence in each other and enables us to anticipate each other’s needs for help.

I would like to make one suggestion to improve the training of bomber pilots. Cut down on transition training — landings and take-offs — and emphasize high altitude flying and formation flying. I could have used a lot more of that.

Now a few tips:

Before taking off on a mission, the pilot should check the airplane over from one end to the other. I mean that literally. He should check even the smallest details and never be satisfied with anybody else’s word that everything is okeh.

He should consult with the navigator and get the course well in mind so that he can anticipate turns, can have some idea where the heaviest flak is going to be, etc.

Heavy flying equipment is cumbersome, and a bomber pilot doesn’t need it. It never gets very cold in the cockpit, and anyway the pilot is so busy he could sweat at 35 below. I wear heavy underwear, a regular uniform and coveralls, and that’s enough.

Keep your formation. I can’t emphasize that too strongly. At first the idea seemed to be to get the bombs out and then go hell-bent for home. But we have learned how important it is that the formation be maintained. There have been cases when we turned a formation nearly around to pick up a man who was straggling.

The Germans always try to break up the formation and then jump the stragglers. If we concentrate our fire power by keeping the formation, the only

9

thing they can do is to slug it out with us. They don’t like that.

WE like having fighter escort. We wanted P-38’s but couldn’t get them. The best escort we ever had was the P-47. If they’ll give us fighter protection, they’ll get a lot of stragglers back home that otherwise won’t make it.

As for German tricks, here’s one to watch for: they are painting Focke-Wulfs with white stripes like our P-47’s. It’s hard to tell them apart at a distance. Also, the Germans have a camouflage color that is very effective when they get up in the sun. If you aren’t careful, you won’t see them and they’ll be on you before you know it.

The Germans are learning some things about the Americans. They used to say that we couldn’t carry out daylight raids over Europe because our losses would be too great. They also said we couldn’t hit pinpoint targets. We have proved them wrong on both counts.

American morale in England is good, and is getting better every day. Morale is always good when results are good. Also, we were well provided for, and the British were damned nice to us.

THERE are many incidents that I could tell you about, but here is one that stands out most vividly in my memory.

On January 23, our mission was a raid on the submarine installations at Lorient. One of the other groups went over the target first. Through the flak,

10

fighters were beginning to attack us. Because ours was the smallest of the four groups, they concentrated on us, and for about 22 minutes they gave us hell.

Most of the attacks were from the front. One Focke-Wulf 190, attacking straight in from 12 o’clock, was heading right into us. One of us would have to move. The usual procedure would be to dive. I couldn’t do that, because another group was below us, so I pulled her straight up. The shells that were intended for our nose got our tail.

I didn’t know what had happened until Sergeant Quinlan started giving it to me play by play.

“Chief, the tail is hit, the whole back end is shot off!” I heard him say. “Chief, it’s blazing! The whole tail is leaving the plane!”

There was a silence then. I asked for a report. Nothing happened.

Finally, I heard Quinlan’s voice again, “Chief, it’s still on fire! There goes another piece!”

Another silence for a minute, and then Quinlan said, “Chief, the fire has gone out.” I don’t need to tell you that that was the sweetest music I have ever heard.

I climbed up to look back and see what had happened. It looked like we had no tail at all. I got back in the cockpit and flew for two hours back to the base. It was tough flying, and tougher than that to set her down. The elevators were damaged so badly that the controls jammed.

But somehow we managed to get down safely. That was a close call.

11

CAPTAIN JAMES A. VERINIS

Co-Pilot

Captain Verinis went over with the Memphis Belle as co-pilot, but during much of the time he was overseas he flew another B-17 as first pilot. Captain Morgan leans heavily on him, insists that he be called the “other pilot,” not co-pilot. He is 25, short, dark, soft-spoken, comes from New Haven, Conn., was a business administration student at the University of Connecticut before entering the service in July, 1941.

