Many of our followers are not on Facebook and I would hate to deprive them of an opportunity to see these additions. So here is a post detailing some of the smaller odds and ends we finished in the past couple months.

Many of the pieces below are from our Auxiliary and Radio Parts Drives. We have made amazing progress of these drives in the last year and are fast approaching the end. Right now, the most pressing drive needs are A-2 and A-17 fire extinguishers, the chemical toilet, and vast quantities of off-white fabric-covered wire.

If you would like to contribute to the rebuilding of Lucky Thirteen or would like to volunteer, do not hesitate to contact us. If you are fabricator (metal, fabric, etc.) and would like to help, we will happily send blueprints your way!

Photo taken 3 September 2019.

Projects like this cannot survive without donations, both financial and material. Still, in today’s trying times it is always a pleasant surprise when someone chooses to send something our way. Thus far though, this one takes the cake. When Charlie sent these pictures, I had to sit down and catch my breath.

Jack Antonio (WA7DIA) of Warner-Robbins, Georgia contacted Charlie about a collection of equipment he wished to donate to Lucky Thirteen. From what I heard, I knew this was going to be big – but I didn’t expect something this awesome. Thank you very much indeed, Jack!

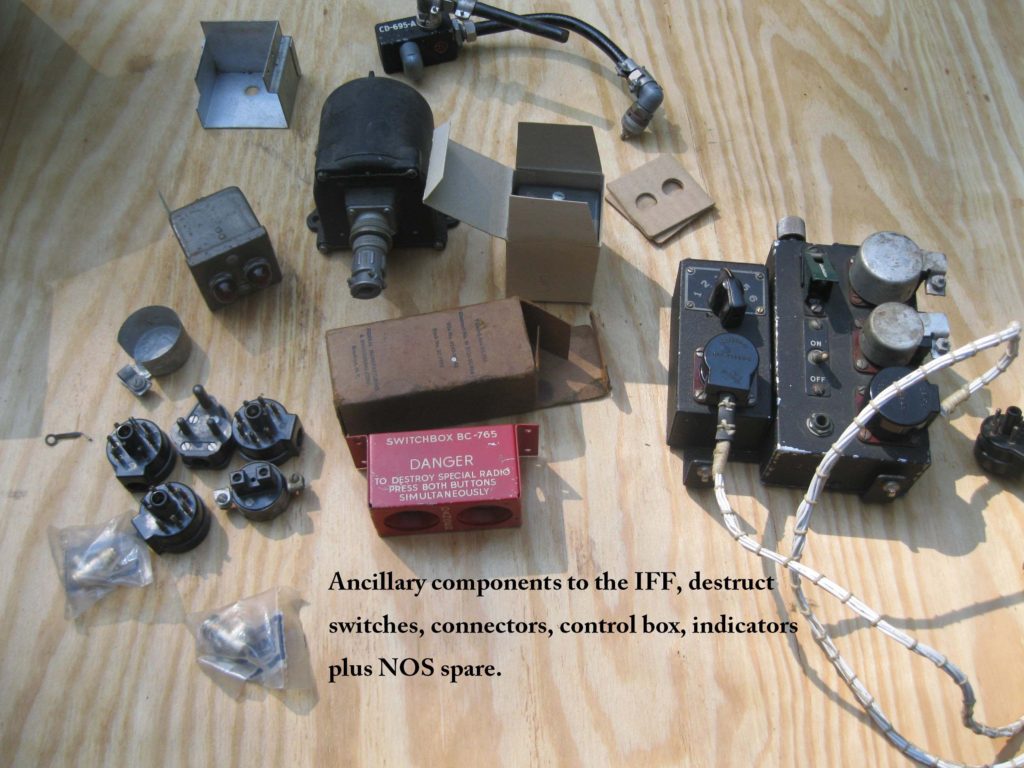

Amongst the equipment Jack sent our way, the absolute rarest was a complete IFF system.

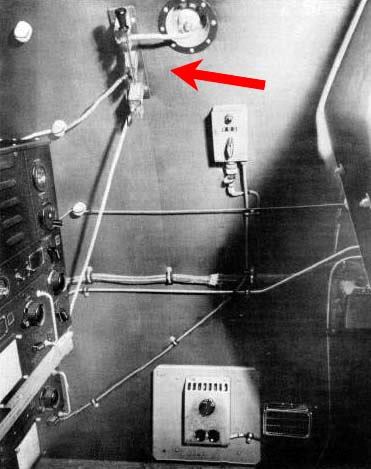

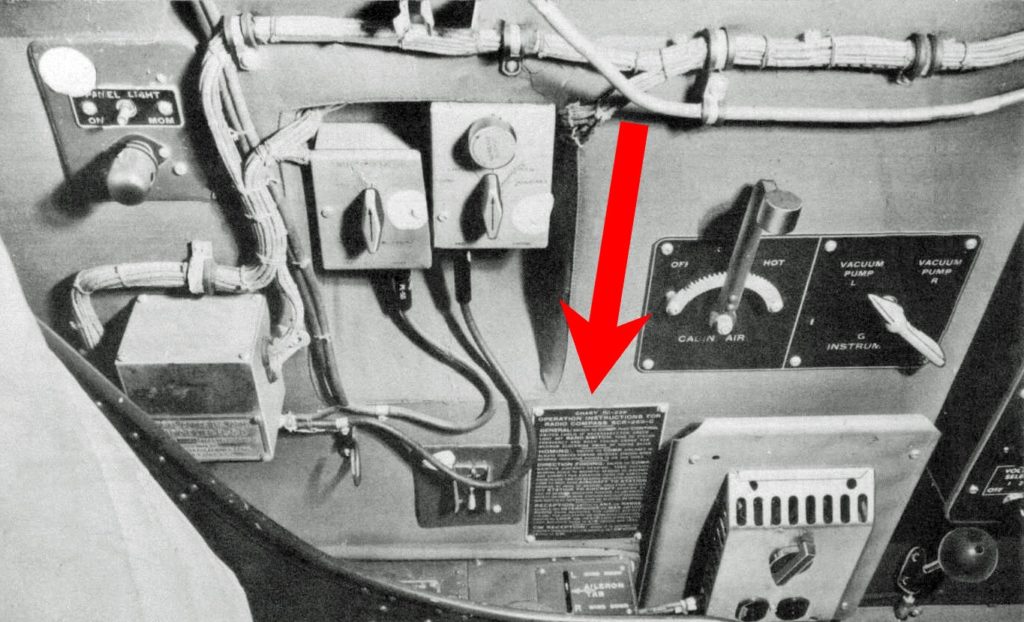

The IFF’s transponder was mounted on the back of Station 6, above the dynamotor for the Liaison Radio. Though barely visible in this photo, the BC-727 indicator light was mounted on the bottom of the shelf holding the transponder.

Note the silver tube below the arrow – this is a Bullard Cylindrical First Aid Kit. Bullard is a personal protection company in Lexington, Kentucky and is still in business. Most B-17s carried as standard three canvas First Aid Kits – one for each crew compartment – and a Bullard can for the waist section.

When the National Museum of US Air Force brought the Bullard cans to our attention, they asked if we could recreate the label for the one on Memphis Belle. We were happy to do so. You can see it in our very first update.

Photo taken 3 September 2019.

The controls and connectors for Jack’s donated IFF system are laid out. To the right is the RC-255 case which holds the BC-958 Control Box and BC-965 Selector Box, both of which were mounted above the radio operator’s table. The black cylinder at the center-top is the BC-706 Inertia Switch. While we already had one, this one is better shape and is the older variant with the cannon plug. The red box at the bottom is the BC-765 Self-Destruct Switch, one of several self-destruct mechanisms for the IFF.

