Happy New Year everybody!

Here is a Christmas present Hangar Thirteen got all the way from Australia. Yes Australia, where AC/DC first cranked out their brand of blues-based rock, and Crocodile Dundee saved Linda Kozlowski from that swimsuit hungry crocodile. Many of you may know Dom Serong, who has an incredible collection of wartime navigation and bombing equipment which he has lovingly restored to operational condition.

Exactly the sort of quality and attention to detail that we wish to emulate in our work.

Well, Dom reached out to us some months back offering the correct autopilot control box for a late-F in exchange for help locating a rare switch. Thanks to our friend Steve Hester, we were able to make that happen!

The panel Dom sent us is a Type A-6A Autopilot Control Box made by Honeywell’s Minneapolis division (a former heat regulator company) for the B-17’s Type C-1 Autopilot System. This panel is practically new as it was NOS when Dom acquired it and only used afterward in his autopilot display. (If any of you have not seen it yet, we recommend you check out a demonstration of Dom’s autopilot, connected to a B-24 bombardier panel, on our Facebook Videos page.)

The C-1 autopilot functioned thusly:

An electric gyro located under the floor of the cockpit was connected to three servos through which the cables for each of the airplane’s control axis ran through. An amplified system, controlled by this panel (located in the cockpit), allowed the gyro to hold the airplane level when activated. This setup was also connected to a stabilizer underneath the Norden bombsight, allowing the bombsight to determine the aircraft’s course. As such, the autopilot was able to maintain the aircraft’s course and altitude for the mechanical computer inside the bombsight, dropping the bombs automatically when it calculated timing was correct to hit the optically aligned target.

In 1944 this system was supplemented by a pair of joysticks beside the pilots and a control panel that was modified to accommodate them. Called ‘formation sticks,’ these allowed the pilots to make small course corrections whenever necessary. Dom has examples of these and plans on adding them to his display. The switch we got for him was the switch that activates these joysticks.

Before we can start setting up our own autopilot display, there are some things we have to do. Our autopilot amplifier box is missing its cover and top piece, so they will have to be replicated. (Dom has graciously provided the measurements for these pieces.) Next, we will have to either locate or replicate the junction box for the autopilot’s electrics. We will also have to acquire one more servo. But the most difficult bit will be the bombsight stabilizer.

We had hoped that, by sharing the stabilizer we recently acquired from Canada, that it would be possible to replace the missing pieces and restore this unit. But so far, we have not had any luck finding anyone with the missing bits. A complete unit was offered to us down in Florida, but the price was unaffordable to us at $3,000. So, who knows what the future holds? But if we can acquire a complete bombsight stabilizer, that would complete the most difficult piece left for the autopilot, and Andy Rivera has a beautiful bombsight head that he’s ready to mount to it when the time comes.

Dom’s newly arrived Type A-6A Autopilot Control Panel.

When it arrived, I heard a didgeridoo at my back door. I opened to look and there sat a box of tea wrapped in crocodile skin.

Photos do not do it justice, it really is pristine.

Photo taken 27 December 2021.

Dom’s newly arrived Type A-6A Autopilot Control Panel.

The hole in the back is for the wiring to pass through.

Photo taken 27 December 2021.

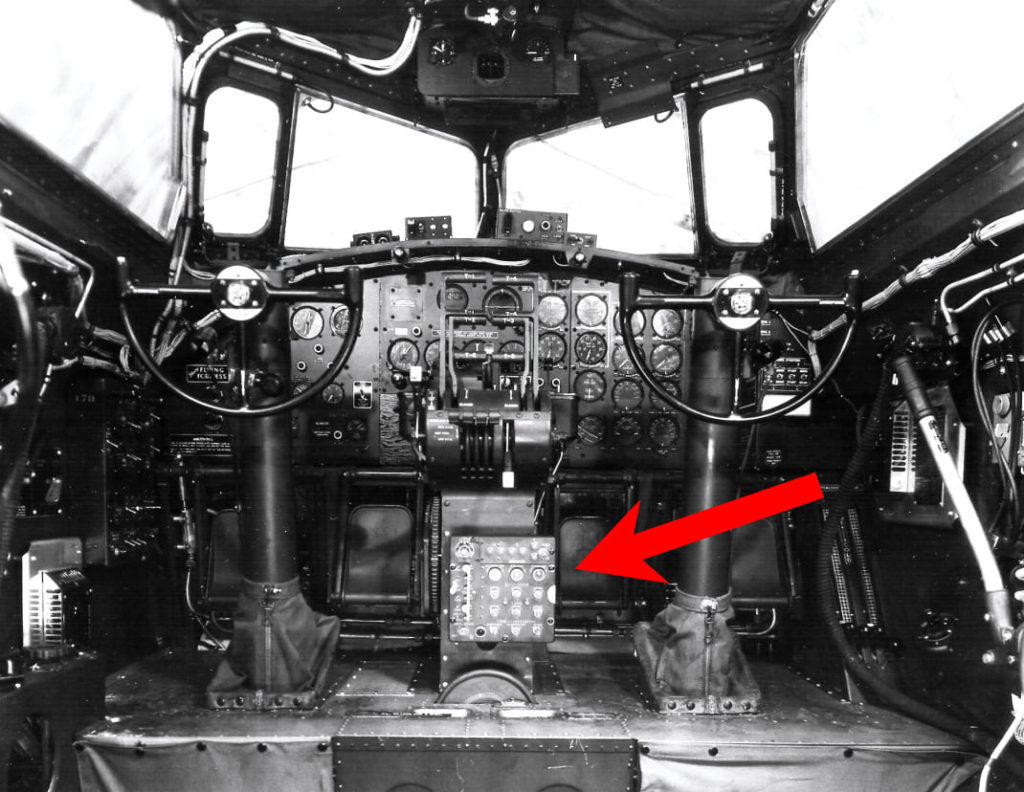

The Type A-6A Autopilot Control Panel is highlighted in this photo taken in the cockpit of a G-model B-17.

The seats have been removed for the photographer.

Note the control column boots. Chris Ely has offered to help us with these, and Bob Hachmann has fabricated the clamps that go on them. Once the clamps are painted, we can send all the materials to Chris.

A chart showing our current progress in gathering pieces to the Type C-1 Autopilot System.

We are looking to fabricate a new junction box (bottom) and the missing top and side-cover for the amplifier (left).

We still need to acquire one more servo and a complete bombsight stabilizer.

A photo of the Type A-6A Autopilot Control Panel while it was still at Dom’s place. This photo is taken with a UV light to highlight the original fluorescent markings.

Note the green tips on the switches – those were made with radium-laced phosphorescent paint, sealed in glass.

Photo taken 21 November 2021.