HIS STORY

TO begin with, let me say to the fellows who go over as co-pilots that they probably won’t be co-pilots long. The chances are that if they are good they will get their own ships. So don’t get the idea that you are going to fight the war as a co-pilot. You should be prepared to take over your own ship and crew any minute you are called upon to do so.

But while you are co-pilot, you have very definite responsibilities. Captain Morgan and I had it pretty well worked out. As co-pilot, you should do everything you possibly can do to relieve the pilot. The pilot has tremendous responsibilities, and I consider it the co-pilot’s job to relieve him of all the worries that he can.

There is no question about the need for a co-pilot in the B-17. The strength of one man is not sufficient to kick it around in combat. Usually, the co-pilot will do at least half the flying, but the pilot takes over in actual combat.

12

But even in combat, when the pilot is flying the ship, the co-pilot should keep his hands on the wheel and his feet on the rudders in that way he is ready, when needed, to apply pressure in the direction the pilot indicates.

If the co-pilot sees something that the pilot doesn’t or can’t see, he should notify the pilot or take the controls himself. It has been my observation that there is too much of a tendency to leave everything to the pilot. It’s too much for one man. He can’t see everything, and the co-pilot should help him watch.

I consider the training I had fairly thorough, but I did need more high altitude and formation flying. There is too much transition flying. There are fellows coming over with 500 to 600 hours in the B-17. A lot of that is wasted. After completing my tour, I have only about 450 hours.

If you are going over, talk to somebody who has had combat experience. The fellows who have been through it can tell you a lot about dodging fighters.

Here’s something else important: learn to judge exactly when you are in position to be hit. And don’t forget that pursuit planes have fixed guns and they’ve got to be pointed at you before they can hit you. You don’t have to run all over the sky to dodge them if you’ll just learn the positions that keep you out of their aim.

The Germans have some tricks they use on us, but they are all perfectly obvious if you keep on

13

the alert. For instance, they will pretend to be shot down. They will shoot out a Jet of black smoke and peel off. But if you watch you’ll see them come right back. They seldom fool anybody.

THE worst scare I ever had was in a raid on Hamm March 3. I was flying my own plane that day. There were 16 planes in our formation and we ran into about 100 fighters. We were caught 150 miles inland. We came out of a haze and discovered that our 16 planes were alone, because all our others had gone to the secondary target.

They got four of the 16, and I want to tell you that we were lucky to get back with 12. It was a running fight for an hour and 20 minutes. They literally swarmed on us just after we dropped our bombs. They were down and up, side and over. Boy, it was a sight.

NOW that the boys know they have only 25 raids to go before they get a let-up, morale is good. As long as they have a goal, as long as they know there is a stopping place, they’re okeh. If they felt they had to go on indefinitely, the spirit wouldn’t be so good.

Don’t misunderstand me. It’s no picnic over there. If anything, the missions are getting tougher. These daylight raids on the Ruhr valley must be hell. I’ve never been over the Ruhr myself.

But the boys know that their equipment is good. They know that our bombers surpass anything that anybody else has. Our P-47 will tangle with

14

a Focke-Wulf any day. And our pilots and crews are good.

Here’s another thing that helps the spirit of the boys: the food and housing are excellent, and conditions generally outside combat are better than in any other theater. There is no danger at the base. The tension is off when you get back from a mission.

Just keep sending the B-17’s over there, and our boys will be all right.

15

CAPTAIN VINCENT B. EVANS

Bombardier

A genial Texan, 23 years old, one of the two married members of the crew. From five miles up in the substratosphere precision bombing is a fine art. The Eighth Air Force knows him as one of the best. Before going in the Army in January, 1942, he operated a fleet of trucks in Fort Worth.

HIS STORY

AMERICAN bombing skill and equipment are the best the world has ever seen. There is no question about that. They all marvel at the results we get from high altitude bombing. And I am convinced that the German war machine will be destroyed by daylight, precision bombing from high altitudes.

When you go after one specific small target – not a whole plant, but one building in a plant — find your target, and put your bombs right on it, you are doing some real bombing. There’s no guesswork about it. And that’s what the Americans are doing day after day.