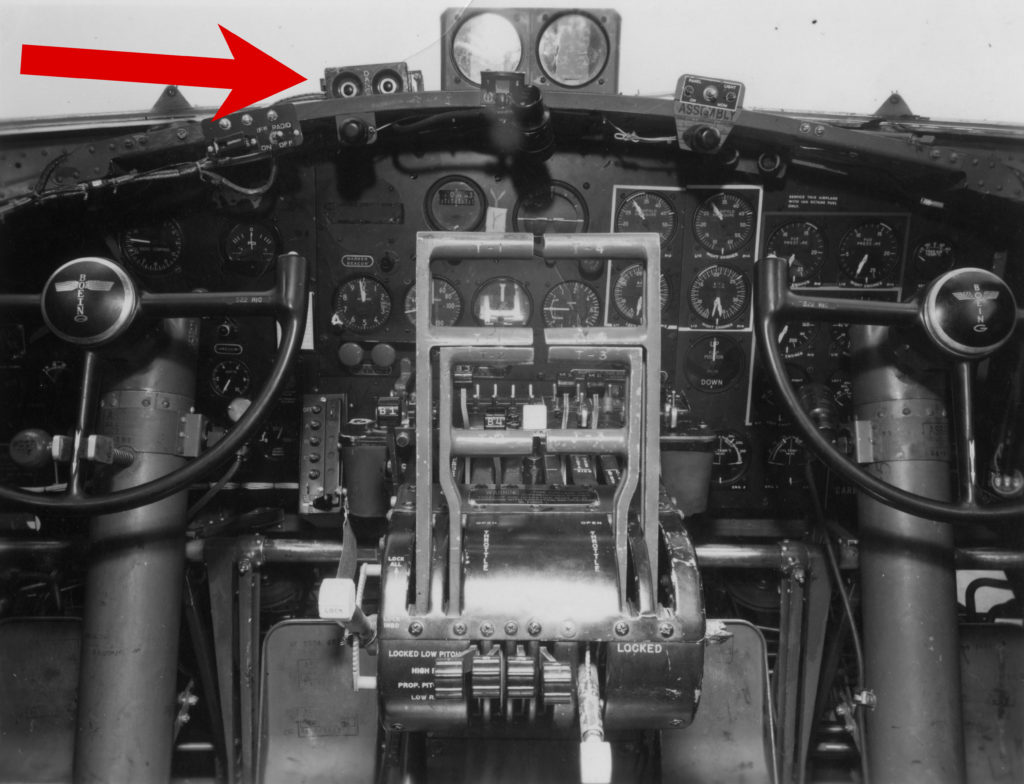

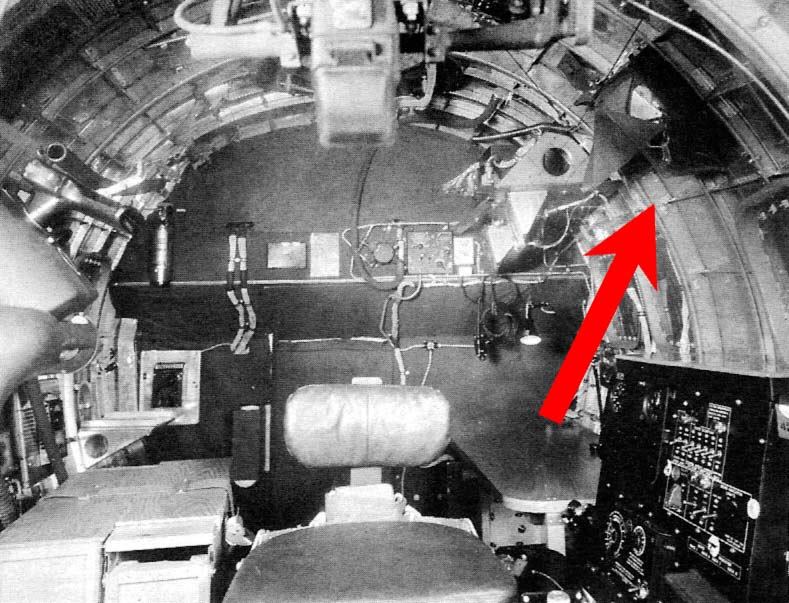

Like the Norden bombsight, wartime photos of IFF systems are rare due to their official secrecy. In this photo – taken from a late-B-17G – the BC-958 Control Box, BC-965 Selector Box, and BC-706 Inertia Switch are all visible on the wall above the radio operator’s desk. The Inertia Switch was designed to set off an explosive charge in the transponder whenever violently shaken. Similarly, the Control Box featured a manual self-destruct as well.

The brass fire extinguisher on the right is a Type A-2 Carbon Tetrachloride extinguisher made by Fyr-Fyter of Dayton, Ohio. There were between two and three of these on any given B-17. If you have an A-2 and its mount and would like to contribute it to the project, please let us know!

Photo taken 3 September 2019.

A close-up of the recently-donated BC-706 Inertia Switch. The plastic cap is removable, allowing one to reset the spring in the event of an accidental discharge. I cannot help but wonder how many airmen fried the IFF by coming down just a little too hard on landing.

Photo taken 3 September 2019.

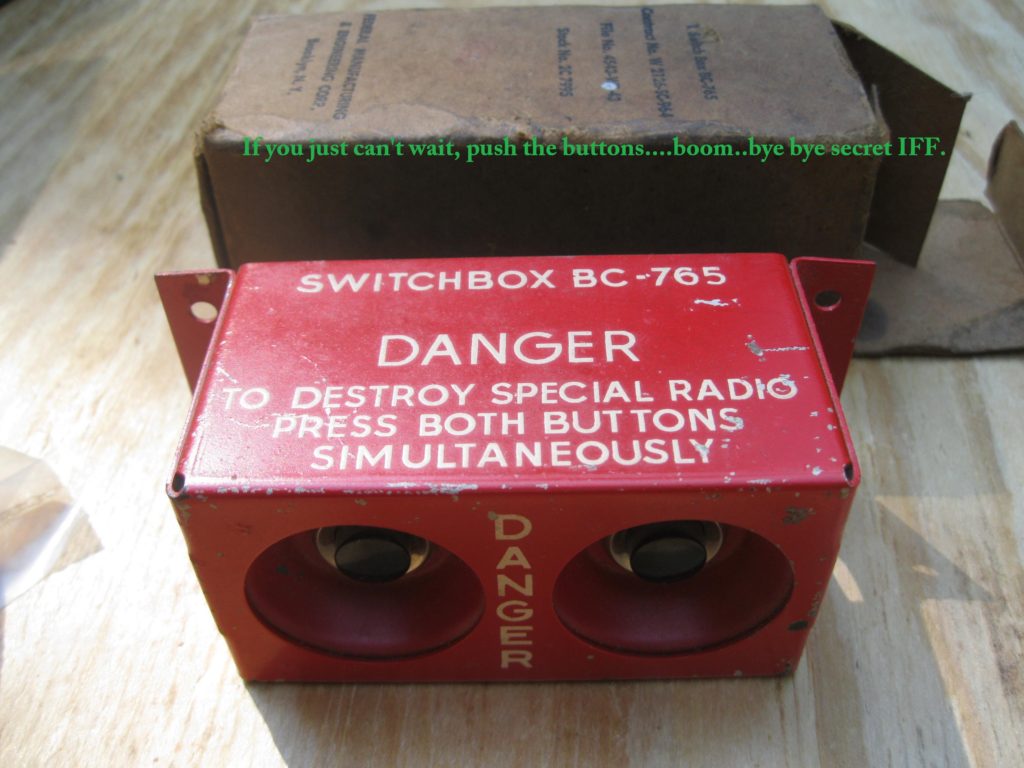

A close-up of the recently-donated BC-765 Self-Destruct Switch. This switch comes to us still in its original box, marked as being made by Federal Manufacturing and Engineering of Brooklyn, New York. No longer is business, Federal Manufacturing specialized in making photographic enlarging equipment in peacetime.

The pilot’s BC-765 Self-Destruct Switch is highlighted in its place on top of the pilots’ instrument panel.

Photo taken 3 September 2019.

Great care must be exercised when the IFF system is displayed as many Second World War frequencies are still in use. Regardless, Jack was kind enough to provide us with the equipment necessary to test the system and ensure it is properly functioning. The only IFF piece we lack is the self-destruct mechanism for the transponder – which we’re going to leave alone!

Photo taken 3 September 2019.

The IFF’s Type AN-95 antenna is displayed alongside a BC-434 Control Box for the SCR-269 Radio Compass. While we had two of these control boxes, one of the two lacked a mounting plate. Jack’s donation solves this problem. We are now ready to restore and display the Radio Compass System.

The AN-95 IFF Antenna is highlighted in this screencap of Memphis Belle.

If you have not seen it, you might want to check out the new documentary The Cold Blue (2018). While there is little new for B-17 enthusiasts in terms of content, the team behind the film did an incredible job restoring the footage taken by William Wyler’s teams some 76 years ago. Likewise, the interviews with veterans are well-done are a joy to listen to.

Photo taken 3 September 2019.