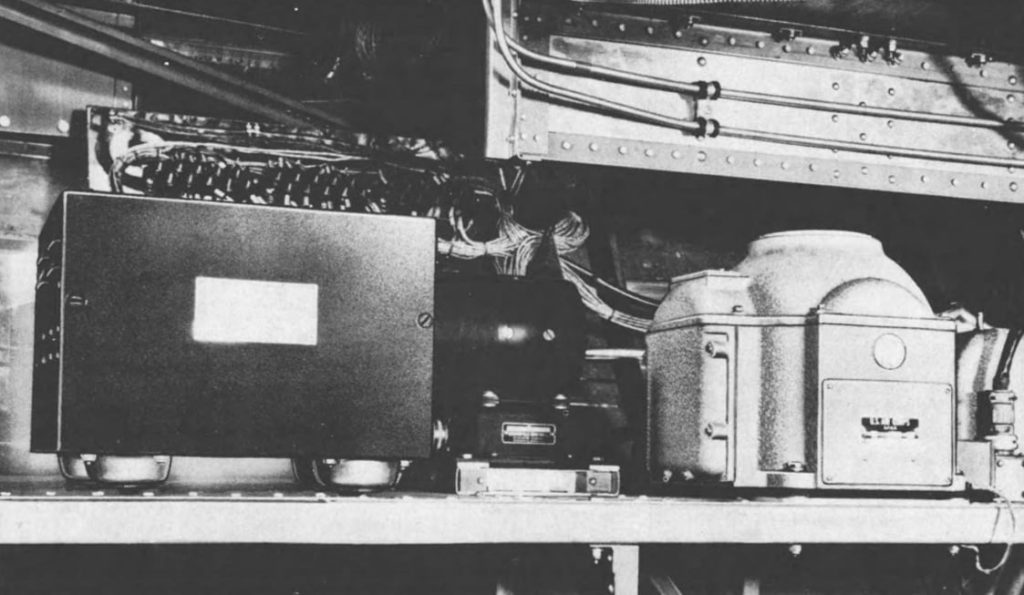

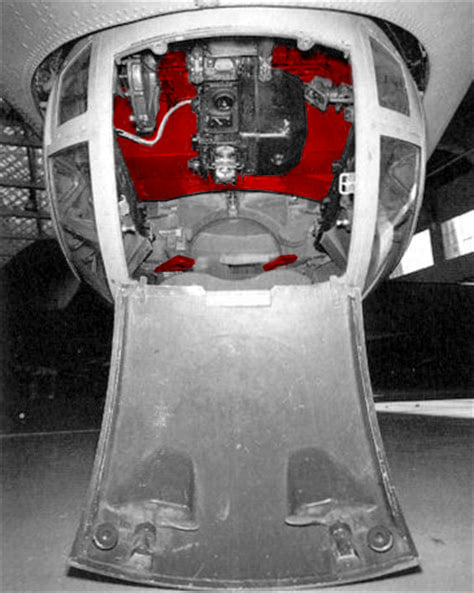

Under the cockpit floor sits (from left to right) the autopilot amplifier, inverter, and gyroscope.

The inverter in this illustration is an Eicor type.

The junction box is visible behind this equipment, with its cover removed.

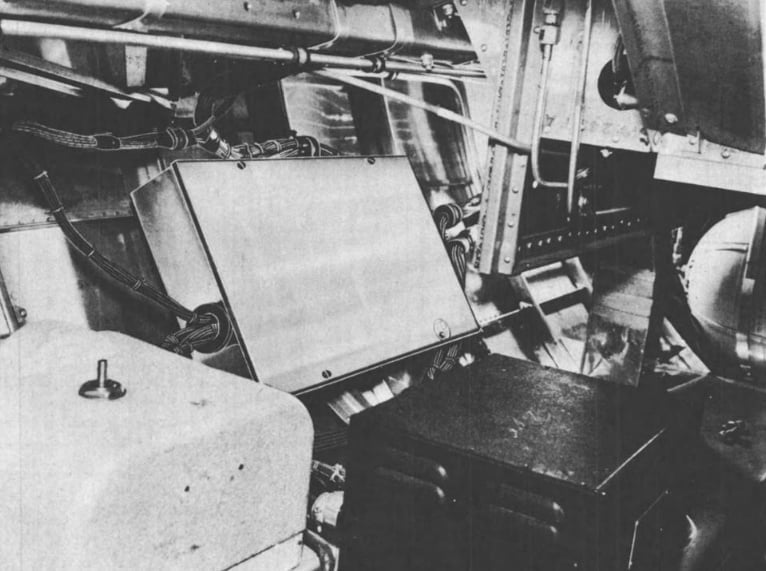

Another view of the autopilot equipment under the cockpit floor.

Here you can see the aileron servo (bottom left) and the junction box, which is mounted to the wall behind the amplifier.

On a shelf hanging over the tailwheel sits two of the autopilot servos, pulling the cables to the elevator and rudder.

One of the first photographs of the Norden bombsight shown to the public, released on 17 November 1944.

Note how the bombsight mounts to the stabilizer below.

Today’s update concerns a wonderful donation sent to us by John Atkinson of Newaygo, New Mexico.

John learned about us on the forums at WW2Aircraft.net and wanted to thank us for taking the time to scan and upload the various PDFs hosted on the Library page of our website. As such, he donated a Type G-1 oxygen tank and a set of six rare indicator jewel lights.

This tank brings us one step closer to outfitting the oxygen system for Lucky Thirteen. While oxygen tanks and bottles are not as rare as most pieces, that has not stopped their prices from rising as the years go by. And that hurts, as the Boeing B-17F carried a staggering 18 Type G-1 oxygen tanks, 2 Type F-1 oxygen tanks, and 13 Type A-4 walkaround bottles. These are readily found on eBay, CraigsList, and various antique stores so, if you manage to buy one for a good price, we can certainly recommend a good home!

John’s donation completes all of our instrument panel lighting needs except for a handful of dimmer lights. There were a great many Amber-colored dimmer lights scattered throughout the airplane, and we have gathered a fair amount so far, but the more pressing need are the Green colored ones.

I might add that Anton has recently completed something for us that is absolutely jaw-dropping in its complexity. He did a magnificent job and I cannot wait to share it with everyone – but I think we will wait until it gets here first…

Lastly, on a more unusual note, I was recently able to track down some surplus wartime webbing for the airplane. There were a plethora of little straps onboard in both .75 and 1 inch widths, so it is nice to finally have rolls of this material rather than having to waste money buying pieces yard by yard. To celebrate the occasion, I worked on the straps for the Flare Gun Stowage Shelf. Following blueprint spec, lift-the-dot fasteners were installed and the ends of each strap were dipped in bee’s wax. This project never ceases to surprise in where it ends up taking me…

John’s newly-donated Jeweled Indicator Lights.

For our serial number, theses were used for the Oil Pressure Main System, the Oil Pressure Emergency System, and the Vacuum.

Photo taken 9 December 2021.

John’s newly-donated Type G-1 Oxygen Tank.

These were often converted postwar into portable air bubbles for flat tires. In John’s case, it was part of a home-made air compressor.

Photo taken 9 December 2021

T/4 Clifford Coates recharges the oxygen system of a 466BG B-24. The tank in his hand is a Type G-1.

The bottles at his feet are Type D-2 walkaround bottles. The D-2 was the third of four USAAF walkaround bottles used during the war: the A-2 (the sole constant flow unit), A-4, D-2, and A-6. The A-6 continued to see use into the Korean War and early years of Vietnam. While the A-4 and A-6 could be clipped to the airman’s jacket, the A-2 and D-2 required

The D-2 replaced the A-4 in 1944 because of the A-4’s small size.

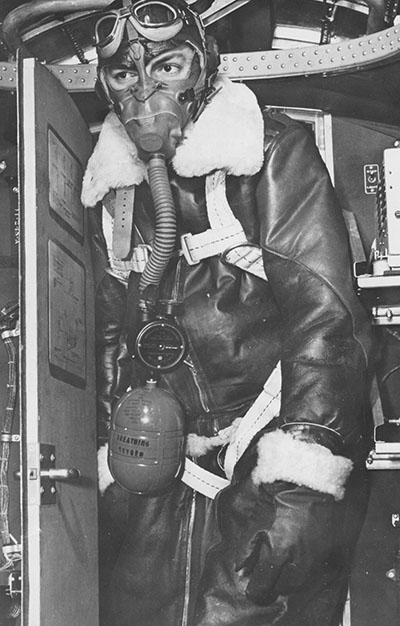

An airmen walks through the forward radio door of a late-B-17F. His Type A-10 mask is connected to a Type A-4 Walkaround Bottle. Both the aircraft and the equipment worn here is also accurate for Lucky Thirteen.

The term “A-4” is actually in reference to the bottle itself, as the regulator for this unit is a Type A-13. Hooked together, the formal designation is AN6020-1.

Another unidentified airman, carrying a Type A-4 walkaround bottle through the bomb bay of a B-17G. Judging by his clothing, this was taken sometime in 1944.

Note his bottle does not have any bands around it. This feature of A-4 bottles varied depending on manufacturer.

