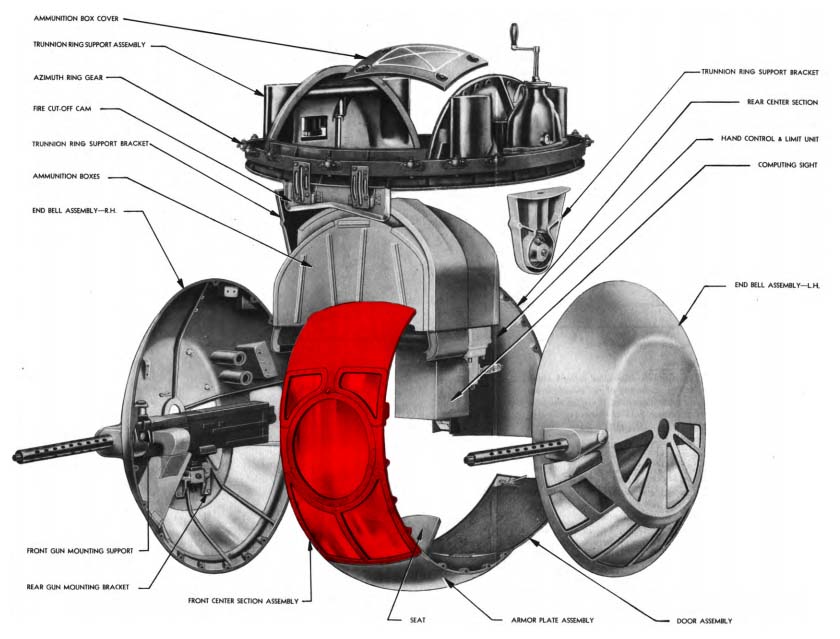

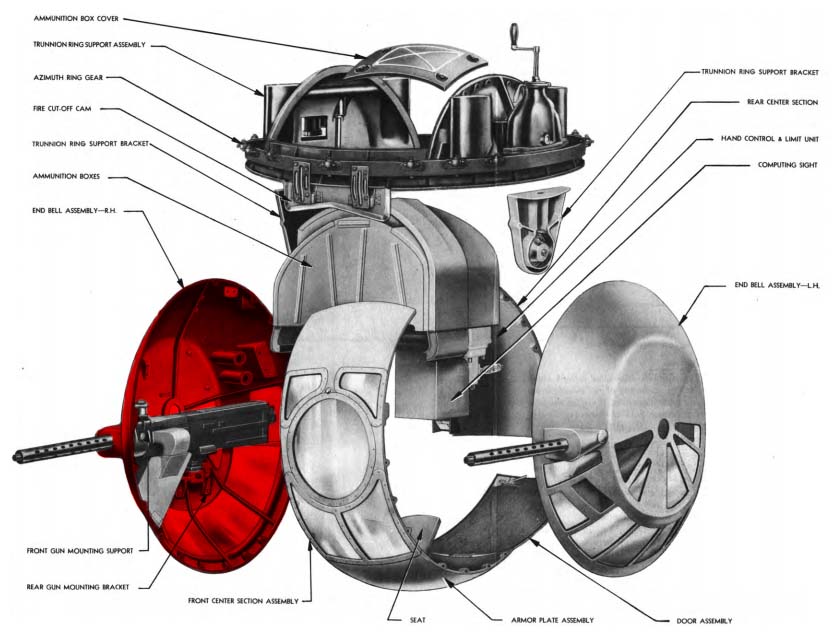

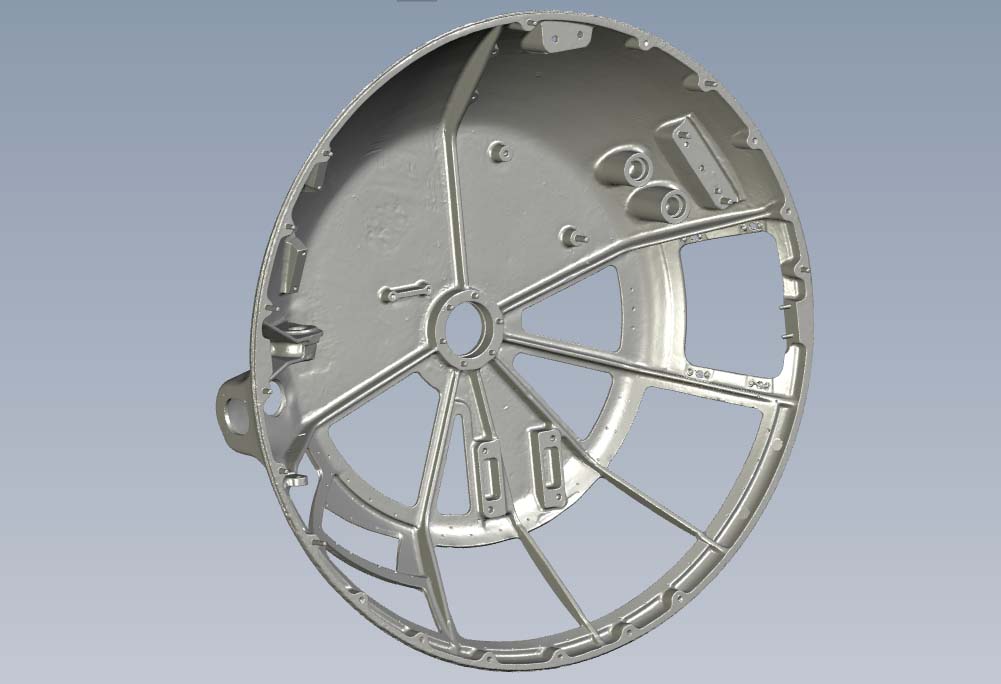

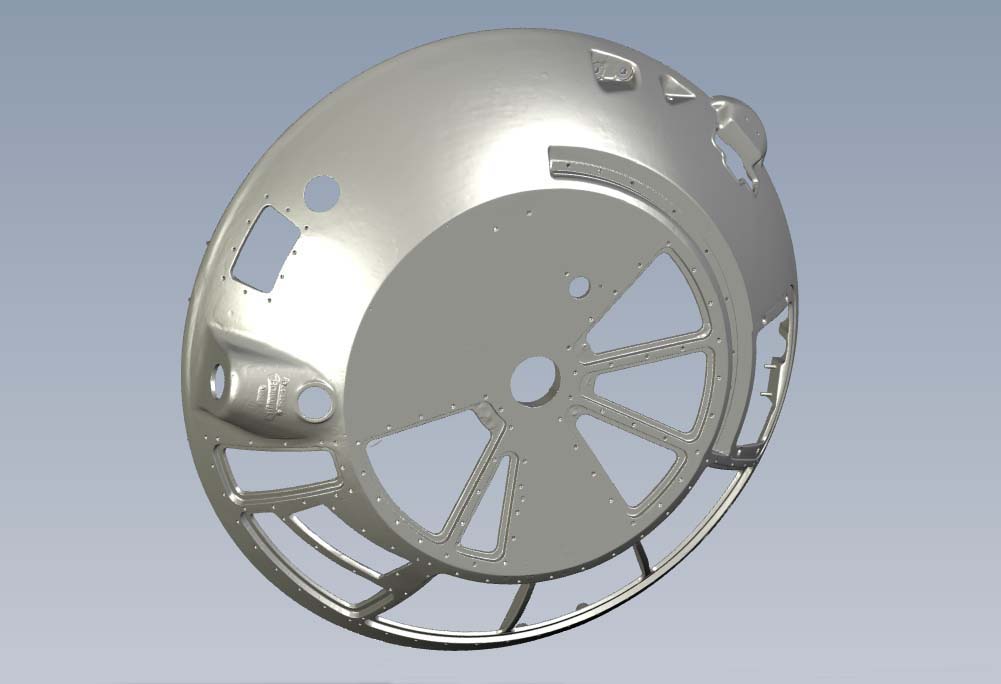

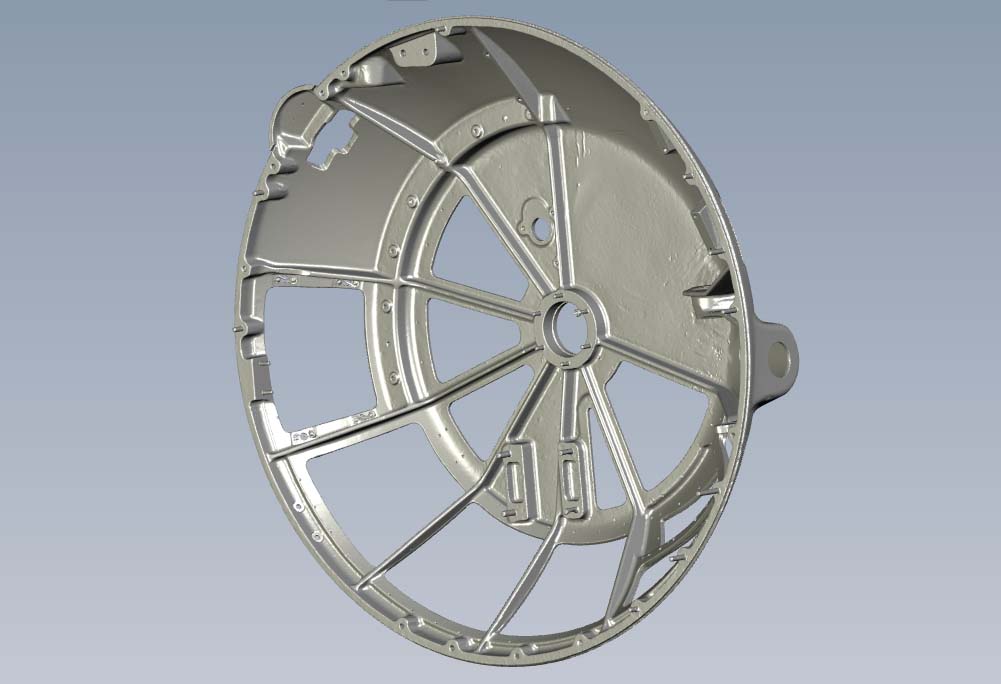

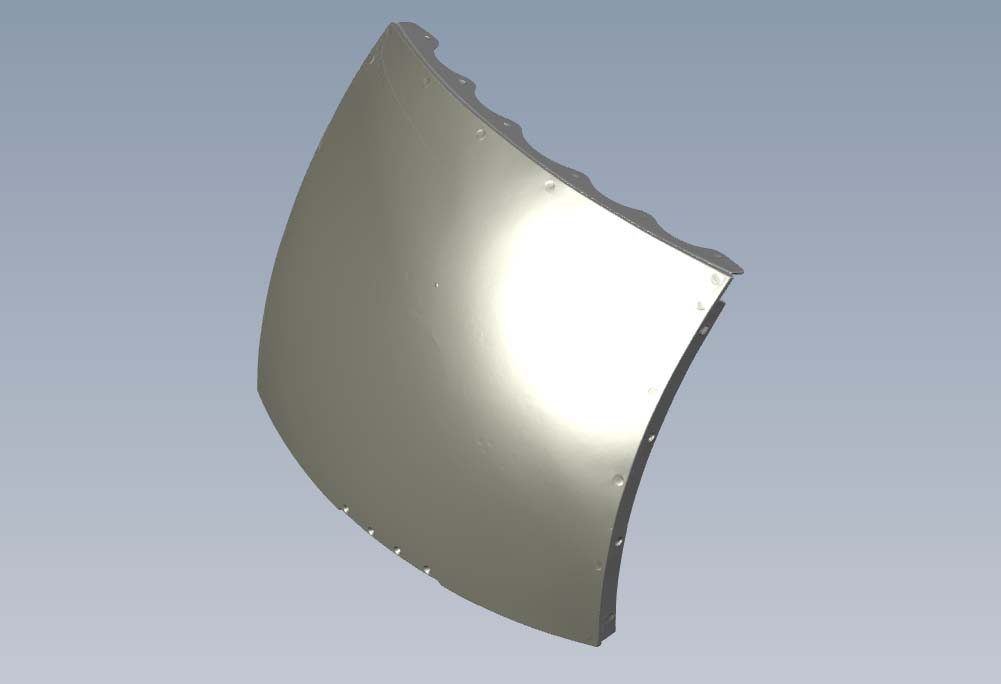

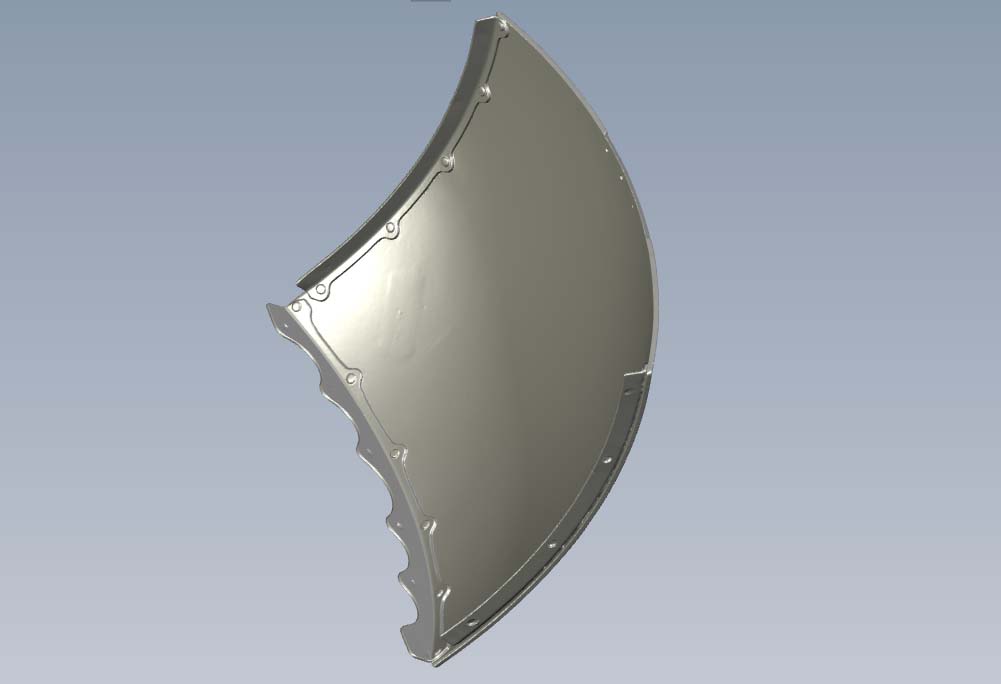