The recently-donated Reel Antenna System is laid out. The egg-shaped piece in the center is the WT-7 antenna weight; weighing roughly 2 lbs, the weight dangles from the end of the spooled wire. The RL-42 motor, to the upper right, spools the wire in and out of the F-10 tube (not shown), which sticks out the side of the airplane. The control for this assembly, the BC-461, is on the bottom right and is positioned to the left of the radio operator. The cabling which connected the motor to the control is on the left. Splined cabling like this is difficult to find and we are fortunate to have the support of people like Jack Antonio and Steve Williams in locating and, when necessary, recreating said cabling for Lucky Thirteen.

The ball at the top of the picture served as the plug connecting the inside of the airplane to the outside. This ball plug was only used on B-17Gs, and as such, is not correct for Lucky Thirteen. The older style plug can be found in blueprint 3-15106.

*The older style plug has been fabricated since this update.

SSGT Ralph E. Azevedo poses in his position as Left Waist Gunner aboard Qualified Quail (42-97851, 91BG). The RL-42 Reel Antenna Motor and Spool is highlighted here.

Damaged over Cologne, Qualified Quail crash-landed in Allied-occupied France on 14 January 1945 and was salvaged. Azevedo was not with them, having been previously wounded and, upon recovery, transferred to another crew.

Photo taken 25 August 2019.

A close-up of the knots, the whipping, and the snaps on the newly-finished bomb bay guard rails – a small part that was deceptively complex to make.

Blueprint 3-7194 called for the rails to be made of .75 inch, 3-twist cotton dyed dark green. Each end was to have a .75 inch swivel snap held in place with an eye-spliced knot. Two lengths of the rope were to be 52.5 inches and the other two 30.5 inches.

While I had no problem dying the rope, I am no good at tying knots. In fact, an early Facebook post saw us reach out for help on this. Help first came in the form of Sailor Craft Knots of Charleston, South Carolina, who donated his time to the project. I sent him the materials and he went to work.

Unfortunately, we ran into a problem. The ropes came back with a different splice. It turned out that the swivels were too small to run the rope through, so he had to use a different knot. The ropes from Charleston were perfectly done, and to be honest, our reference pictures were not clear enough to prove otherwise. Still, I wanted something a little closer to the prints.

The ropes you see here are the final product. These were made by R & W Rope of New Bedford, Massachusetts. Professional knot tying is rather expensive, but Ray Rios offered us the best discount they could manage. They even called and sent photos to ensure we were happy with their work before finishing the order. The knots were feathered and wrapped with wax-lacing cord (as per the blueprints) and Megan and I dyed them once they arrived back home. The only alteration was to use a slightly larger snap to ensure the rope could be adjusted freely.

1LT Louis A. Dentoni poses for photographers aboard Lulu Belle (42-30187, 385BG) in September 1943. The photoshoot was intended to document the unit’s youth: of the 385BG’s officers, the youngest was 20, the oldest was 39, and the group’s CO, COL Elliott Vandevanter, Jr., was 26.

Dentoni was 24 when he was killed on 6 March 1944 – the US 8AF’s first strike on Berlin.

Not only is this one of the few wartime photos where you can make out the bombbay guard rails, but also visible is the Portable Oxygen Bracket and Oxygen Hose mounted on the bayside of Station 5. These pieces allowed crewmen to work in the bombbay for extended periods, such as when a bomb failed to release.

Photo taken 24 August 2019.

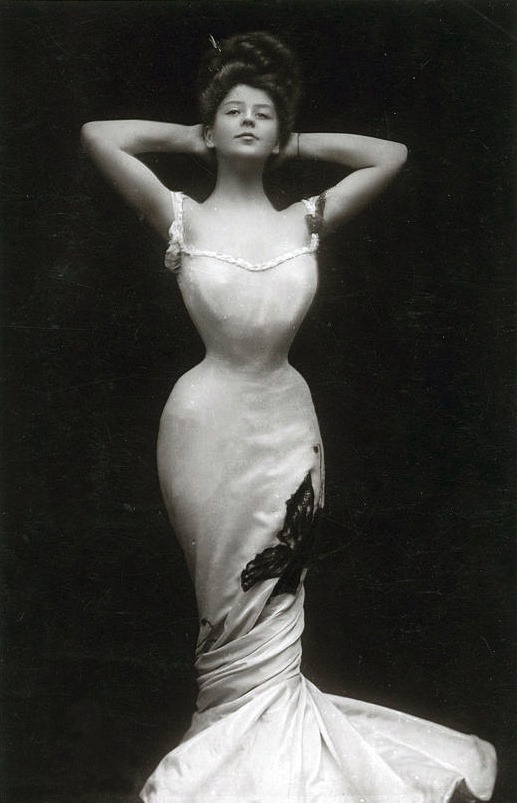

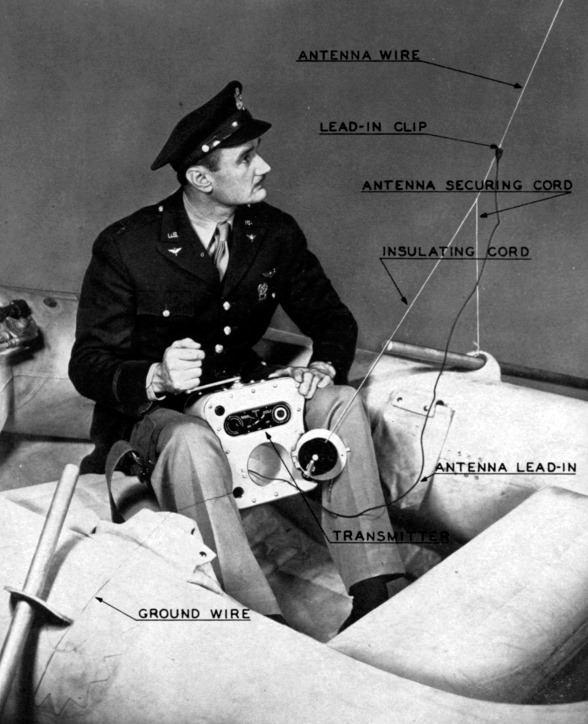

The SCR-578 was the standard emergency radio for large US aircraft in the Second World War. The system was built around the BC-778 transmitter, a small yellow radio with a distinctive hourglass shape. This is the origin of the nickname “Gibson Girl,” a reference to the old 1900s pin-ups with the sharply pinched waists.

The idea behind the radio was rather ingenious. The airman was to squeeze the unit between his legs and turn the crank on top to charge it. The next step depended on the weather. On a still day, he was to use a pair of hydrogen generator canisters to inflate a small balloon, but on a windy day he was to use a collapsible box kite; both were designed to serve as antennas. In theory, the Gibson Girl unit would allow a downed airman to convey that he was alive and awaiting possible rescue.

Gibson Girl sets are highly prized today and the most common are B models and postwar AN/CRT-3s. Since Lucky Thirteen saw service in 1943, she was almost certainly fitted with an A model. The difference is primarily in the bags – the AN/CRT-3 and B model had one bag, the older A model had two. Both bags were mounted beside the ball turret.

Type A Gibson Girl radios and bags are difficult to find, as are intact kites, so we are extremely happy to have found both an BG-110 bag and MC-357 kite. This is only half of the Gibson Girl set but it is a wonderful start.

Photo taken 24 August 2019.

The BG-110 bag for the SCR-578-A Gibson Girl emergency radio. The folds in the top are for the small M-276 parachute, which is missing on this example.

Photo taken 24 August 2019

A close-up of the BC-778 Transmitter. The door holds the spool of wire to connect to the balloon or kite antenna.

Radios were rarely given a coat of primer, and since the Gibson Girl was stored on the floor by the ball turret, it is not unusual for this wartime example to be heavily scuffed.

Photo taken 24 August 2019

A close-up of the back of the BC-778 Transmitter. The handle stowed here (the safety pin is missing) is used to turn the hand crank on top of the radio, charging the transmitter.

A reaction to the suffragette movement at the turn of the century, Charles Dana Gibson’s pin-ups combined a series of features ideal at the time: a slender figure with broad hips and bust, a sultry face, and a mass of wavy hair the model struggled to contain above.

Gibson’s pin-ups usually featured women performing athletics or lording over men with their feminine wiles. In concept, Gibson’s ideals were no-different than those of today’s sex-based advertising.