The newly-arrived rolls of .75″ and 1″ wartime surplus cotton webbing.

Photo taken 11 December 2021.

After hours of cutting and some bloody fingers, the lift-the-dot fasteners are installed and the straps ready for dipping.

Photo taken 3 December 2021.

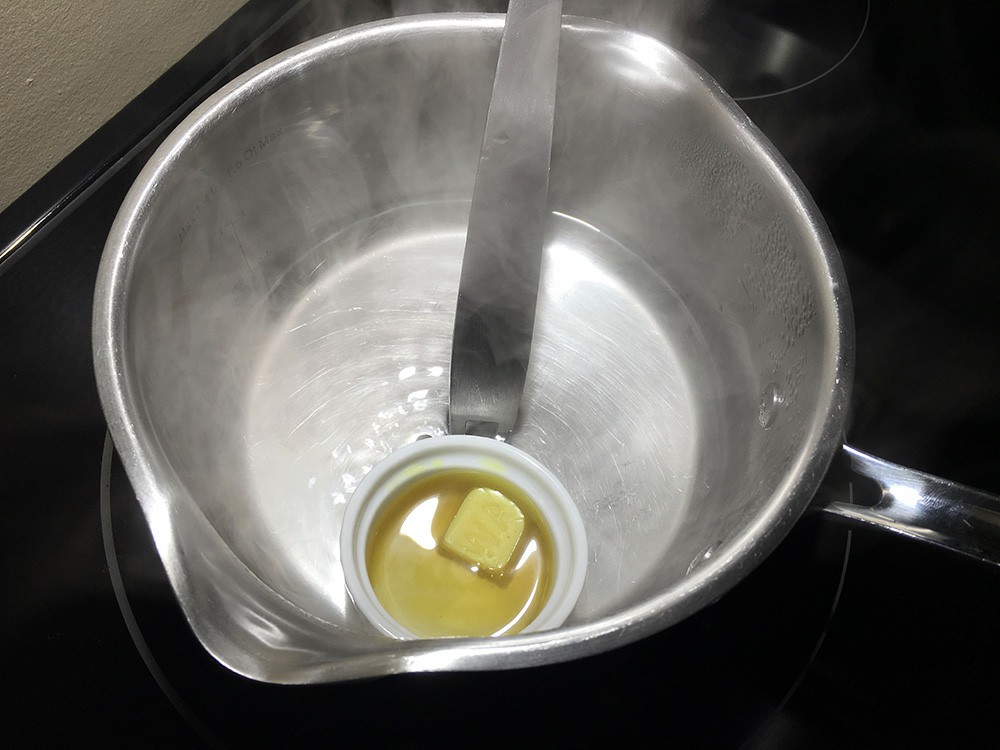

Melting the bee’s wax for dipping.

Photo taken 3 December 2021.

The straps for the flare container are ready to be installed.

These straps are stapled to the shelf, wrapping around the flare container and clipping to its sides.

Photo taken 3 December 2021.

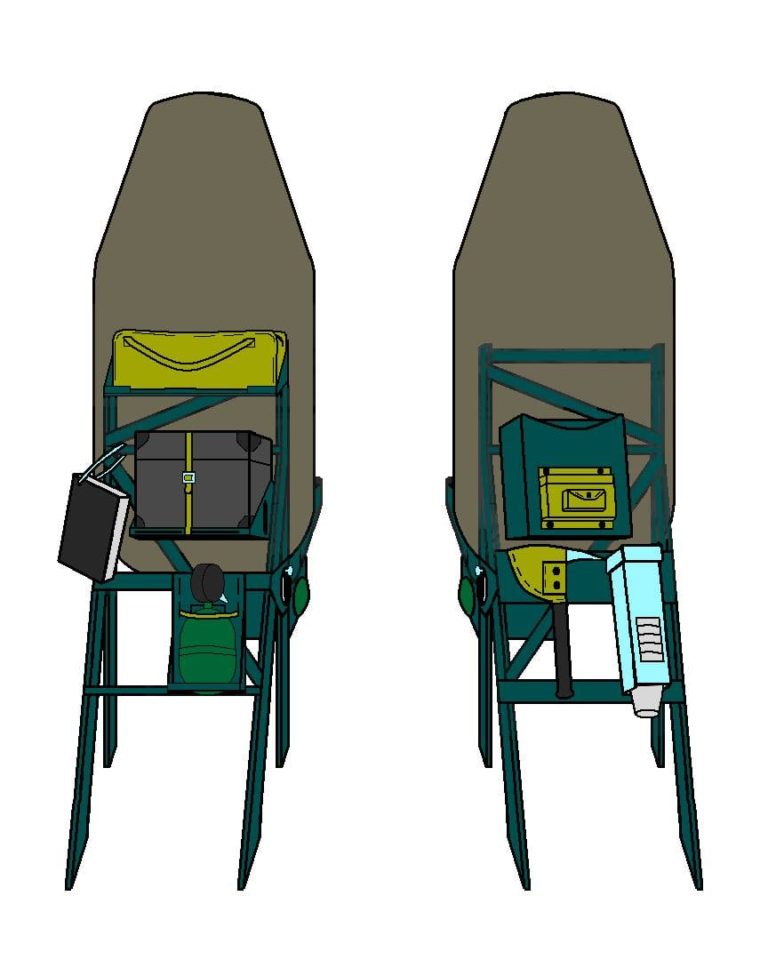

A drawing we created showing the layout of the pilot seats aboard Lucky Thirteen.

The flare gun equipment is located on a small shelf on the pilot’s seat (left). Also on this seat is the Aldis Lamp, a pair of A-4 walkaround oxygen bottles (pilot and engineer), an ashtray, and the aircraft’s familiarization manual.

The co-pilot’s seat carries the Wiring Diagram Box, a First Aid Kit, an ashtray, another A-4 walkaround oxygen bottle, the Crash Axe, and the Cup Dispenser for the aircraft’s thermoses.

Before beginning, we would like to give a special thanks to everyone who responded to our request for donations back in November/December of 2021.

David Cohen

Keith Ellefson

Hubert Figueiredo

Joe Hall

Karl Hauffe

Aaron Hollander

Chris Hrabina

George Hunt

Shawn Hutson

David Mitchell

Thomas Perry

Don Price

Thank you SO much!

We were given an opportunity to visit a parts warehouse in Florida and these guys stepped forward to ensure we would be able to do so.

That part of Florida is roughly an 8-hour drive for us, meaning it had to be an overnight trip. Unfortunately, we were not able to find any B-17 components while there.

But no worries – donations are ALWAYS needed! Various projects currently needing funding are the C-1 autopilot, ammunition chutes, cockpit instruments, and power turret components (the biggest financial drain of them all). If you would like to donate like the guys noted here, just visit our donate page!

Some highlights from the trip:

A pair of Type K-25 cameras donated to us by Keith Ellefson of Ozark, Alabama.

The K-25 was a small, electrically operated camera designed for low-altitude reconnaissance platforms like converted fighters and ground-attack aircraft.

We passed by Keith’s home on the way down and Keith offered to buy us lunch. Thanks Keith!

Photo taken 14 November 2021.

Boeing B-17G 44-83863 on display at the USAF Armament Museum beside Eglin AFB.

Despite her Army markings, this B-17 is actually a Navy PB-1, seeing postwar service as a fire-fighting air tanker. Ironically, the National Naval Aviation Museum is just down the road in Pensacola.

The PB-1’s role in naval history is actually quite important, operating through Project CADILLAC as one of history’s first airborne warning and control (AWACS) aircraft. Sadly, the Navy has traditionally shown little interest in preserving large aircraft. You can read more about the PB-1W in our B-17 Oddballs update.

Photo taken 13 November 2021.

The ball turret on Boeing B-17G/PB-1 44-83863 on display at the USAF Armament Museum beside Eglin AFB.

