Boeing B-17C

The Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress is perhaps the most iconic military aircraft in American history. Featured in such films as Twelve O’Clock High (1949) and Memphis Belle (1990), the B-17’s clean lines are reminiscent of an age gone-by. While this aircraft’s beauty has inspired many over the years, we must never forget that this was a machine of war – a machine designed to kill. More-so, this was a machine in which young Americans themselves were killed, with more American airmen dying in the Second World War than sailors or Marines.

Designed in 1935, the B-17 was the first four-engine, all-metal monoplane aircraft accepted for use by the US military. Throughout its early years, the bomber was largely unwanted, the US government passing it in favor of smaller, cheaper aircraft. The only people who really wanted the B-17 were the Army Air Corps, who saw in it a future test-bed for their theories of daylight precision bombing. As such, they were able to obtain a trial version of thirteen aircraft, which they used constantly, until the signing of the Munich Agreement in September 1938.

Boeing B-17E

The failure of the Munich Agreement to secure peace in Europe spurred the Roosevelt administration, and the B-17 finally entered service as the primary bomber of the Army Air Forces. Production was at first slow, having only produced 138 when the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor on 7 December 1941. Many of these early B-17s, nicknamed “shark tails” for their distinctive shape, saw service with Great Britain, whose difficult combat experiences prompted Boeing to redesign the aircraft with the B-17E.

The E-model was the first of the heavily-armed B-17s. Sporting Browning M2 .50 caliber machine guns in flexible positions in the nose, radio room, waist, and tail, as well as powered turrets above and below, the new B-17s were veritable “flying fortresses.” This was necessary. Aircraft designers had still not solved the problem of long-range escort, the fuel tanks on fighter aircraft being too small to protect the bombers for the entire length of their journeys. If US bombers were going to bomb by daylight – as American air planners had hoped – they had to do so in formation, depending on one another for much of their protection.

B-17F Nose Modification

The US Eighth Air Force in England was the primary theater for B-17 usage, the bombers testing the prewar “industrial web” theory against Nazi Germany. Beginning on 17 August 1942 with strikes against coastal cities in occupied-Europe, losses grew over the months as the assigned targets grew farther and farther away. Most of these bombers were F-models, distinguishable by their large, clear nose cones. These clear noses quickly proved to be a weakness, with German fighter pilots learning to attack head-on, spraying machine-gun and cannon shells into the cockpits of American airplanes. Various solutions to this problem were tried throughout 1943, with ground crews experimenting with cutting holes in the plexiglass and finding different ways to mount forward-facing machine guns. While these ad hoc designs solved this issue – ultimately culminating in an entirely new design, the G model – the lack of long-range Allied escort fighters until 1944 meant that 1943 saw some of the heaviest aerial fighting of the entire war.

Of the three major campaigns waged by the US Strategic Air Forces in Europe – submarine pens, aircraft factories, and oil refineries – only two of today’s surviving B-17s took part in these operations:

Memphis Belle (41-24485), a B-17F assigned to the 91st Bombardment Group on 26 October 1942. She was the first bomber in the 8AF to complete a combat tour-of-duty of 25 missions and return home, flying her final mission on 17 May 1943 – mere days before the submarine pen campaign was brought to an end. Memphis Belle was placed on display at the National Museum of the US Air Force in Dayton, Ohio 75 years later to the day.

Shoo Shoo Baby (42-32076), a B-17G assigned to the 91st Bombardment Group on 23 March 1944. Shoo Shoo Baby flew 24 combat missions until 29 May 1944 when, during a strike against Poznań, the bomber made a crash-landing in Sweden after losing three of its engines. Tracked down and identified by historian Steve Birdsall, the bomber was on display at the National Museum of the US Air Force in Dayton, Ohio from 1988 to 2018. She is the only survivor of the 8AF’s oil campaign of 1944 with us today. Shoo Shoo Baby is slated to be relocated to the National Air & Space Museum’s Steven F. Udvar-Hazy Center in the near future.

With your help, the rebuilding of Lucky Thirteen will preserve for future generations an example from the bloody counter-air/aircraft factory campaign of 1943.