These drawings used several women as models but the most popular was Belgian-born Camille Clifford, shown here in 1906. Famed for her 18 inch waist, she retired from public life after her husband was killed in the Great War.

Photo taken 24 August 2019

The M-357 box kite, fully unfolded on the floor of my living room. The carrying tube for the kite sits beside it for scale.

A manual excerpt shows the BC-778’s spooled wire being connected to the M-357 box kite.

A manual except shows how the BC-778 Transmitter is held between the legs and cranked for a charge.

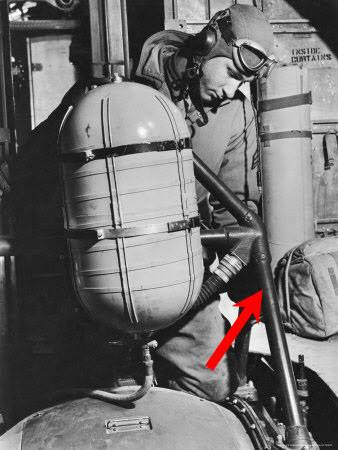

SSGT James M. Abbott, 97BG, adjusts the oxygen tank that feeds his Type A-2 ball turret.

The two early style Gibson Girl bags are highlighted with a red arrow.

Photo taken 14 August 2019.

Midlake Products & Manufacturing of Louisville, Ohio kindly donated a set of sixteen door hinges for Lucky Thirteen. Our contact, Joel Rich, oversaw the creation of these hinges, which were laser-cut to exactly match blueprint 1-18266. Thanks Joel!

In wartime, these hinges were provided by Stanley Hardware (who are still around) and were identified as AL808. Not only were these hinges used on the B-17’s three main interior doors, but they were also used on the wooden entry ladder as well. Much of the reproduction ladder has already been built, as we were waiting on these hinges to finish it up. Ray is excited too, as he is eager to go ahead and mount the doors to Stations 4 (the cockpit back wall) and 5 (the radio room front wall).

The tail gunner’s crawlway door will need a different type of hinge: a 4” hinge found on blueprint 1-18814.

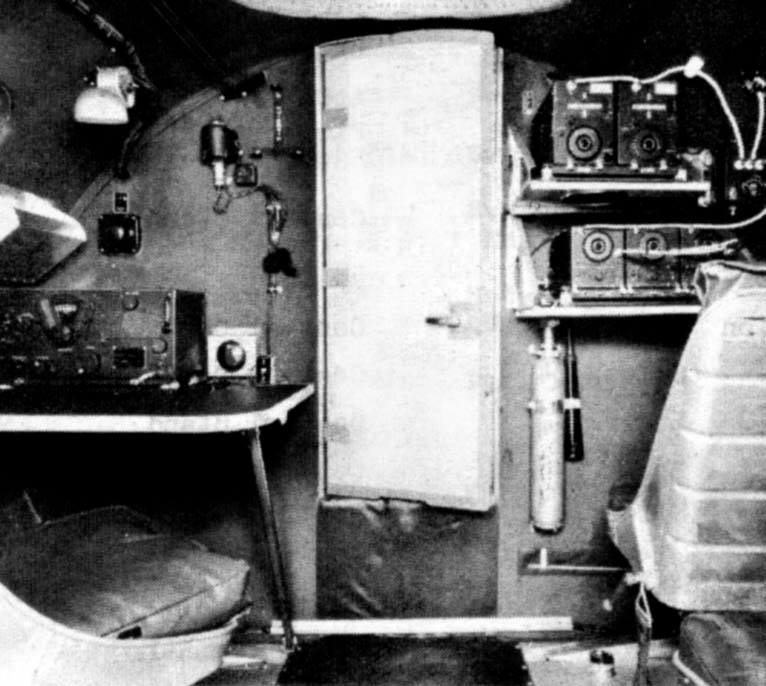

This manual photo shows the interior door of Station 5 (the radio room front wall) in an early-B-17F. Note the three hinges on the door.

The fact that this is an early-F can be ascertained by the linoleum-covered metal desk, the aluminum bucket seats, and the older black-finish Command Radios. Note how, for security purposes, the IFF controls have been removed from the wall, leaving behind the T-shaped mounting bracket.

Photo taken 9 August 2019.

This piece comes to us courtesy of Brian Freer from across the pond: it is a pair of armor plates for the B-17’s pilot and co-pilot seats.

A little history:

The Army Air Corps lacked powered gun turrets at the start of the Second World War. Learning from the British experience, the US undertook a crash-program to arm its bombers with electric turrets in 1940. However, tests at Wright Field using a Martin B-10 and a Curtiss P-36 concluded that head-on attacks were more “a threat rather than an effective method of employing firepower.” As such, US bombers went to war without effective forward-facing armament.

On 23 November 1942 – just three months and six days after the first 8AF strike against occupied-Europe – Luftwaffe interceptors began using head-on attacks as standard procedure against B-17s and B-24s. American airmen quickly began altering their bombers to include additional armor and forward-facing machine guns, no matter how clumsy. It would not be until the following autumn that forward-facing powered turrets began arriving.

It is rather fascinating to see how the blueprints account for these attacks. B-17E 41-2505 – the first B-17 equipped with a ball turret – was also the first to be factory-equipped with armor plating on the pilots’ seats. Made of stainless steel, these plates varied between 3/8” to 5/8” in thickness and were very heavy. It is for this reason that few surviving B-17s still have them.

Happily, we can restore these plates to factory condition with ease. The first step will be to clean them. We can always use some more hands…

1LT Bob M. Welty of the 398BG peers over the armor plate on his seat. Note the flare shelf on the back, which we recently recreated.

Also of interest are the remnants of a chart glued to the armor plate itself. The seats featured operations charts with copious numerical figures on the aircraft’s operation. Thanks to Karl, we found the blueprints for these charts and recreated them for both Lucky Thirteen and Memphis Belle (though the two were quite different).

Photo taken 5 June 2019.

This is the little shelf which holds the 37mm Cartridge Pouch.

As per the blueprints, the shelf is made of 3/16 (3-Ply) Douglas Fir, with the spacers made of spruce and the arms of 3/8 Douglas Fir.

Photo taken 15 June 1943.

LTs James M. Smith and Fred N. Dibble pose aboard Our Gang (42-5069, 91BG).

Our Gang was lost over Schweinfurt on 17 August 1943.

One interesting side-note about Our Gang – interior photos of her nose compartment have proven essential in restoring the navigator’s table in Memphis Belle. Both airplanes had the navigator’s table installed on the opposite side from normal.

Photo taken 26 Julu 1943.

The rather horrific effects of German 20mm autocannon fire on a 92BG B-17 cockpit.

Photo taken 5 August 2019.

David Green of Ventura, California donated a never-used F-10 phenolic tube to the project. This tube was used with the B-17’s trailing wire antenna, channeling the wire safely through the aircraft’s skin. Supposedly, the previous owner had several F-10s and was going to use them to make a fence. Kudos to David for his donation!

As you may recall, this antenna was used in conjunction with the SCR-287 Liaison Radio system. Since it entailed spooling a length of wire behind the airplane, it was rarely used during the war. That said, it was part of the radio operator’s training curriculum and every B-17 went overseas equipped with a trailing antenna. Naturally, it is our intention to fully restore this system. We already have the RL-42 motor spool and the SW-224 knife switch; all that is left now is the wooden clamps which hold the tube in place.

*The wooden fairlead clamps have been fabricated since this update.

Photo taken 5 August 2019.

A close-up of the F-10 phenolic tube for the B-17’s reel antenna. The metal housing holds the WT-7 weight in place when the spool is reeled in

The F-10 phenolic tube for the reel antenna is highlighted on Cabin In The Sky (42-30338, 390BG).

A late-F almost identical to Lucky Thirteen, Cabin in the Sky survived the war and was ultimately sold for scrap.

Photo taken 31 July 2019.