Note the lack of a lower windows on the front of the ball and the small number of windows on the ball’s sides. This indicates that this ball came from either a Type A-2B or Type A-13A ball turret. The A-2B was designed for the B-17G and the A-13A for the Consolidated B-24N and B-32 Dominator. While the A-13A saw limited service in 1945, the A-2B never entered full-scale production.

Photo taken 13 November 2021.

Boeing B-52G El Lobo II (58-0185, 2BW) on display at the USAF Armament Museum beside Eglin AFB. This aircraft was named after a late-B-17F like Lucky Thirteen – El Lobo (42-30249, 384BG), which was lost on 30 December 1943.

El Lobo II is one of the most historically important aircraft on display at this museum. On 16 January 1991, she participated in Operation SENIOR SURPRISE – the first Coalition airstrike of Operation DESERT STORM. The US 8AF launched seven B-52s from Barksdale AFB, Louisiana against hydroelectric and communication centers in Mosul, Musayyib, and Basra, Iraq, covering some 14,000 miles in 34 hours, 30 minutes. This was the first airstrike ever launched from the continental United States. The bombers launched 35 ACM-86C cruise missiles, each carrying a 3,000 lb warhead and guided to the target via GPS (another first).

Known as “Secret Squirrel” amongst crews, there are only two participants of this strike still with us today: El Lobo II and Valkyrie (58-0183), on outdoor display at the Pima Air & Space Museum in Tucson, Arizona.

Judging from her appearance, El Lobo II is soon to be repainted.

Photo taken 13 November 2021

The tail gun assembly aboard Boeing B-52G El Lobo II (58-0185, 2BW), on display at the USAF Armament Museum beside Eglin AFB.

DESERT STORM saw the last use of American bombers equipped with tail gunners. On 17 January 1991, B-52G Midnight Rendezvous (58-0248, 4300BW) was heavily damaged when an F-4 WILD WEASEL fired an AGM-88 HARM missile at an Iraqi AAA position. To everyone’s horror, the missile tracked the fire control system for the B-52’s tail gun instead. The bomber was successfully repaired and renamed In HARM’s Way.

Though no official relation has ever been admitted, it is generally believed that this incident helped prompt the removal of all US tail turrets the following year.

Photo taken 13 November 2021.

The sad remains of a CIM-10 BOMARC surface-to-air missile on display at the USAF Armament Museum beside Eglin AFB.

The Boeing Michigan Aeronautical Research Center CIM-10 was developed as part of a series of postwar projects to design surface-to-air missiles. The first successful US SAM was the MIM-3 Ajax of Project NIKE, first tested on 27 November 1951. The BOMARC was a longer-ranged design and was first tested off the coast of Florida on 23 October 1957. Both of these tests used surplus B-17s as target drones.

Photo taken 13 November 2021.

A GBU-43 Massive Ordnance Air Blast bomb on display at the USAF Armament Museum beside Eglin AFB.

The MOAB is sometimes called the “Mother of All Bombs” because it is supposedly history’s largest conventional explosive. Pushed out the back of a Lockheed C-130, the bomb weighs some 21,600 lbs, 18,700 of which comprises explosive material. The MOAB has only been used once in combat, being dropped over Afghanistan on 13 April 2017 against an ISIS cave complex.

The US lacked a conventional bomb larger than 4,000 lbs during the Second World War. The RAF were more successful, their heaviest bomb being the 22,000 lb “Grand Slam.” Though technically heavier than MOAB, the Grand Slam’s explosive weight was actually 9,500 lbs, requiring a heavy steel casing so it could penetrate the ground before detonation.

Photo taken 13 November 2021.

Eglin AFB is particularly well-known for two things – being the training ground for the Doolittle Raiders and for being the home of Air Force Special Operations Command. Based at Hurlburt Field, AFSOC is the home of the Lockheed AC-130 Spectre gunship. We could see them on the flight line as we drove by!

A product of the Vietnam War, Project GUNSHIP saw the conversion of cargo aircraft into airborne firebases, mounting a variety of guns to one side and performing slow pylon turns over targeted positions (usually in the relative safety of night). This particular AC-130, First Lady (53-3129), is the oldest one still in existence, being a Vietnam veteran who was retired after an AAA hit on 25 March 1971. She is on outdoor display at the USAF Armament Museum beside Eglin AFB.

The AC-130 was preceded in service by the WWII-era Douglas AC-47 Spooky and Korean-war era Fairchild AC-119 Shadow/Stinger. No AC-47s or AC-119s still survive, though there are multiple C-47s altered to look like gunships.

Photo taken 13 November 2021.

For Thanksgiving 2021, we posted the following on Facebook:

This Thursday is Thanksgiving, a tradition-turned-holiday that originated with the first European immigrants to North America. They thanked God for getting them through the hardships of those early days, and in homage to that, the holiday is likewise meant to be a time of reflection. Many families observe the custom of vocally listing the things for which they are thankful. And while some may find it a bit cheesy, I thought we at Hangar Thirteen might do the same.

We are thankful to Orville and Wilbur Wright, whose blue-collar ethos gave birth to modern aviation with a homemade engine on wings of fabric and string.

We are thankful to Bill Boeing, who created an aircraft company in 1916 that, by the mid-20th century, had a reputation for excellence so unquestionable that today’s industry can hardly begin to comprehend.

We are thankful for Ed Wells, who at age 24 chaired the engineering team that designed the B-17, and for encouraging other engineers like George Schairer to never stop improving upon it.

We are thankful for Henry Stimson who, despite political differences with FDR, carefully managed the American war effort with a skill never seen before and never seen again.

We are thankful for the multitude of companies who set aside their rivalries to produce not only components for the B-17, but in some cases even create B-17s themselves.

We are thankful for the untold thousands of men and women who worked in these plants to create parts and components. George Patton’s words proved prophetic when he said that ‘a pint of sweat can save a gallon of blood.’

We are thankful for the Army officers who conceived of the American strategic bombing campaigns in an attempt to shorten war and save the lives of its combatants.

We are thankful for those commanders who adapted these concepts to fit the realities of war, and who endured the mental anguish of knowing that their decisions required sacrificing the very people they cared for.

We are thankful for the men and women of our wartime allies, who not only fought side-by-side with us but played host to our people with a graciousness that has never been forgotten.

We are thankful for our veterans. It is to you that we pledge our commitment to remembrance. It is our greatest hope that our work makes you proud and rekindles memories long faded.

We are thankful for those servicemen who fought and died in history’s greatest confrontation. Your sacrifice will never be forgotten. May our efforts do your experiences justice.

We are thankful for the families of servicemen. We hope that our works connect you to the past as much as your stories do for us. For many, history is little more than a picture in a book, but for you this is real.

We are thankful for the various odd jobs that the warbirds of yesteryear found in peacetime. Without them, much of what remains with us today would be lost.

We are thankful for the historians, researchers, and archivists who over the years preserved wartime documents so that we can reference them. The amount of detail one can pull from the most innocuous of photos, or the driest of reports, is at times staggering.

We are thankful for our friends in the historic preservation/restoration community. Be you collectors, tinkerers, airplane nuts, etc., we all share the same goal, and these last few years have created friendships that are quite dear to us.

We are thankful for our followers. Sometimes the simplest comment can brighten our day and rekindle the flame when things get tough.

We are thankful for our donors. Hangar Thirteen has no wealthy benefactor and asking for help does not come easy to people like us. Your selfless donation of parts and funds helps more than words can express.

And lastly, we are thankful for our volunteers. Rebuilding a B-17 is hard work – doing it accurately, doubly so. We applaud you going the extra distance to rebuild and/or restore components normally overlooked, with light, sound, and moving parts bringing history back to life in a way that no other approach can do. Without you this project would simply be impossible. If we are to succeed in this endeavor, it is to you that the laurels of success should be bestowed.

Happy Thanksgiving everybody.

Keep the show on the road.