As for my job as bombardier, I wouldn’t trade with anybody. Of course, I would like to be a pilot too, but if I had it to do over again I would sign up for bombardier training. It’s the greatest thrill in the world to see your bombs hit the target.

I would like to see our schools place more emphasis on high altitude bombing training. Also, our training should concentrate more on pilot-

16

bombardier teams, teaching them to work together, and less on individual training. Bombing problems should be given —real problems, like bombing Denver from Seattle. That would be a great help to the boys in preparing them for combat.

Student bombardiers should be given more practice in photographic and map reading. I didn’t get any of that in school. They should be given more pilotage navigation training. Every member of a B-17 crew should learn other duties besides his own. The four officers should be able to interchange.

A fellow who doesn’t finish near the top of his class shouldn’t get discouraged. The fact that a man leads his class in school doesn’t mean that he will be the best bombardier or pilot. You just can’t tell until you try him in combat.

(At this point Captain Evans was asked to relate his experience in the St. Nazaire raid of January 3. For that performance he was awarded the Air Medal.)

It was a building that we were after that day. It was a small target, but very important and we were glad of the opportunity to lead the Eighth Bomber Command. As we turned to make a run on the target, which I knew by its relation to other buildings, we ran into a strong wind which we hadn’t anticipated. That caused the plane to go wide on the initial point and also caused our ground speed to drop to 85 or 90 miles an hour. There we were sitting up there like clay pigeons.

17

THE CREW:

Left to right: standing, Technical Sergeants Hanson and Loch, Captains Evans, Leighton, Verinis and Morgan, kneeling, Staff Sergeants Scott, Winchell, Quinlan, and Nastal.

I told Captain Morgan and Colonel Putnam (Lieutenant Colonel C. E. Putnam, also of Fort Worth, who was riding as co-pilot and wing leader), that it was going to be a long run. They said let’s settle down on it. We were anxious to get it right.

We had a 2 1/2-minute run. The usual one is about 55 seconds. We were really sweating out the last few seconds of that run. The flak was terrific I could see the flashes of the antiaircraft fire through my bombsight and occasionally a fighter crossing underneath I could hear flak slapping the side of the ship like kicking the door of a model-T Ford. Later we discovered that we had a lot of holes in the ship, and a tire was blown to hell.

Captain Morgan asked me when the hell I was going to drop the bombs. I told him to take it easy. I put my crosshairs where I knew the target to be, although I couldn’t make it out at that distance. The second I released the bombs, I knew they were going to be good. The bombardier can usually tell. They were squarely on the target.

(Captain Evans put it modestly. Actually, photographs showed that the mean point of impact was only 10 or 15 feet off the center of the target, a torpedo shed.)

THE new Automatic Flight Control Equipment will be a means of shortening the bombing run. When we went over, they hadn’t perfected AFCE. Bob (Captain Morgan) and I worked so well together that we were able to do all right manually.

20

Now that AFCE has been perfected, I certainly would recommend it to other crews. We have tried it and found it to work very well.

Here’s a tip that will help: When you first turn on the target, take out the big corrections by talking the pilot over, using the interphone, before clutching in. Then you will have only minor corrections to make.

Bombardiers would do well to spend a lot of time in the bombsight vault talking to enlisted men. I figure that I have learned 30 percent of my knowledge of the bombsight from commissioned officers, 30 per cent train actual experience, and 40 per cent from enlisted men in the bombsight vault. These master sergeants can really put you wise to a lot of things.

I believe in dropping on the leader. It is the only way to keep the formation closed for maximum fire power. Of course, it puts the monkey on the lead bombardier’s back. It makes me nervous to think about it.

21

CAPTAIN CHARLES B. LEIGHTON

Navigator

Quiet, likeable Captain Leighton has never been lost in European skies, tough as long-range navigation as in aerial combat. He calls it luck. His fellows on the Memphis Belle credit it to skill and alertness. Declared Sergeant Hanson, “He has never made a mistake.” He is 24 years old, comes from East Lansing, Mich., was a chemistry student at Ohio Wesleyan before entering the Army January 20, 1942.