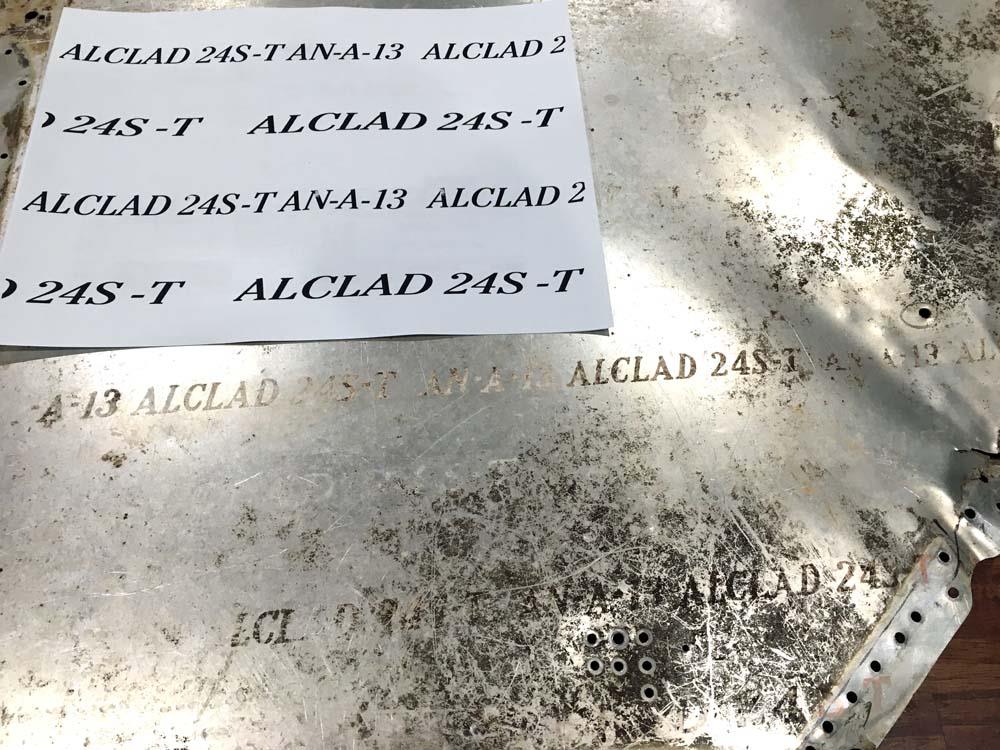

Ray has been hard at work on those bomb bays. The channels for Liberty Belle‘s bomb racks are now installed and are looking sharp. The same channels are also ready for Lucky Thirteen but there is a catch – we still need to put the identification stamps on the aluminum. These are the little red markings that were visible on unpainted aircraft during the war. My wife Megan (who is a graphic artist) has managed to replicate the typeface based on some pieces of original wreckage. We feel that the best way to apply this would be to purchase “hand printers.” These printers function like paint rollers, printing the text directly onto the metal. Unfortunately, we do not have the budget to purchase the two needed at this time.

Here the bomb rack channels are test-fitted into the bomb bay jig for Liberty Belle. This view is looking back toward Station 5 – the front wall of the radio compartment.

*The equipment needed to replicate period ALCLAD stamps has been purchased since this update.

Photo taken 31 July 2019.

The bomb rack channels are test-fitted into the bomb bay jig for Liberty Belle.

Photo taken 31 July 2019.

A printout of Megan’s recreated typeface is laid against a piece of original wreckage

Photo taken 31 July 2019.

Originals are used as patterns for new-build pieces.

Note the rear fuselage of Liberty Belle in the jig visible in the background.

Photo taken 31 July 2019.

Bomb bay pieces – original and new – are laid out for Liberty Belle and Lucky Thirteen.

Photo taken 19 July 2019.

This is a SW-224 knife switch made by the Square D Company of Detroit, Michigan. They are still in business but are now a subsidiary of Schneider Electric of Andover, Massachusetts.

This piece was kept on the wall to the left of the radio operator and functioned as an antenna change-over. There is a piece of original wire still clipped to the bottom pole.

The Liaison and Command Radio Systems both used the skin of the airplane as an antenna conductor. In theory, when one of the radios was running, you could hold a fluorescent light bulb against the airplane and light it up.

Well, the Liaison Radio is also connected to the trailing wire antenna, which is on a reel located near the ball turret. The wire reel was controlled by a small motor; whenever needed, the wire was spooled out to drag behind the airplane. While veterans have attested that this antenna was almost never used, we are nevertheless restoring this piece.

The knife switch determines which antenna is used by the Liaison Radio: the skin of the airplane or the trailing wire.

SW-224 knife switches are not particularly rare but those made for the Army Signal Corps are much harder to find. We fortunately located one some time ago but it was in need of some repairs. Thankfully, we found another switch from Tacoma, Washington to use for parts.

The seller in Tacoma is actually a member of a group restoring and maintaining the Coast Guard tug Comanche (WATA-202). Originally christened Wampanoag, she is a fully-operational WWII veteran who saw service in the invasion of Okinawa. Keeping Second World War vessels afloat – much less operational – is a monumental task, as more and more are finding themselves scuttled into artificial reefs. Kudos to those guys.

USCGC Comanche (WATA-202) in her birth at Bremerton, Washington.

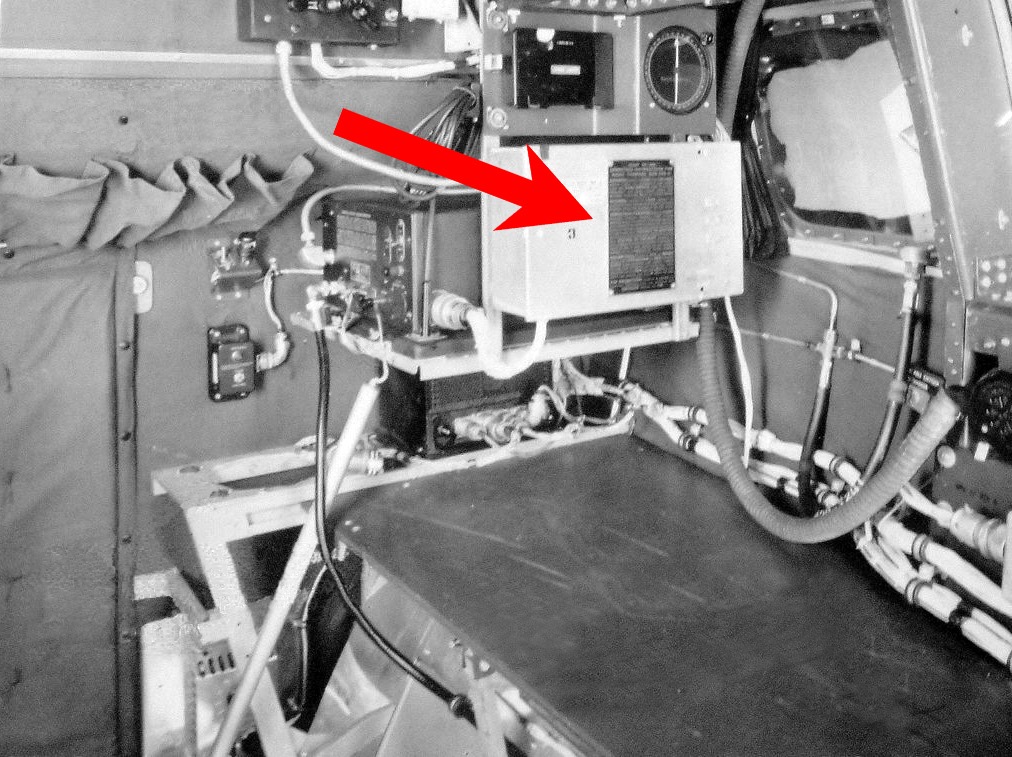

A photo from the Boeing manual shows where the SW-224 switch is installed. Late-G models used a dual-point switch rather than a single like this one.

This photo clearly shows where each piece connects to the switch. The top pole connects to the airplane’s skin, the center pole to the Liaison Transmitter, and the bottom pole to the reel antenna. Each wire is covered in ceramic beads. The BC-461 Reel Control Box is located underneath the red arrow and is connected to the reel motor assembly (beside the ball turret) via a length of splined tuning cable.

Photo taken 17 July 2019.

Charlie was able to track down a BC-306 Antenna Tuning Unit for the SCR-287 Liaison Radio System.

While designed to sit vertically, this unit was normally mounted horizontally behind the radio operator, sitting above the BC-375 on Station 6. Charlie already has a fully operational BC-375 but is keeping an eye out for a second unit so he can keep one in his shop.

This particular BC-306 is rather special in that it is an earlier variant, distinguishable by the poles on its right side – this one has two, later models had four.

This unit is in fantastic shape, needing only a little cleaning before she is ready hook up.

*We have been donated a NOS example of a BC-306 since this update.

Photo taken 17 July 2019.