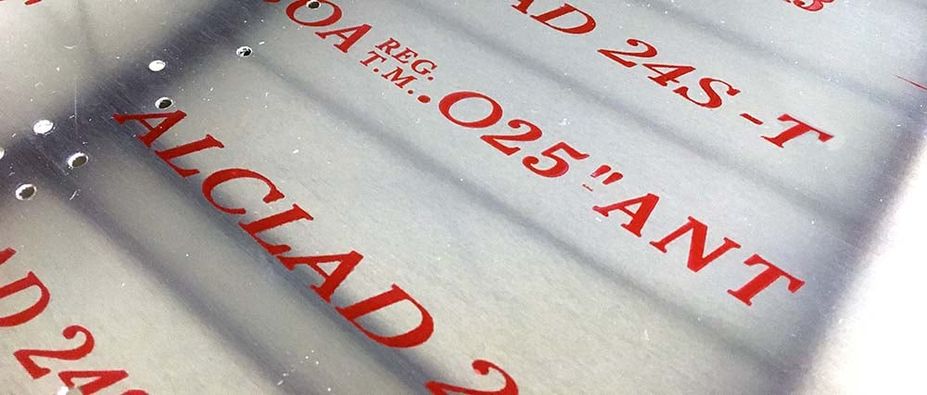

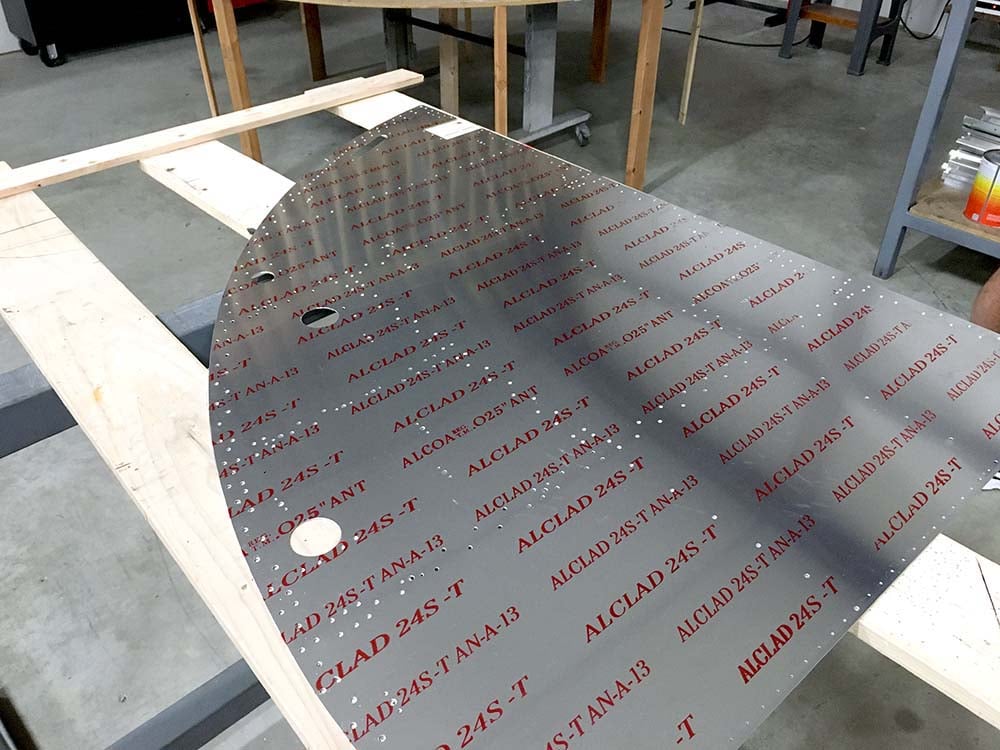

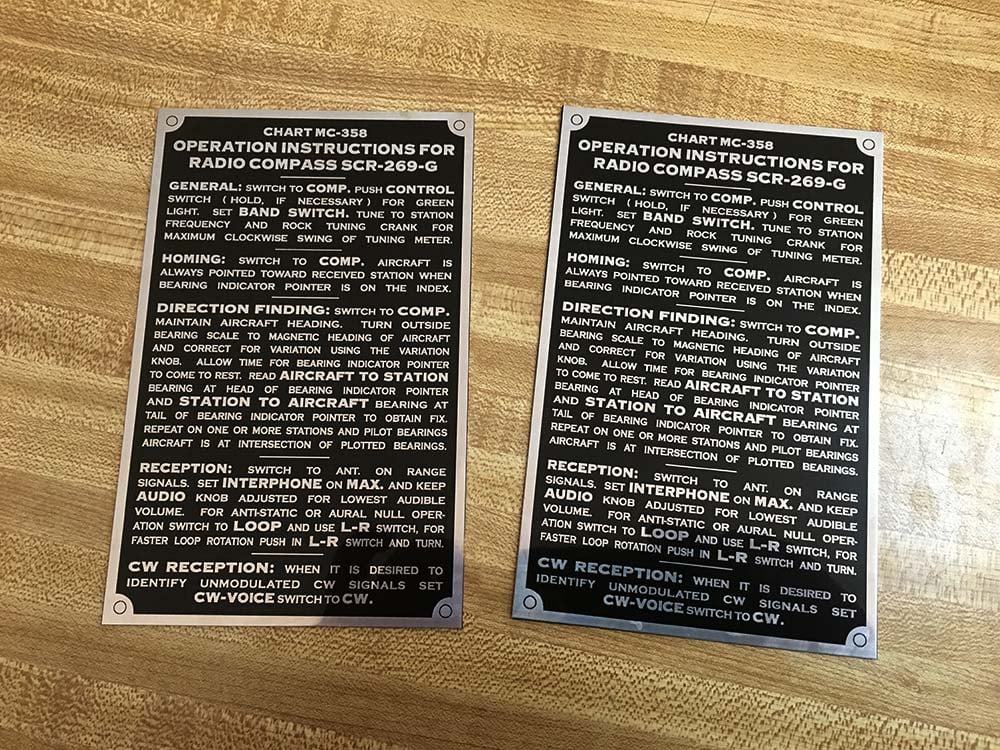

Some of you might recall that my wife Megan S. Blume is a graphic artist. She has been an incredible asset, recreating old logos, markings, and documents. Lately some of her work has been front and center. For example, we recently recreated a pair of MC-358 instruction plates for the SCR-269 RDF system on the Warbirds Of Glory Museum‘s B-25J “Sandbar Mitchell.” A pair of these plates were also recreated for Memphis Belle back in 2019. Perhaps her most visible contribution has been in scanning and recreating the ALCLAD markings visible on wartime aircraft aluminum. Since the B-17’s interior was largely unpainted, recreating these markings is a huge step forward toward true fidelity. Recently we applied these markings to the skins for Station 5 (the forward wall of the radio compartment) on Lucky Thirteen. These skins are now ready to be permanently riveted in place.