HIS STORY

WE usually have three hours between the briefing and the take-off. During that time the navigator is busy as hell. He must make sure that he fully understands weather conditions, including any anticipated changes. He must check on any flak areas on or anywhere near the route so that he can avoid them. He must be thoroughly familiar with the formation that is going on the mission.

After briefing, he consults with the pilot. In fact, it is a very good idea to go over the route with the pilot and the whole crew before take-off. Otherwise, some of them won’t be able to keep up with where they are, and that is a great handicap.

It is especially important for the navigator to talk to the radio operator and to make sure that all the radio equipment is ready.

I think the navigator should brief the pilot on how to get back in the event something happens to the navigator. I have tried drawing the route on a small map for the pilot. I think it’s a good idea, but every precaution should be taken not to let a

22

map get out and it must be destroyed if the ship goes down.

I SHOULD have had more gunnery training. The first moving target I fired at was a Focke-Wulf.

I could have used more practice in navigation. It would be good training to take a navigation student up, let him play checkers or something for a few minutes, and then have him try to figure out where he is. Without practice of that kind, you might have a hard time finding yourself after a fight.

There are two conditions that might cause a navigator trouble.

First, poor weather when he can’t see the ground.

Second, a fight that takes him out to sea, causing him to lose all his landmarks.

This leads me to this important advice: Train yourself to write down your compass heading and to continue your navigation work even through a stiff fight.

I like being a navigator. Of course, I would like to get up and walk around a little sometimes, but I can’t. I have to work like the devil all the time. But there is nothing like the satisfaction a navigator gets when he hits his ETA (estimated time of arrival) right on the head.

When you are the lead navigator, the whole formation depends upon you. The responsibility is frightening sometimes. It really keeps you on the ball. Actually, though, you should be just as

23

alert if you are the navigator of any of the other ships in the formation. You might lose your lead ship or you might get separated from the formation.

There are some things to watch for. The Germans will sometimes send out beams exactly like ours to throw you off. Once some of our ships were fooled by these false beams, and the Germans brought them over Brest, which looks like the English coast. Then German fighters dropped on them and got three of our planes.

Another German trick is to stay just out of range and play around, trying to get us to use up our ammunition.

You get scared sometimes, but usually any feeling of fright or tenseness leaves you when you start mixing it up. The worst scare I ever had, I think, was in our second mission over St. Nazaire. We were at 10,000 feet. Looking out the window all the way down the run I could see the bursts following us, one after another. It was only a minute or so, but it seemed like 15 years. When we heard “bombs away,” we ducked. It wasn’t a second too soon.

From experiences like that, I have learned that it is important to keep your eyes off the flak. It helps a lot. I also got scared the time I ran out of ammunition. We were away down past Paris. It doesn’t bother me if I can shoot back. But looking down those barrels and not having anything to shoot is no fun.

24

TECHNICAL SGT. HAROLD P. LOCH

Engineer and Top Turret Gunner

Having slugged it out with Hitler’s fighters from a B-17 top turret, he now wants to be a fighter pilot. Sergeant Loch is 23 years old, comes from Green Bay, Wis., used to be a stevedore, has been in the Army since November, 1941

HIS STORY

THE engineer of a B-17 doesn’t have much ground work. I think he should have more, at least enough to keep his hand in. It is important that he know his engines, that he know every gauge, switch and fuse. Fuses are especially important to him, because they sometimes blow out and he must know where they are.

Every man on the B-17 should be able to assemble his gun blindfolded. He ought to be able to fix it quickly if it goes out while he is in the air.

The biggest part of the attacks come from the nose. German fighters will come from away behind, slip up to the side just out of range, and gradually get closer If you don’t watch closely, they’ll nose right into you before you know it.

Sometimes one plane will fly along in line with you dipping his wings to attract attention while a lot of other planes sneak in on you from the other side. You have got to be on the alert all the time.