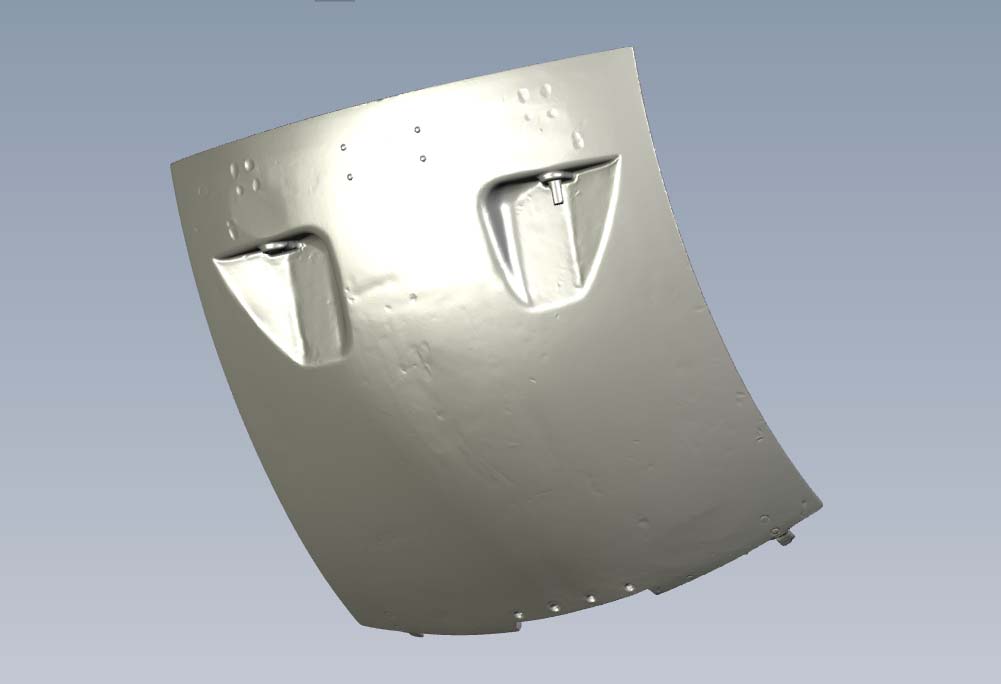

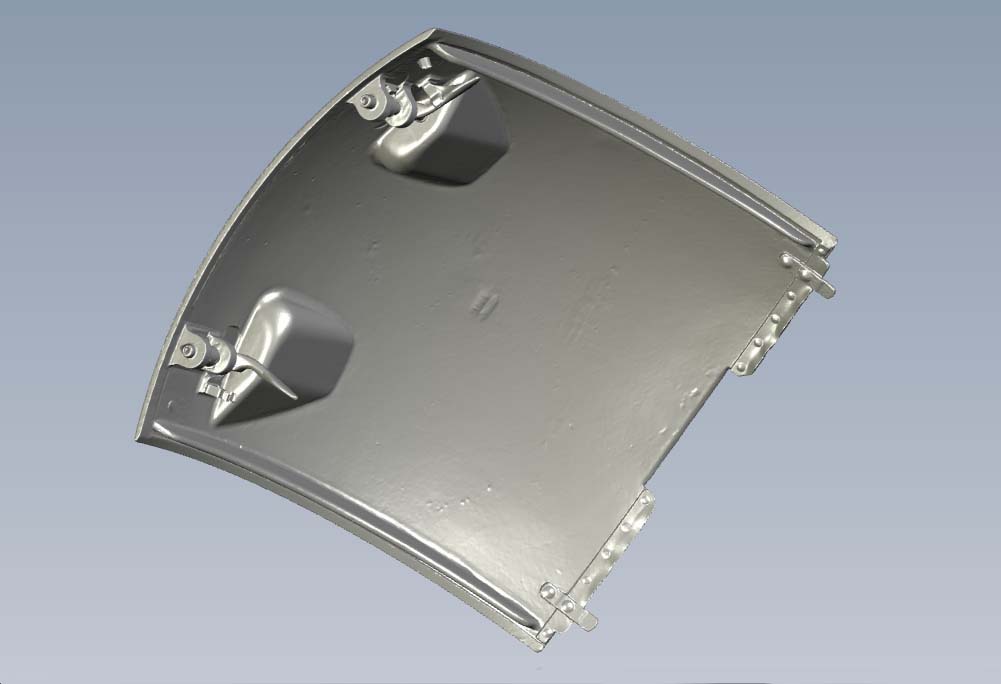

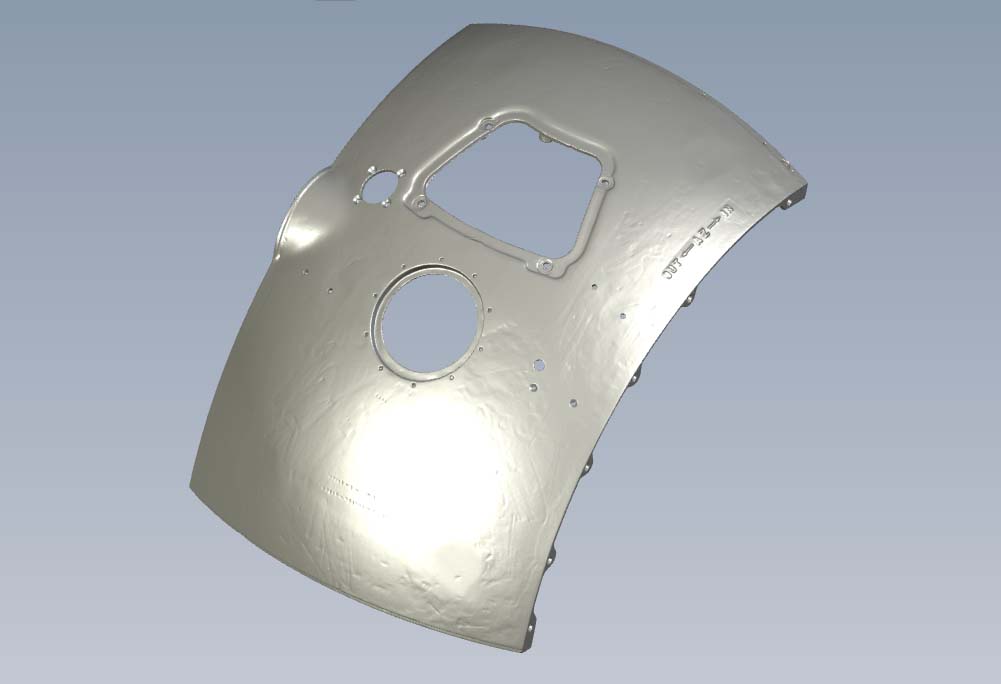

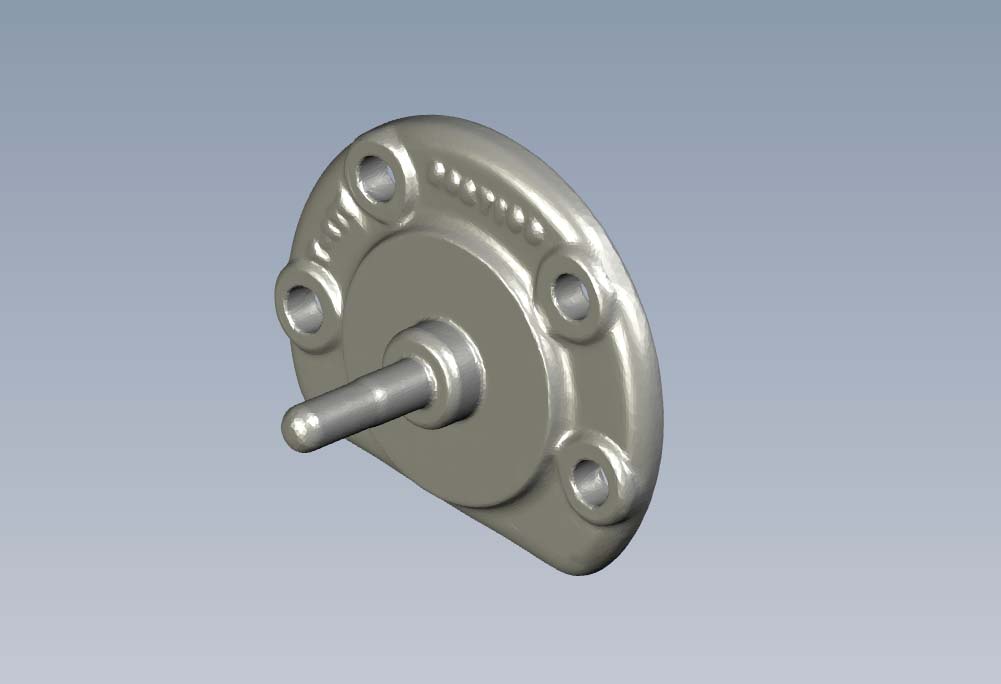

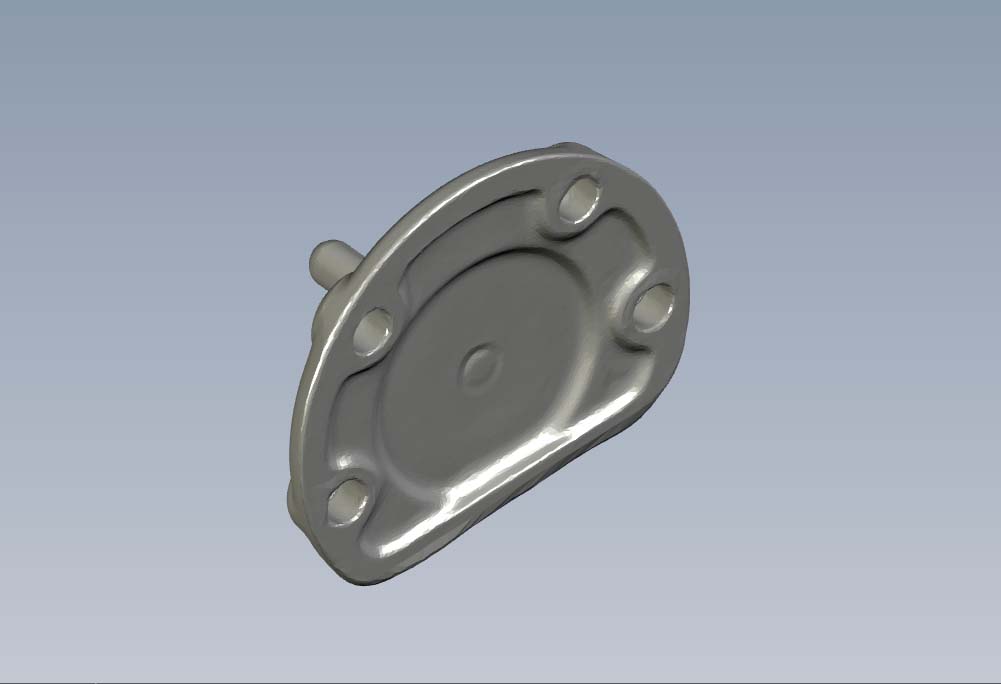

The Planes of Fame Museum’s Type A-2 ball turret disassembled for 3D scanning.

There is probably no piece on the Boeing B-17 more iconic than the Sperry ball turret. And when it comes to rebuilding the ball turret assembly for Lucky Thirteen, this brings a whole host of problems.

To begin, it is worth noting that the number of surviving B-17 turrets today is far smaller than one might think. While the B-17 found a multitude of odd jobs after the war, none of them required the old bombers carry around these bulky, heavy pieces of equipment. So when the postwar preservation movement began to gather steam, finding any turrets at all was something of a miracle. This is the reason that so many B-17 survivors carry false top turrets (just the dome) and Type A-13A ball turrets – a late-war design primarily intended for the Consolidated B-32. Since the B-32 saw little service, the result was a postwar surplus of A-13As, many of which were recovered for the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora!