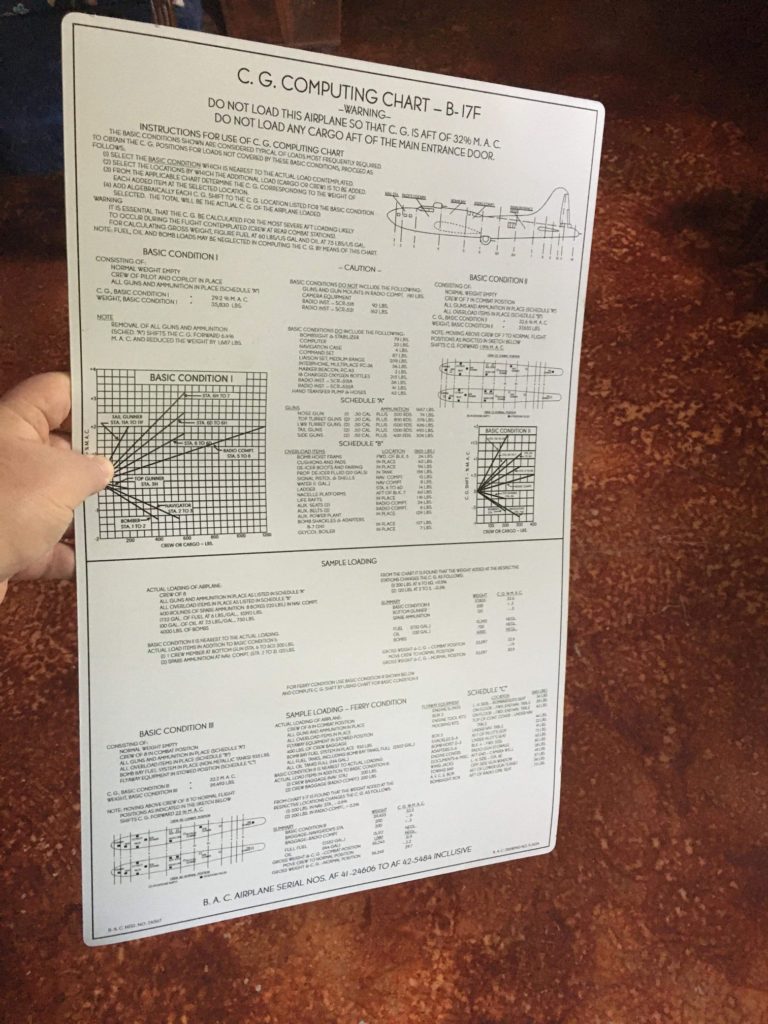

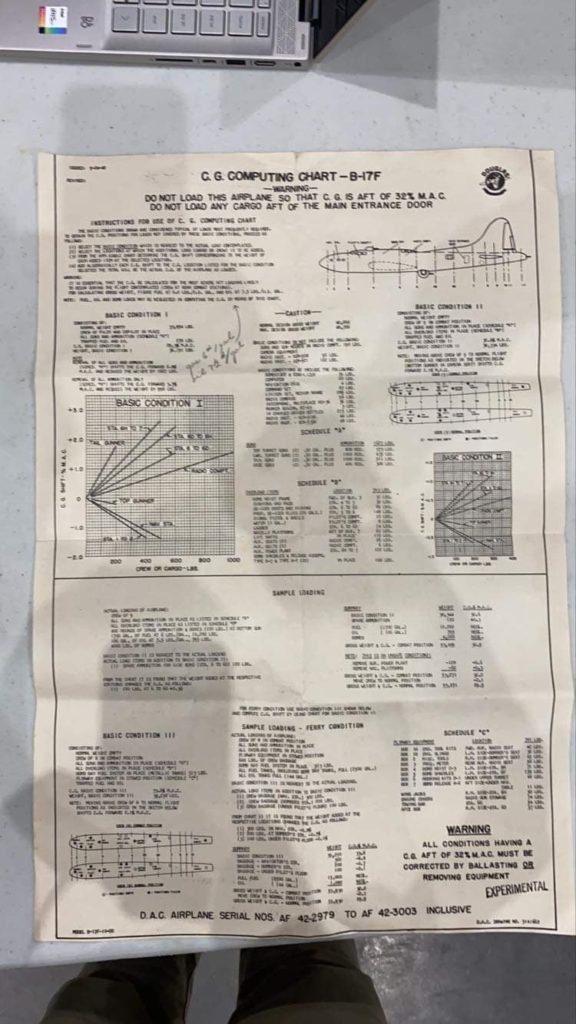

Speaking of the Belle, you may recall that we recreated her interior chartage. As the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force has begun to release photos and video clips of her interior (which is still incomplete), some of these charts have been visible. For me, seeing my work in the actual Memphis Belle is true honor. The largest of these charts was the CG (Center of Gravity) Computing Chart, which was mounted on the inside of the Station 5 door. Our friend Dave at the B-17 Cockpit Project recently found an original one of these, so it was fun seeing how close we got by following the blueprints.

These CG Computing Charts were eventually replaced by a pamphlet kept in the back of the B-17F’s Familiarization Manual for Operations. This was one of two Familiarization Manuals that came standard on all F-model B-17s, the other being for Maintenance. Because of collectors, these manuals tend to be rather expensive, so we do not yet have a pair for Lucky Thirteen. However, a gentleman from Pennsylvania did recently loan a pair for scanning. Since the Maintenance manual is over 600 pages and already on Air Corps Library, we only scanned the Operations manual. It is now on the Library page of our website.

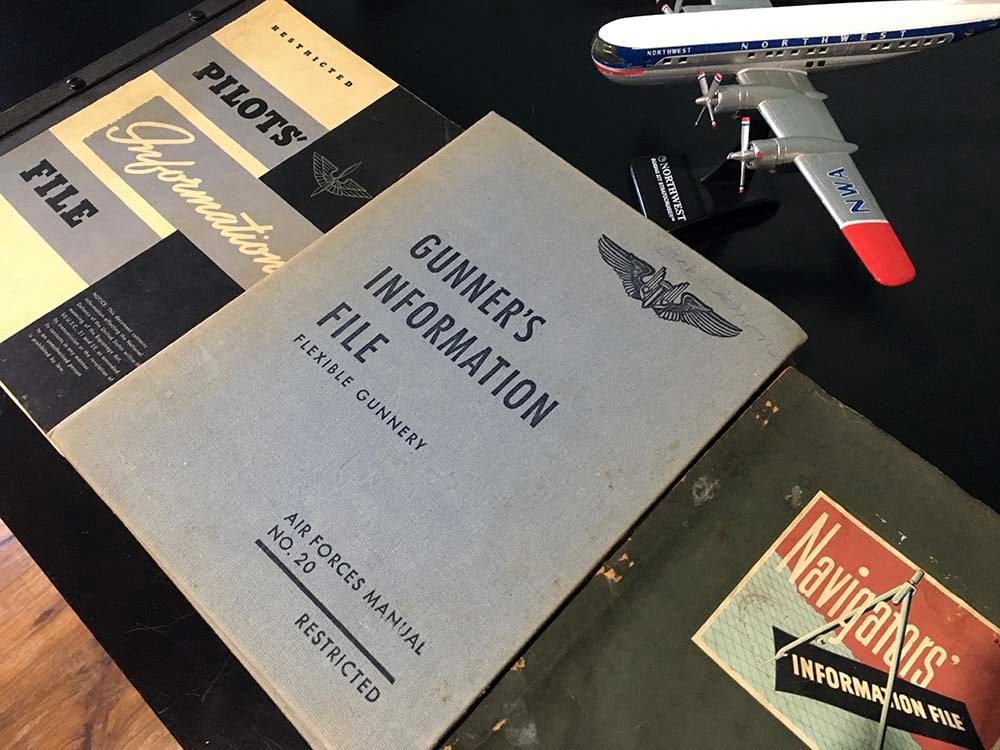

Similarly, in our quest to acquire an example of each crew stations’ Information File, we recently acquired original examples of the Navigator’s and Aerial Gunner’s Information File. These two have also been scanned, cleaned, and placed on the Library page of our website. With others having already scanned the Army Information Files for Pilots, Bombardiers, Radio Operators, and Radar Operators, we now have digital copies of every wartime Information File. However, we still do not have physical copies outside of the Pilot, Navigator, and Aerial Gunner.

A closeup of the ALCLAD markings applied to Station 5.

Photo taken 2 November 2021.

The ALCLAD markings applied to one of the two Station 5 skins.

Photo taken 2 November 2021.

The recreated MC-358 plates for the SCR-269 Radio Compass system on Sandbar Mitchell.

Picture taken 19 November 2021.