When you shoot at him and he peels off, don’t worry about whether you got him. It doesn’t pay to watch him. While you are doing that, another one might sneak up on you. Just use common sense. That’s all it takes.

25

THE upper turret is a good position. You can see any plane that is in position to do damage to you. Also from there you can let the ball turret know when a plane is coming in and from what position so that he can take a crack at him.

We had good teamwork on our ship. I think that is the main reason we were able to complete our 25 missions without a casualty. lt doesn’t pay any dividends to have trouble in the crew. All of ours were good boys, and we worked together and had confidence in each other.

Before going over, bomber crews should get used to high altitude flying. It gets cold up there and gunners should get accustomed to it. The first time most of the fellows see an electric suit is after they get over there.

We had a lot of excitement. I’ll never forget our March raid on Rouen. We flew over the French coast, feinted, and flew back across the channel. We knew the Jerries would get wise some time, and they did. They jumped us over the channel, 30 or 40 of them. They attacked from every position. Then just after we dropped our bombs, more fighters came from out of nowhere. Our tail got hit. We weren’t bothered much more until we got almost to the channel. Then six of them jumped us, circled around our tail from seven o’clock to five o’clock, and went to work on us. Shells were bursting everywhere. Finally, the foremost fighter began to smoke. He turned away and the rest followed him.

26

We hear they get an Iron Cross when they shoot down a B-17. They are a pretty determined bunch. When you cross into enemy territory, you have a tense, expectant feeling. You never know just what you are getting into. But get busy, and then you are okeh.

TECHNICAL SGT. ROBERT J. HANSON

Radio Operator

Sergeant Hanson was a construction worker in Spokane. Wash., before joining the Army in September, 1941. He is 23 years old, married.

HIS STORY

IF you are in a new combat crew, you would do yourself a favor to sit down and have a good bull session with men who have been through it. Talking to them, hearing what they did and how they did it, you can pick up things it would take you a long time to learn for yourself.

Also, you should get accustomed to talking over your interphone. Learn not to talk in an excited high-pitched voice. A little noise on the interphone going over always helps, because everybody is nervous. When you are in combat, use the interphone to keep the rest of the crew informed about what you can see. In a fight, the interphone is one of the most important things on your ship.

You will find that Jerry is fond of putting out false signals and false beams to confuse you. You have to be careful.

27

There Should be others on the crew besides the radio operator who can code. There is always a chance that somebody will be hit, and it may be the radio operator. The ball turret gunner or the tail gunner should be able to take messages by blinker code if the radio operator can’t see them.

Practice wearing your helmet before you go over. If it doesn’t fit, get it fixed. You probably won’t be able to get it fixed over there. At best, our helmets aren’t satisfactory. The wind whistles in, and if you pull them tight they hurt your eardrums. The British helmet is far superior to ours.

WE have been in some pretty tight spots. There was the time that six Focke-Wulfs appeared from nowhere, and all six cut loose on us. We could see cannon shells bursting around us and had to slug it out with them. One of the fighters started smoking and went down. We headed in the direction of another, and after that they left us alone.

The radio operator’s position is a good one, but it’s a rough place to ride. In the Lorient raid, when we got the tail shot off, Captain Morgan put the ship into a terrific dive and we dropped two or three thousand feet. It pretty nearly threw me out of the airplane. I hit the roof. I thought we were going down and wondered if I should bail out. Then he pulled up again and I landed on my back. I had an ammunition box and a frequency meter on top of me. I didn’t know what was going on.

28

Captain Morgan didn’t have time to tell us and I couldn’t have heard him if he had.

American morale in England is very high, and the boys are really on the ball. The fellows would enjoy more current magazines. About the only one we got was Readers Digest. By the way, the Red Cross does a swell job. If it weren’t for them, we couldn’t have gone to London because we wouldn’t have had any place to stay.

STAFF SGT. JOHN P. QUINLAN

Tail Gunner

Captain Morgan calls him the “horseshoe of the outfit.” He has had more close calls than anybody else on the crew. Short, stocky, 24, comes from Yonkers. N.Y., worked for a carpet company before joining the Army December 8, 1941. He, too, wants to be a fighter pilot.