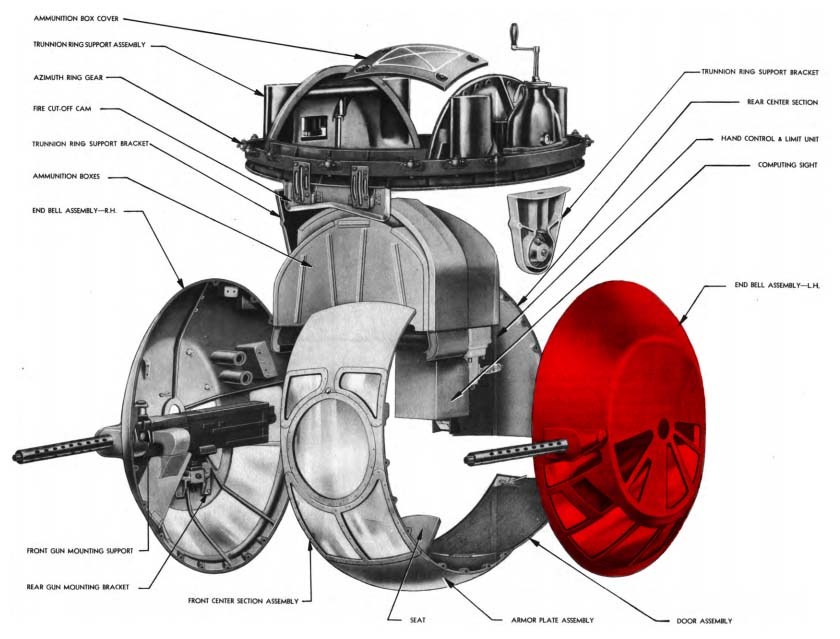

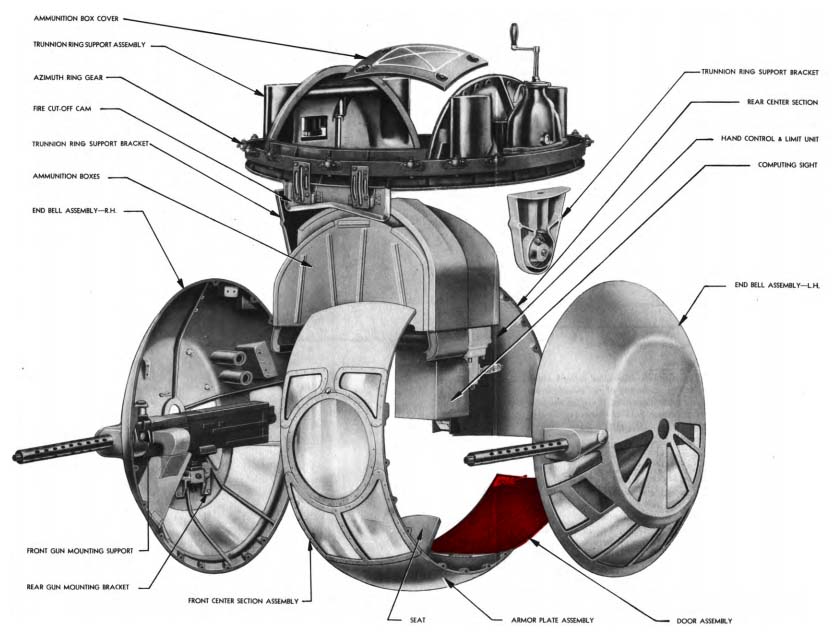

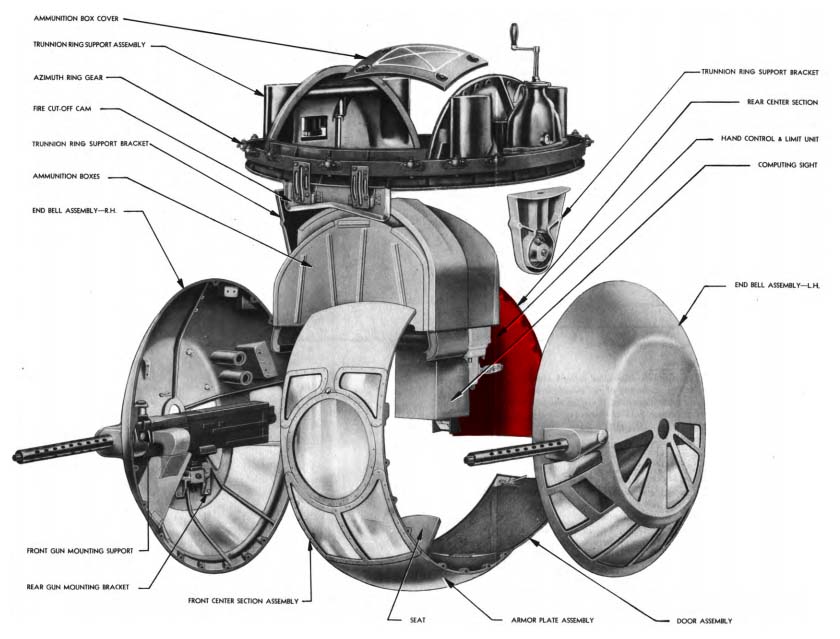

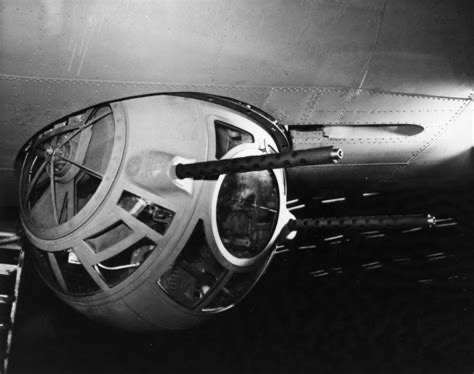

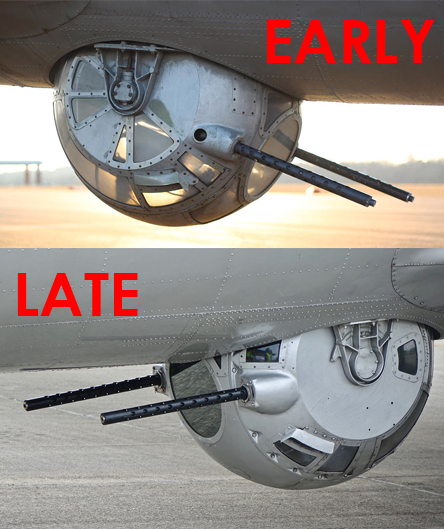

The above turret is a Type A-2A, the bottom a Type A-13A. No B-17 ever served with the turret shown below.

Hangar Thirteen is entirely dependent on small donations and popular support to make what progress we can. Because of this, the opportunity for us to acquire complete examples of early top and ball turrets has always been slim. So the alternative is to rebuild the turrets from scratch. You see, it is far easier to obtain turret ‘guts’ – i.e., gears, motors, controls, etc. – than it is the turret bodies themselves. So if we can cast these bodies anew, we can fit them out with original equipment, in the process restoring and rebuilding from the bottom up.

Unfortunately, none of the original companies involved with B-17 turret production, be it designer Sperry Gyroscope of New York, or manufacturers Steel Products & Engineering Co. (SPECO) of Ohio, Emerson Electric of Missouri, and Briggs Manufacturing of Michigan, still retain their original blueprints. And research into the Smithsonian’s archives proved less than fruitful. Hence our recent effort toward 3D scanning.