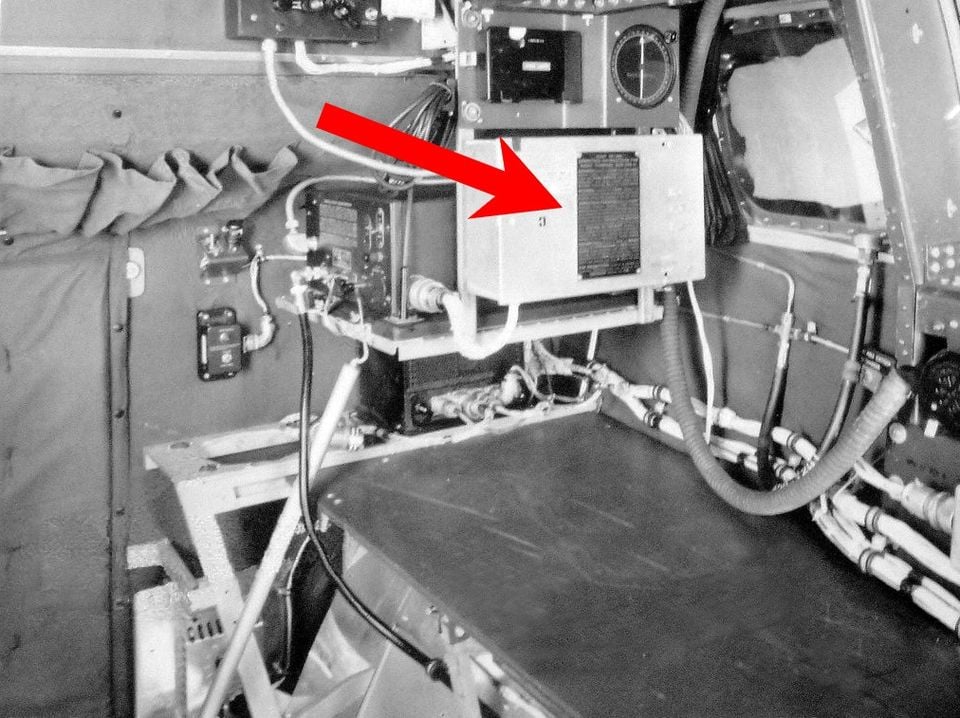

An MC-358 Operating Instructions plate for the SCR-269 Radio Compass, mounted to the left of the navigator’s position on a Boeing B-17F.

The navigator’s position on Lucky Thirteen will be almost identical to what you see here.

A prototype for the CG Computing Chart made for Memphis Belle. The finished product was made and sent some years back.

The wartime spec. cardstock used to recreate the charts on Memphis Belle and Lucky Thirteen was donated by Monadnock Paper Mills of Bennington, New Hampshire.

Photo taken 8 June 2021.

A wartime CG Computing Chart that Dave Littleton of B-17 Cockpit Project recently located, tucked away in the back of an old manual.

Interestingly, this one came from a Douglas-built aircraft.

Photo taken 8 June 2021.

TSGT Charles Melchiondo, radio operator on Invasion II (42-5070, 91BG). Note the CG Computing Chart behind him, which is peeling.

Invasion II was the aircraft originally chosen by William Wyler to be the subject of a documentary film. When Invasion II was lost over Bremen on 17 April 1943, he chose another aircraft: Memphis Belle (41-24485, 91BG).

An official National Museum of the U.S. Air Force photo of the interior on Memphis Belle. The CG Computing Chart is visible on the radio compartment door.

Note the green shelves to the left of the ball turret. These hold the B-17’s VHF radio. These radios are seldom seen even though they are for the prominent mast antenna above the tail.

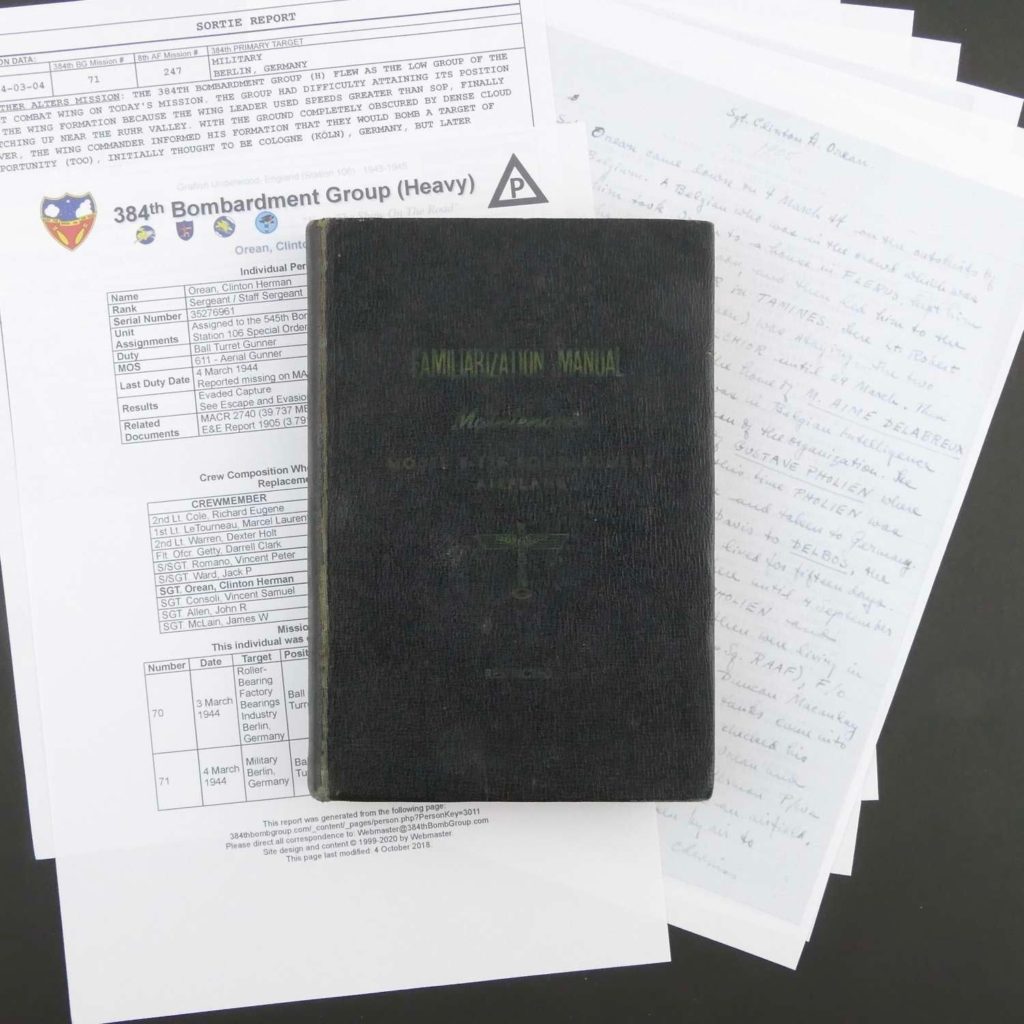

An image of a B-17F Familiarization Manual (Maintenance) borrowed from the Historic Flying Clothing Company. This particular example belonged to a 384BG veteran, SSGT Clinton H. Orean.

Every B-17F came with a Familiarization Manual (Operation), Familiarization Manual (Maintenance), and CG Slide Ruler specific to that particular aircraft.

The Information Files we have obtained for Lucky Thirteen so far.

All that is left are the Bombardier and Radio Operator’s Information Files.

Photo taken 7 December 2021.

You may recall that, back in July, we acquired sets of ball turret gun-charging handles from our friend Fred Bieser. Since it is our intention to do the ball as an early Brigg’s built model rather than an Emerson, our charging assemblies needed to be gray instead of green. Fred did not have two complete early Briggs sets, so we had to do some work.

Fred gave us a complete late-Briggs set, a complete Emerson set, and an early Briggs set that was missing its wire assembly. To get what we needed, we had to replace the plastic handle on the late-Briggs set with a wooden one and switch out the wire from the Emerson set to the early Briggs set. Since its handle was dry rotting, it needed to be replaced too.