HIS STORY

I like being a tail gunner. It’s my own private little office back there. I sit down all the time, and when I get a chance, I relax. I get a lot of good shots too.

The tail gunner is in a good spot to help the pilot by telling him over the interphone what’s coming up from behind. But he should be careful to call out only the ones that are attacking. If he calls everything he sees — one at five o’clock, one at seven

29

o’clock, one at six o’clock – get the pilot so confused he won’t know what’s going on. He should call out only the ones that are after him.

Don’t be afraid to use your ammunition but don’t waste it. That is the best advice I can give.

YOU’VE got to be alert all the time. You never can tell what will happen. The time they shot my guns out and hit my leg, I hadn’t expected any trouble at all. I thought that mission would be a cinch. It was a short raid and we were going to dip in and pop out again. Just after bombs away, I thought I saw flak. It wasn’t, it was fighters.

A fighter will climb until he thinks he can give it to you, then he’ll dive on you. That’s what this one did. I looked up just in time to see his belly. It always gives you a funny sensation to see the big black crosses on the wings. I could hardly miss him. I got him. He burst into flames. I guess I was gloating over the one I got. Then I saw the other one. It looked like he had four blow torches in his wings. All of a sudden, it sounded like somebody hit the tail with a sledgehammer. It got my guns and me.

But the one I got the biggest bang out of was the Lorient raid. Captain Morgan went up, then down. I lost equilibrium. I didn’t know whether to jimp or stay there. I didn’t know what was going on. That was the time horizontal stabilizer got on fire. I guess it was the wind that put it out.

30

STAFF SGT. CASIMER A. NASTAL

Waist Gunner

He is the baby of the crew. At 19, he has two confirmed fighter kills to his credit, thinks he has knocked down others “but never had time to watch whether they went down.” Used to have a job repairing washing machines in Detroit. Entered Army December 24, 1941

HIS STORY

MY first advice to gunners is to take good care of their guns. This is important. They shouldn’t depend on anybody else to do it for them. Every gunner should see that his oil buffer is set right. He should check his electrical equipment before taking off, because it gets cold up there and if his equipment isn’t right, he’ll suffer.

The Germans will try to fool you. They’ll come in and attack, and then as they pass, they’ll let out a streak of smoke as if they are going down. Then they’ll come back. Also, they try to imitate our escorts. They get where you can hardly see them and unless you watch closely you might think they are your own fighters. Then suddenly they’ll break in fast as hell and start shooting. If you have escort, you’re likely to be less alert than when you don’t have them. But if you’ll keep alert, you’ll be okeh.

Always watch the other gunners if you can. If you are a waist gunner, watch the other waist gunner. If he needs help, give it to him. He may have attacks coming in and be short of ammunition. If he is, give him some of yours.

31

Combat crews should never go into combat with the idea that they are not coming back. Those who have that in their minds are the least likely to get through.

IT’S always a great thrill to get a fighter in your sights and let him have it. I don’t know how many I have hit, but I have two confirmed. I’ll never forget the day one came in shooting from 5 o’clock. I let him have it and saw my tracers go into his gas tank. He went down. I didn’t see the pilot get out.

The Germans are a wild bunch sometimes. On our Bremen raid, the fighters came in bunches of 20 or 30. At the target, the flak started. It was bursting outside the waist windows. I could have reached out and grabbed it. I kept thinking, “Let’s get the hell out of here.” I saw two or three fighters hit by their own flak. It was so thick you could hardly see the ground. The Focke-Wulfs were even bursting through our formation.

You can see the effects of our missions. In England, they used to call St Nazaire “Flak City.” The raids have softened it up.

At the waist gun position, you can see what’s going on just about anywhere. It’s cold, but when you’re in flak you warm up. You don’t have time to think about being cold. You don’t have time to think about being scared either. You might be scared on the way over. You think of all the things that could happen. A lot of funny things run through your mind.