The Data Plate on the newly arrived BC-306 Antenna Tuning Unit. Note the Army Signal Corps inspection stamps which note that this piece was accepted in 1943.

The BC-306 is highlighted in this photo from a Boeing B-17F radio compartment.

The BC-375 Liaison Transmitter sits beneath the BC-306. The BC-375 uses a series of a large Tuning Units, each corresponding to a different frequency range. One of these tuning units can be seen stored beneath the BC-375’s shelf.

Photo taken 13 July 2019.

Remember those Bombardier’s Data Boxes we made for Steve and Dave? Well, Steve Salinas (of the Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California) just sent some photos of their box – it’s been installed.

Turns out, the mounts for the box were still inside Piccadilly Lilly II (44-83684). The box fit in just right and Steve was able to mount it with no issues. He even used vintage flathead screws (nice).

It’s a great feeling seeing your work go on display. Thanks Steve!

A page from the Boeing manual shows the location of the Bombardier’s Data Box inside the B-17G’s nose.

Photo taken 14 May 2019.

A set of three Portable Oxygen Brackets and a Bombardier’s Data Box are finished and on their way to England. They are destined for David Littleton’s amazing B-17 Cockpit Project and were securely packaged in a box labeled “bongos.” I hope David likes them and look forward to seeing pictures of them installed!

We encourage everyone to follow Dave’s work as he shares our passion for accuracy. We intend to reach the same levels with our F that he is currently reaching with his G.

Photo taken 21 April 2019.

Toonces the Cat takes an interest while Megan and I work on Steve and Dave’s Data Boxes.

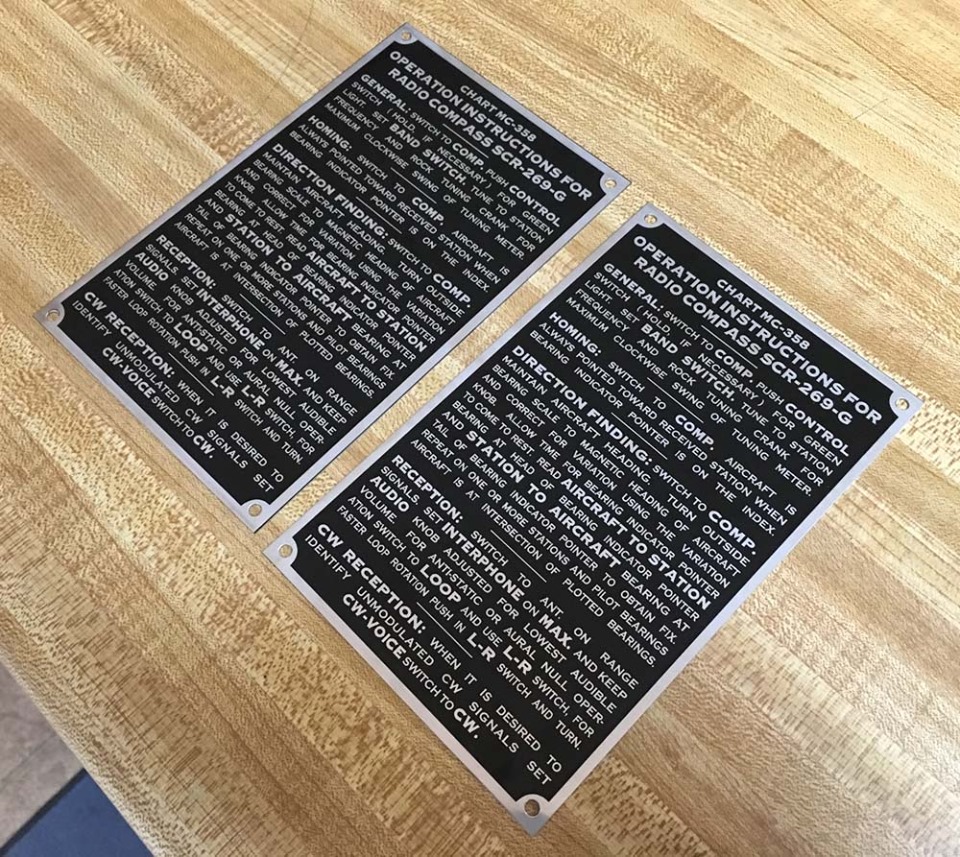

Special thanks to everyone (especially Karl and Dave) for the MC-358 references!

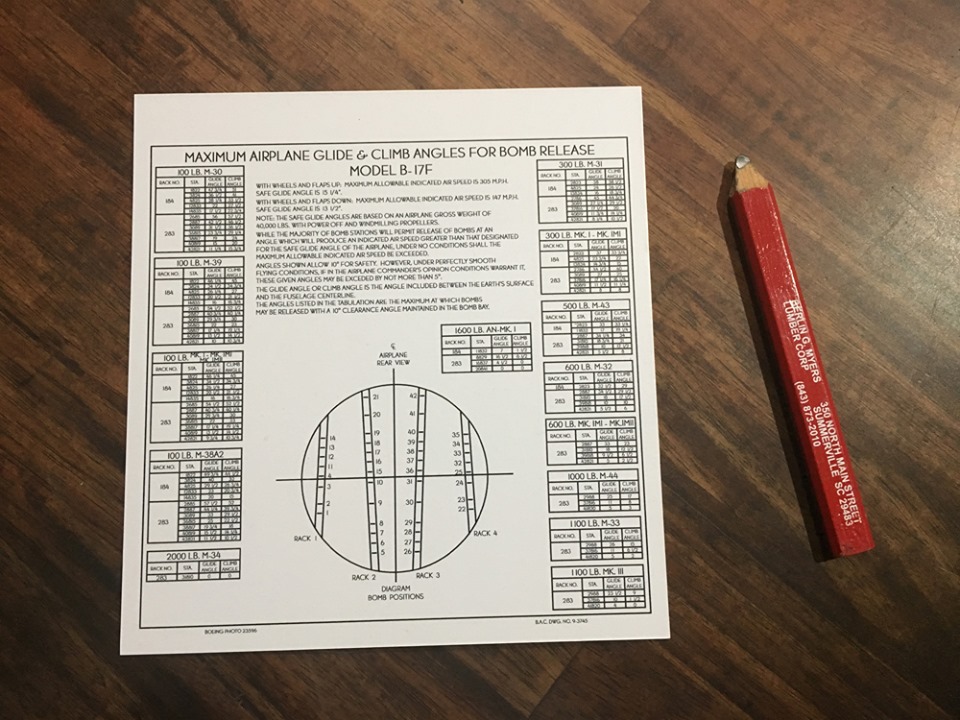

With the help of my wife Megan, we recreated the MC-358 operating instructions for the SCR-269 radio compass. The plates were printed by our good friends, Trophies Unlimited, of Aiken, South Carolina. When installed, one will be mounted to the left of the navigator and one to the right of the co-pilot.

We had four printed, two of which will go to Lucky Thirteen and two to the National Museum of the US Air Force for Memphis Belle.

An MC-358 Operating Instructions plate for the SCR-269 Radio Compass, mounted to the left of the navigator’s position.

Lucky Thirteen‘s navigator’s position will be almost identical to what you see here.

An MC-358 Operating Instructions plate for the SCR-269 Radio Compass, mounted to the left of the pilot’s position.

For some unknown reason, the blueprints call for Lucky Thirteen‘s cockpit plate to be mounted beside the co-pilot rather than the pilot.

Photo taken 3 July 2019.

Included in the package to the NMUSAF is another piece we recreated for the Belle – her Bombardier’s Glide Angle Chart. Up until Boeing Block-F-65, this piece was a small, white piece of cardstock mounted to the left of the bombardier. Thankfully, we already had some period-accurate cardstock which we used to recreate the charts for Lucky Thirteen and Belle. Now, the only chart not yet recreated for both airplanes is the pilots’ checklist.

If you have a pilot’s checklist for either an early or late-model B-17F, please feel free to send us reference pictures and measurements!

The pencil (shown for scale) comes from Berlin Myers, near Charleston, South Carolina. While a three-hour drive from here, it is the closest place we can buy Douglas Fir – the wood most called for in the Boeing blueprints.

The Bombardier’s Glide Angle Chart in a B-17E (very similar to an early-B-17F). The bombardier’s position on Memphis Belle would have been almost identical to this when she first rolled out the factory.

We were happily able to locate a clipboard just like the one seen here for the NMUSAF. Likewise, they were kind enough to send us detailed drawings and photos of the Belle’s gooseneck lamp.