The original handles were carefully measured, 3D modeled, and turned on the CNC machine. Special thanks to Legacy CNC for their help in this process! From there, the handles and assemblies were sent to Bob Hachmann in Iowa, who lovingly lacquered and installed the new handles, and switched out the wire assemblies. They look absolutely amazing – great job, Bob!

Bob also took the time to measure and 3D model the assemblies themselves. We had planned to 3D scan an early ball turret but the arrangement fell through, and since then, we have been working with the Smithsonian in the hopes of locating the original blueprints. Meanwhile we will try to clean and restore the pieces we have and, as donations come in, acquire what we can.

Speaking of handles, we recently sent Kevin Davenport our one original B-17 interior door handle. We have acquired a few handles over the years but, according to our research, only one of these was actually the real McCoy. Since we need a fair number of these, we needed a 3D model from which to make new molds. Kevin has successfully modeled the handle and has 3D printed a plastic replica for us to inspect. Looks spot on – great work, Kevin!

If you can help with turret parts, metal molding and casting, and/or would just like to volunteer, please do not hesitate to contact us!

The newly-restored Sperry (Briggs) A-2 Ball Turret gun charging handles.

Photo taken 11 December 2021.

The Ball Turret gun charging handles when we first acquired them.

While Sperry Gyroscope designed the Type A-1 Upper and A-2 Lower Turrets, they did not actually manufacture them. Instead, they were contracted out, with Steel Products Engineering of Springfield, Ohio producing the top turret and Briggs Manufacturing of Detroit, Michigan producing the ball turret. When these companies failed to meet expected production rates, both turrets were supplemented by Emerson Electric of Ferguson, Missouri.

The Emerson charging assembly is painted Dull Dark Green with red handles.

The Briggs charging assembly with the plastic handle is late-war, coming from a Type A-13A turret. There are many Type A-13As surviving today though, in reality, they only saw wartime use aboard the Consolidated B-32 Dominator. To backdate it, the plastic handle had to be replaced with a wooden one.

Photo taken 14 July 2021.

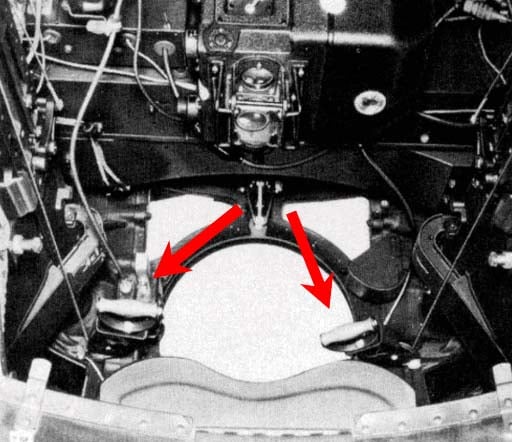

The gun charging handles are highlighted in this photo of an Emerson-built ball turret.

These handles were pulled whenever the guns required ‘cocking.’

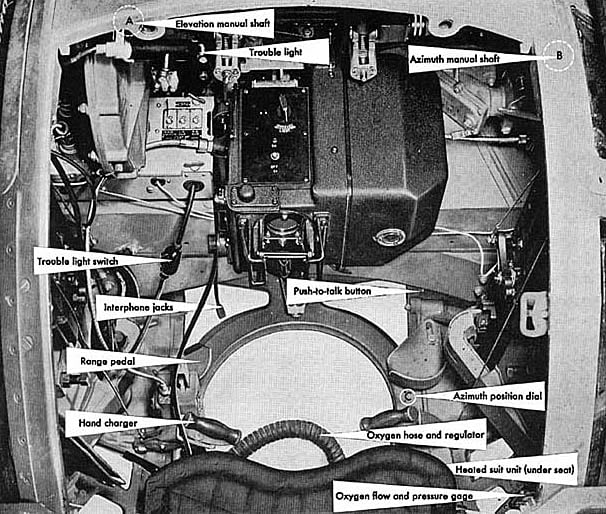

An annotated photo showing the interior of a Briggs-built ball turret.

Note the difference in color between this turret and the Emerson turret in the previous photo.

The blank is ready for turning. The wood is maple.

Photo taken 17 November 2021.

The first of the handles are turned on the CNC.

Photo taken 17 November 2021.

Our current progress on the Type A-2 ball turret for Lucky Thirteen is highlighted in red.

Strangely enough, it is easier to find parts for the ball turret than it is to find the actual body. The ball itself will have be cast anew.

The drive assembly is located at the top, with the elevation and azimuth connector gears on either side.

In front of this assembly, taking up most of the room, is the ball turret’s ammunition magazine. It is a common myth that the ball turret’s ammunition was fed through external cans. External fed ball turrets were a late-war development, primarily seeing service aboard the short-lived B-32 Dominator.

Though not shown, we also have one link ejection chute, a push to talk switch, and a position indicator gauge.

We are currently working on acquiring enough Edgewater adapters to outfit the entire aircraft. Likewise, we have the files ready to cut all the armor plating, only needing the appropriate metal (.25 thick stainless steel).

Kevin’s 3D printed door handle next to the wartime original.

Looks like he got the CAD model perfect – now to just have a set casted.

Photo taken 17 December 2021.

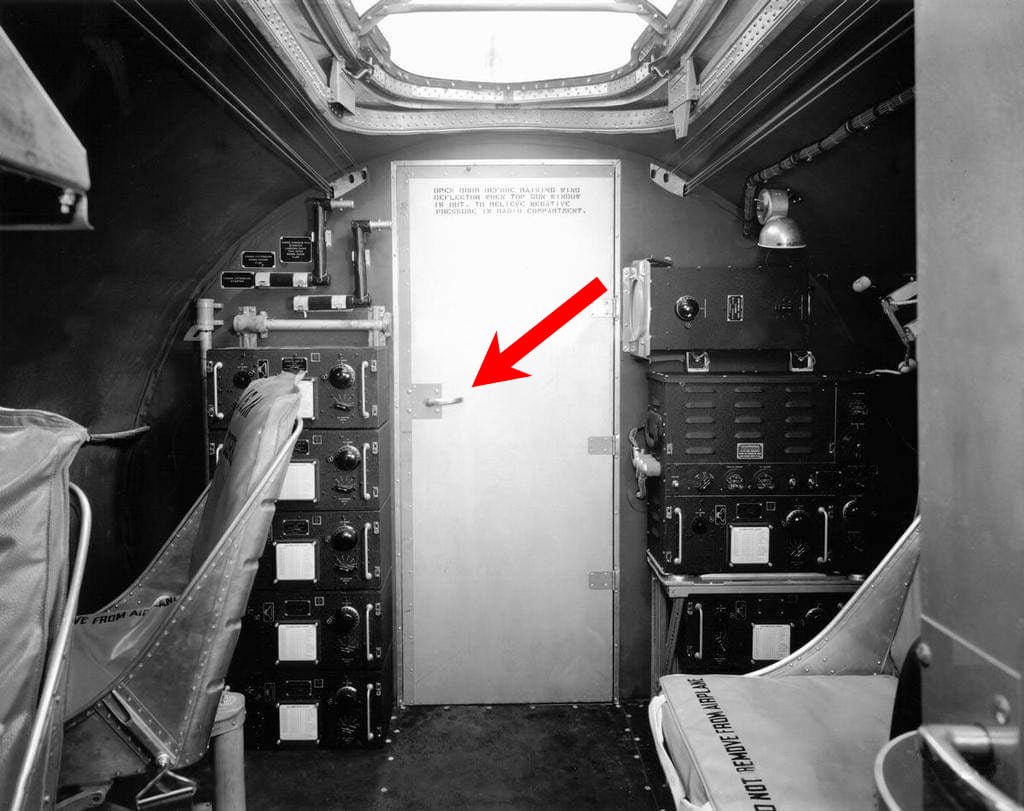

The door handle to Station 6 (the back wall of the radio compartment) is highlighted.