32

I want to go back as a pilot. I put in for fighter pilot, but if they give me a B-17 I’ll take it. I guess it just gets in your blood.

STAFF SGT. CECIL H. SCOTT

Ball Turret Gunner

Before going into the Army January 12, 1942, Sergeant Scott was a pressman for a rubber company at Rahway, N. J. He is 27, oldest member of the crew, wants to be a gunnery officer.

HIS STORY

THE ball turret is the best position on the airplane. You see a lot of action in that position, you know what’s going on, and you are always busy. If the plane catches on fire you know it first because you can see all four engines, and you can get out as quickly as anybody else.

It isn’t too uncomfortable. Of course, a big man shouldn’t have the ball turret. I’m small, and I get along all right. I was in it seven hours one time and didn’t get very tired.

You should get as much practice in the ball turret as possible. Practice using the sight, operating the turret, and getting in and out.

THE Germans have some tricks that you’ll soon know if you are alert. When they attack and come under the ball turret, they turn sideways or clear upside down. They go into a slow roll and they are

33

awfully hard to hit. Sometimes they’ll shoot out smoke to make you think they are hit. I have seen ME 109’s come out of the clouds and hang on the prop under our ship, probably to try to hit our bombs.

Before the attack, you are usually scared, but when the planes start coming up and attacking you are all right.

I have known fighters to follow us for 15 minutes before attacking. They seem to be looking us over while they circle around, trying to decide where to attack. When you see them start to peel off, you’d better start shooting.

If you can’t get a good shot, you might be able to figure out a way to change the position enough to make it possible. For instance, if you get a plane at the right wing where you can’t hit it, you can ask the pilot to lift the wing.

On the Rommily-Sur-Seine raid, about 300 fighters attacked us in relays. The fight lasted a couple of hours, the longest one we had been in. They attacked us as soon as we crossed the coast and circled around us like Indians. Then they started attacking from all directions at once. I thought I got two, but I didn’t get credit for them. We kept plugging away at them and somehow got by. Practically all our ammunition was gone when we got back. As many times as they shot at us, we didn’t get a single bullet hole in the plane.

Last winter American morale in England got pretty close to the breaking point because we weren’t getting any replacements. It’s good now.

34

STAFF SGT. CLARENCE E. WINCHELL

Waist Gunner

Sergeant Winchell was a chemist for a paint company in Chicago before joining the Army in March 1941. He is 26 years old. He wants to be a gunnery officer.

HIS STORY

YOU can see that Germany is getting desperate. A good example of the things they are trying is dropping bombs on our planes from above. It isn’t effective, but it’s something that bomber crews should watch for.

They seem to be pulling their defenses back into Germany itself. St. Nazaire used to be tough, but it’s not so bad now.

Although some of those places in the occupied countries are easier than they used to be, they still are no snap. It’s good advice never to sell a target short, because you may get a surprise.

You’ll still find stiff fighter opposition. The Germans seem to be trying to feel us out, trying to learn more about us and our ships. They have gone from mass attacks to single attacks and back to mass attacks.

Our crews should have more high-altitude training. Bombers and fighters should be in the air at the same time on these training flights so that they can get accustomed to each other and learn what to expect.

35

The interphone is the most valuable piece of equipment on the ship. Most of the fellows would rather go over with half their guns out than with the interphone out.

Bomber crews must not relax just because they are out of enemy territory. They jumped us once in the middle of the North Sea and damn near shot us down.

THERE is one incident that stands out in my memory. It was on the Emden raid. We had bombed our target and the fighters were after us. I never saw such crazy flying as they were doing. One Focke-Wulf came in at 9 o clock and seemed to be concentrating on me personally. I was looking down the barrel of a 20 mm. He went over our left-wing ship and under us. I don’t know yet how he managed to slip through. I was petrified.

The Memphis Belle had no better crew than a hell of a lot of other B-17’s. If there was anything remarkable about our taking all we did without a casualty, it was a combination of things. We had some luck. We had a good crew, and what’s just as important, we had absolute confidence in each other.

36