*We have located an NOS example the aforementioned lamp since this update.

Photo taken 7 June 2019.

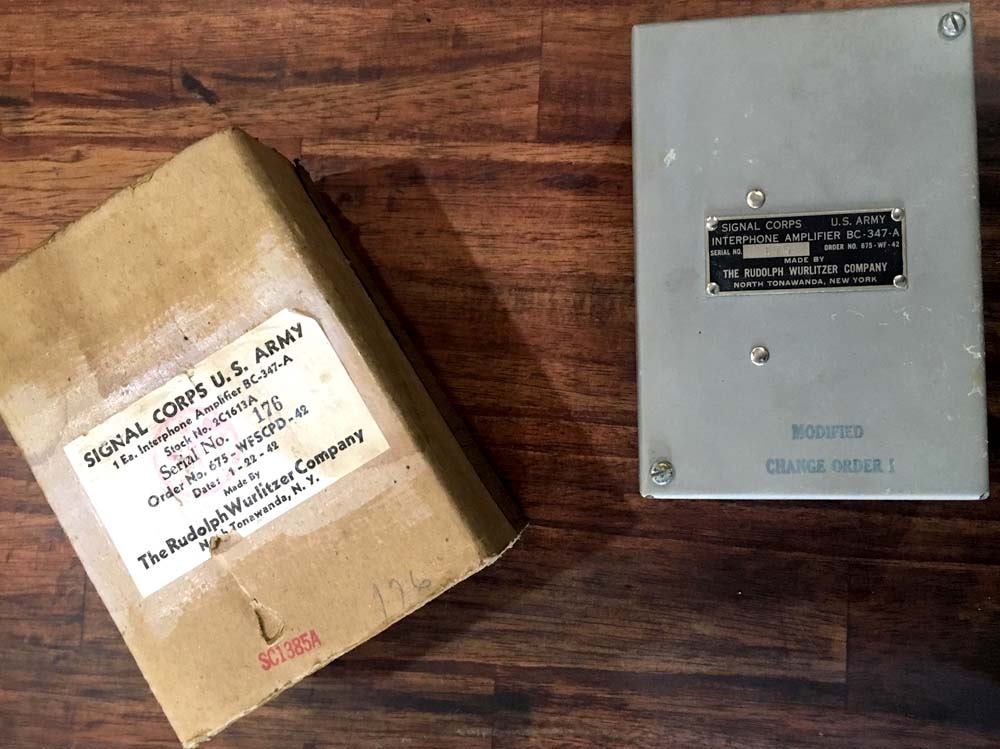

A BC-347 donated to us from Joe Hall all the way in Germany (oddly appropriate). The BC-347 served as the amplifier for the aircraft’s intercom system and was mounted on the wall underneath the Radio Operator’s desk. This particular unit was made by the Wurlitzer Company of North Tonawanda, New York.

Wurlitzer is renown in the music business for its rich history producing organs and electric pianos, though the brand is best remembered for its beautiful line of jukeboxes. Though no longer the powerhouse it once was, the company still exists as a subsidiary of Gibson guitars.

Photo taken 25 May 2019.

A donation from a little closer to home. Richard Boyens of Hickory, North Carolina donated several pieces of radio equipment to go toward Lucky Thirteen’s intercom system. Many of these pieces are NOS (New, Old Stock): clockwise, starting at the top center:

*NOS CD-307 Cord with JK-26 and PJ-055 ends

*NOS BC-366 Jack Box

*CD-307 Cord with JK-26 and PJ-055 ends

*CD-874 Cord with JK-26 and PL-55 ends and JB-47 box

*BC-347 Intercom Amplifier

*(Center Section) NOS MC-385 Headset Adapters (High to Low Impedance)

Ironically, Joe Hall’s BC-347 Amplifier was still on its way from Germany. Even knowing this, Richard still wanted to help and has also offered to volunteer his time in the hangar later this year. Originally being from England, Richard has offered to fix us some proper English tea.

I cannot tell you how awesome it is to see more and more people wanting to help. Thanks guys – it means the world to us. We need more people like Richard and Joe!

Photo taken 25 May 2019.

I couldn’t help myself….

I hook up my old headset to newly donated cord and jack box.

Photo taken 25 May 2019.

A recent purchase was a BG-81 bag for the SCR-211 Frequency Meter. We had actually purchased one earlier but it had an ugly stain on the front. Trying to remove the stain made things a lot worse, and in the end, I elected to just find another example. This one is older and rougher than the previous bag, and is more tan in color than the previous lime green. Not only is this one more likely to be a Second World War veteran, but it still has its original strap.

The frequency meter and its bag are usually missing from restorations as they were usually tied down in the radio compartment – hence the importance of the strap.

The BC-221 Frequency Meter and its BG-81 Bag aboard an early-B-17F. The B-17 made allowances for three passengers alongside its 10-man crew, with two extra positions in the radio compartment and one in the nose. The extra seats in the radio compartment (seen here) were usually removed.

Photo taken 1 June 2019.

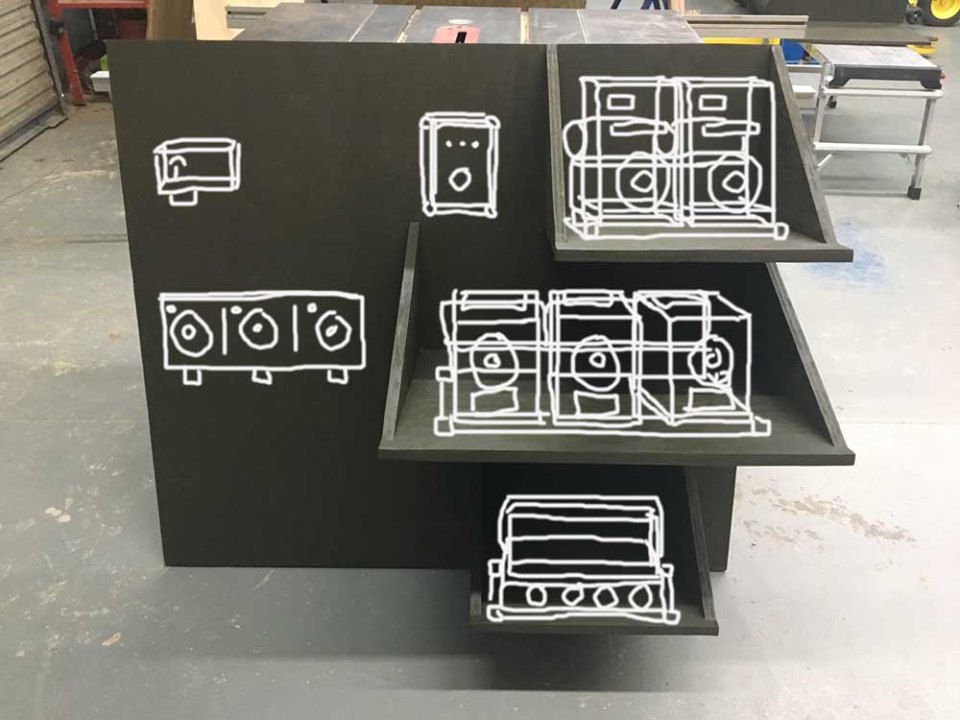

Throughout the summer of 2019 I built a series of display shelves for the hangar. They’re made out of pine so they are not particularly attractive. Still, I finished them with dark OD paint, so they have a period look to them – they certainly look like something out of my granddad’s workshop! Here are two of them.

These shelves were built to display the SCR-274 Command Radio. This is the radio system that kept a series of small units on the right wall of Station 5. The controls for this unit were actually mounted in the cockpit ceiling, using long lengths of splined cabling to connect the units to the controls.

Photo taken 1 June 2019.

Crudely drawing out a possible method of displaying the Command Radio System. The BC-457 and BC-458 Transmitters are on the top shelf, the BC-453, BC-454, and BC-455 Receivers on the middle shelf, and the BC-456 Modulator on the bottom. The BC-442 Relay is drawn mounted beside the transmitters, and the cockpit controls for these units – the BC-450 and BC-451 – are drawn mounted to the far left.

Photo taken 24 May 2019.

These shelves were built to display the giant SCR-287 Liaison Radio. This is the radio system that kept a stack of tuning units on the opposite wall. Seven in total, these units were changed out with the BC-375 depending on the frequency range needed to transmit. We have a few, but not only do we need the complete set, but the cases that held them as well.