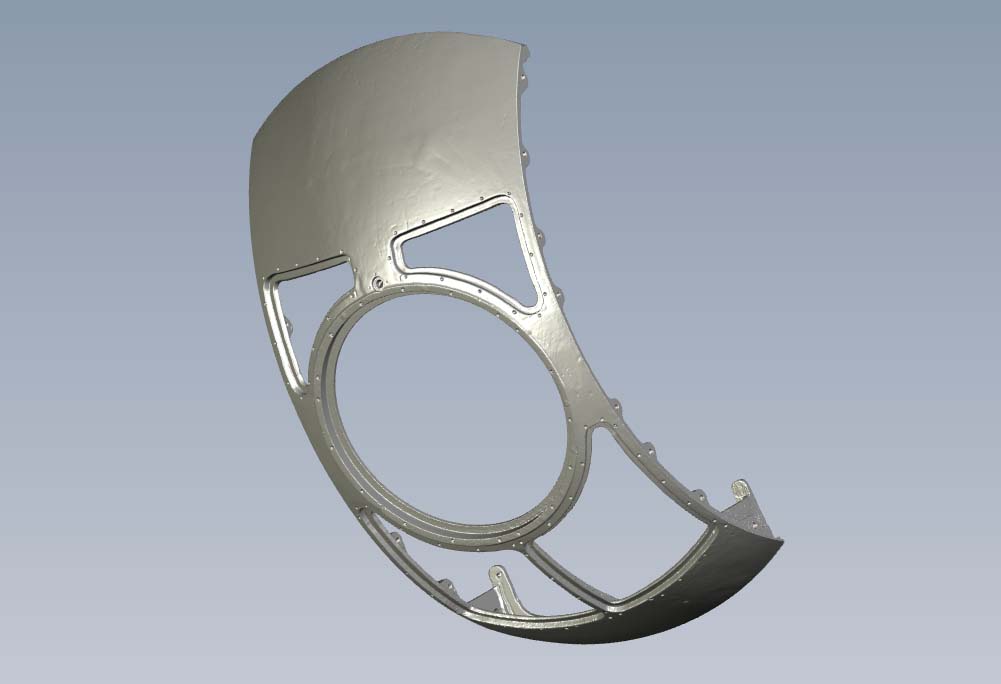

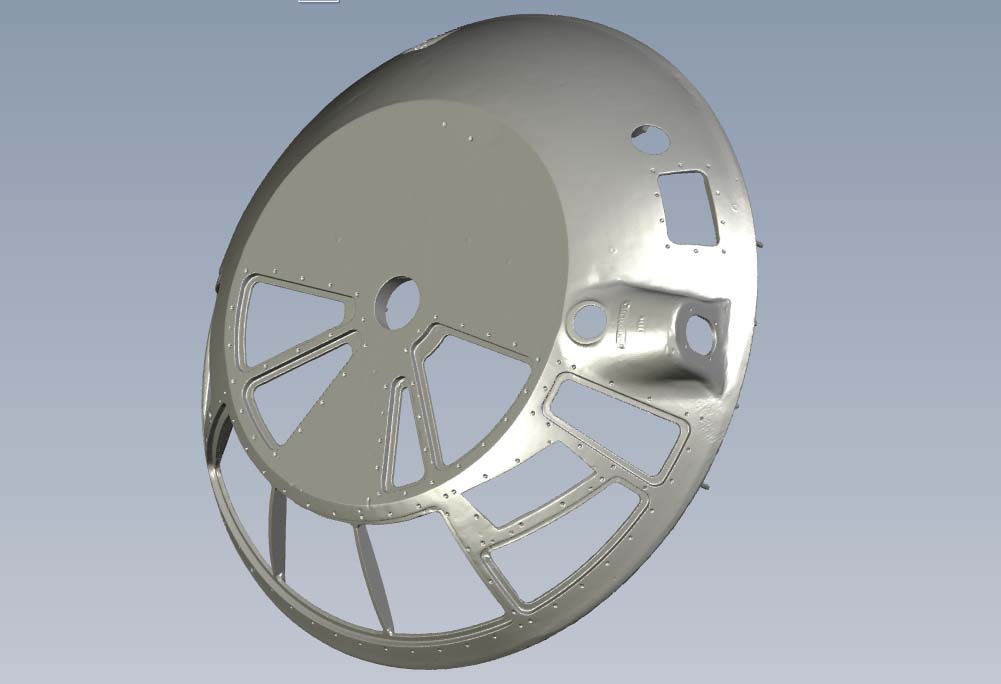

As mentioned before in our post on the top turret housing, 3D scans allow us to reverse engineer the parts to create solid computer models, which can then be given to a foundry to cast the parts anew. Unlike casting from an original, computer models not only allow us to compute for the natural shrinkage which occurs in the casting process, but it also means that we are not bound to a single foundry or a specific timetable. A local collector has been kind enough to allow us to 3D scan his early top turret, scanning individual components as funds allow. And an early ball turret hanger assembly has been offered to us for the right price, should we manage to raise the funds. But for a long time, we have not been able to locate an early ball turret – a Type A-2 – whose owner was willing to disassemble the ball for scanning. Until now.

It turns out that our friends at the Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California have an early ball turret in their collection, and they were willing to disassemble said turret for 3D scanning. Hiring the services of RapidScan3D, who are located nearby, we can now reverse engineer this amazing piece of history. The only pieces that we have not been able to locate, either for acquisition or scanning, are the ammunition hatch cover and side caps unique to early ball turrets.

A very special thanks to the guys at Planes of Fame for being such amazing friends and the team at RapidScan3D for their incredible work in keeping history alive.