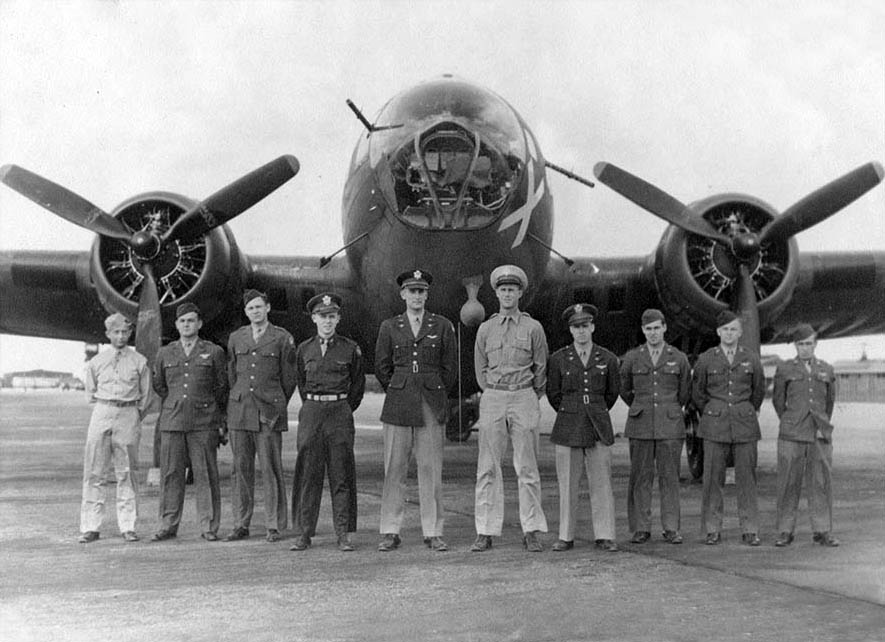

The crew of Lucky Thirteen pose with a training aircraft before leaving the United States.

(Left to Right):

SSGT Harry Saperstein (Ball Turret)

TSGT Oscar K. Hamblin (Top Turret/Engineer)

SSGT James P. Morley (Waist Gunner)

2LT Richard J. Peirce (Navigator)

2LT Warren B. Holland (Co-Pilot)

2LT Jacques E. Riddel (Pilot)

2LT Harry A. Hawes (Bombardier)

TSGT Charles L. Kirby, Jr. (Radio Operator)

SSGT Edward F. Ruch (Waist Gunner)

SSGT William H. Ross (Tail Gunner)

(Not Shown) SSGT Lawrence J. Coon (Crew Chief)

Riddel was killed on 28 July 1943, flying as co-pilot on Sky Queen (42-30032).

He was replaced by 1LT Russel R. Faulkiner.

Boeing B-17F Flying Fortress number 42-3455 was received by the US Army Air Forces on 24 June 1943 and delivered to the Army Modification Center in Cheyenne, Wyoming the very next day. Ordered in 1942 and built by the Douglas Aircraft Company in Long Beach, California, Lucky Thirteen was built as construction no. 8391 under Douglas production block-65, meaning that she was the 491st B-17 assembled under Boeing-contract at Douglas. She arrived for active-duty at Dow Army Airfield in Bangor, Maine on 28 July 1943, crossing the Atlantic and being assigned to the 384th Bombardment Group at RAF Grafton Underwood on 11 August. It was here that Lucky Thirteen received the code letters “BK,” designating her a member of the 546th Bombardment Squadron, and the call letter “M.” Though we do not know for sure, the name Lucky Thirteen may originate with her call letter, as “M” is the thirteenth letter of the alphabet.

Lucky Thirteen‘s combat career reads thusly:

Callsign “Mike-455”

Boeing B-17F-65-DL Flying Fortress

41-3455

546BS/384BG

41st Bombardment Wing, 1st Air Division, VIII Bomber Command, US 8th Air Force

RAF Grafton Underwood (Station 106), Kettering, England

15 August 1943

Mission #1

Aèrodrome de Poix-en-Picardie and Aérodrome d’Amiens-Glisy

Poix-en-Picarde and Glisy, France

16 August 1943

Mission #2

Aéroport de Paris-Le Bourget

Paris, France

17 August 1943

Mission #3

Schweinfurter Präzisions Kugellagerwerke

Schweinfurt, Germany

27 August 1943

Mission #4

Bombsight-AFCE failure; bombs not dropped

V-1 Cruise Missile Launch Site

Watten, France

31 August 1943

Mission #5

Target abandoned due to cloud-cover

Aérodrome de Romilly-sur-Seine

Romilly-sur-Seine, France

3 September 1943

Mission #6

Aérodrome de Romilly-sur-Seine

Target obscured by cloud cover; secondary target bombed instead

Aèrodrome de Saint-André-de-l’Eure

Saint-André-de-l’Eure, France

6 September 1943

Missing Air Crew Report No. 775

Mission #7

Flak damage in right wing resulted in fuel leak, forcing bomber to drop from formation

Shot down by FW-190 over Beauvais, France

Industrial District

Stuttgart, Germany

Click here for details on the escape and evasion of Lucky Thirteen‘s crew after her final mission.

Lucky Thirteen was struck from the Army registry on 11 November 1943.

Lucky Thirteen will be a unique aircraft upon completion.

Some statistics to her into context:

12,731 B-17s were built from 1936 to 1945, with 6,981 built by Boeing in Seattle, Washington, 3,000 by Douglas in Long Beach, California, and 2,750 by Lockheed-Vega in Stockton, California. 49 of these aircraft still survive today.

Of these 49 survivors, two are prewar “shark tails” (one of which is a replica build project), five are E-models, four are F-models, and an overwhelming 38 are G-models. The reason for this is simple – the vast majority of today’s B-17 survivors are those built too-late to see combat. This is also the reason that, of the surviving 49, only ten still wear their original colors and a paltry five ever saw combat.

The counter-air/aircraft factory campaign of the summer and autumn of 1943 was the bloodiest period in the history of military aviation. As such, the rebuilding of Lucky Thirteen will create a lasting memorial to those who fought and died in the skies over occupied-Europe.