Photo taken 24 May 2019.

Crudely drawing out a possible method of displaying the Liaison Radio System. The BC-375 Transmitter and BC-348 Receiver are on the bottom shelf and the BC-306 Tuner and PE-73 Dynamotor on top. We still need the latter piece.

Photo taken 17 May 2019.

A surprise package from Fred Bieser:

Fred sent us our very first collection of ball turret parts. The contents of Fred’s package included (from left to right): a gun sight bracket, a spent shell chute, a portion of control linkage, and an intercom foot switch.

We can hardly thank Fred enough for his help as we begin our journey toward powered turrets!

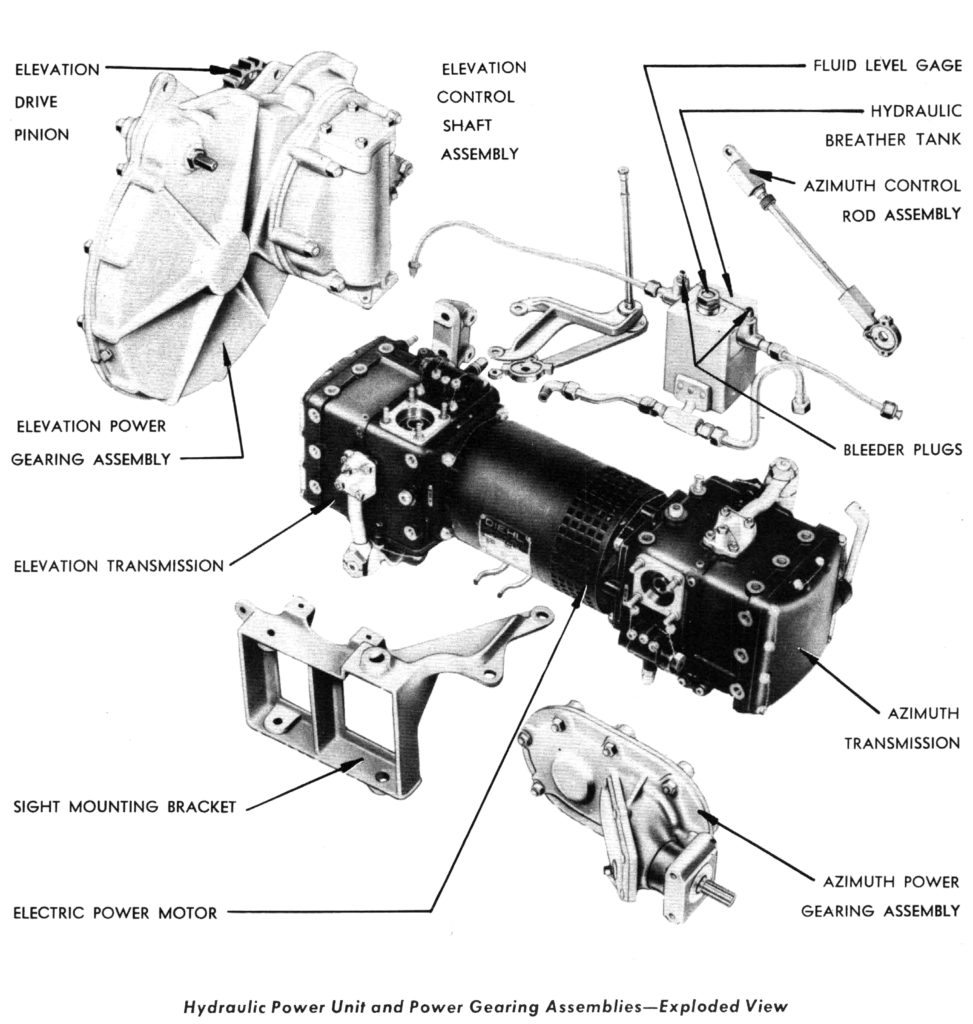

A manual page illustrating the various parts to the Ball Turret’s power unit assembly. The sight mounting bracket is center left.

We are still lacking manuals to the early-variant A-1 Upper and A-2 Lower Turrets. If you have these manuals and can share or scan them, please let us know! We intend to soon begin rebuilding Lucky Thirteen turrets, so anything and everything that can help us in this goal will be greatly appreciated.

Photo taken 7 May 2019.

A fascinating donation from Kyle Ulrey – a HAM radio operator specializing in the restoration of antique radios.

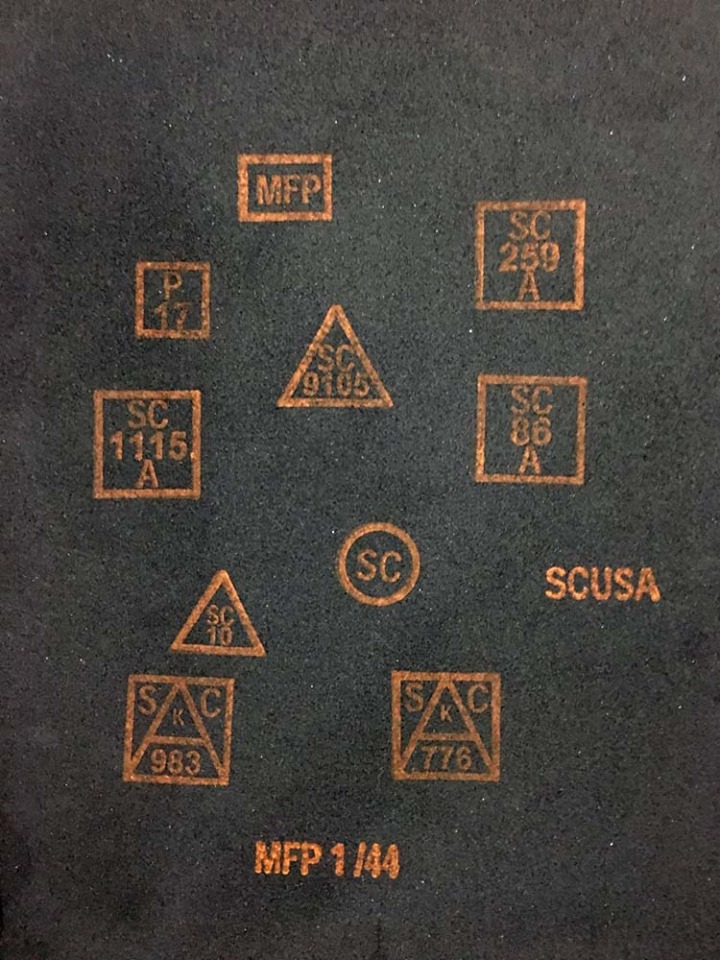

Several years ago, Kyle produced a limited series of rubber stamps for use in Second World War radio restoration. You see, Army Air Forces radio equipment was handled through the Army Signal Corps, who were required to inspect and approve each piece. Since several of the radios we are working with will require varying degrees of refinishing, we did not want to lose these period markings.

Kyle’s grandfather was a crewman on Nov Shmoz Ka Pop (44-8332, 487BG), and Kyle graciously donated a stamp set in his honor. I took the time to take Kyle’s stamps and mount them to wood blocks (to make handling easier) and test them out. They work great. Thanks Kyle!

Photo taken 7 May 2019.

The replica Signal Corps inspection stamps are tested. The resemblance to the originals is uncanny.

A 91BG radio operator uses the telegraph key in an early-B-17F. The Signal Corps inspection stamp on his BC-348 Liaison Receiver is highlighted.

The B-17G on which Kyle Ulrey’s grandfather served: Nov Shmoz Ka Pop (44-8332, 487BG).

The name comes from the Gene Ahern comic Squirrel Cage (1936 to 1953), whose Little Hitchhiker character would utter this non-nonsensical phrase.

Photo taken 13 April 2019.

This Hughes .50 Caliber ammunition chute was donated to us by Republic Air Salvage of Texas. We were looking to begin work on the wooden ammunition boxes for Lucky Thirteen and wanted to have at least one chute to ensure proper fitting.

Lucky Thirteen will need a host of ammo chutes in both left and right-hand varieties. Feed directions were indicated by the colored bands on each end: green for right-hand, red for left-hand, the color indicating which side of the gun the chute connects to. With this donation, we now have a right-hand 60 inch chute.

If anyone has chutes they can spare for Lucky Thirteen, please let us know!