This article was originally published in the Fall 2004 issue of Flight Journal and is reproduced here with permission.

This account of Lucky Thirteen‘s sortie over Schweinfurt was taken from the memory of SSGT John F. Schimenek, who was 87 at the time of the interview. As such, the article has numerous errors of memory – please bear this in mind.

“Lucky 13 – Surviving The First Schweinfurt Raid”

as told to and written by Jan Tegler

17,000 feet over the French Coast,

August 17, 1943

“They knew we were coming, and picked us up shortly after we passed the French coast. [Fw] 190s and [Me] 109s chased us all the way in. The first attacks came 80 to 90 miles into France.”

The biggest WWII daylight-bombing raid to date was off to a bad start. Foul weather in England delayed the launch of the second massive wave of 8th Air Force bomber divisions. The lag gave the Luftwaffe time, which proved to be very costly to the First Air Division.

-81-

The crew of Battlewagon/Lucky 13 after they flew their 25th and final sortie: a mission to Berlin. Standing from left to right: McClanahan; Lt. Philip Algar, pilot; Col. Harris (384th BG CO); Lt. Frank Celentano, navigator and a replacement pilot, name unknown. Kneeling: unknown crewman; S/Sgt. McKay; S/Sgt. John Schimenek, left waist gunner; S/Sgt. Mike Majewski, tail gunner and T/Sgt. Lavialette, engineer. (Photo courtesy of John Schimenek via author.)

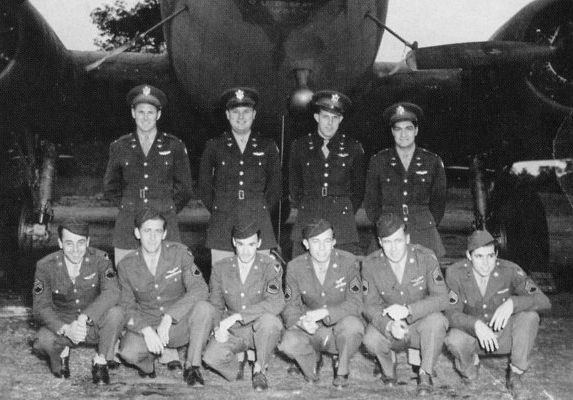

John Schimenek and Battlewagon’s crew and men from other crews post under the B-17’s nose after their 11th mission to Poix, and an airfield at Amiens, France. Battlewagon took a significant hit from triple-A in its horizontal stabilizer on this mission but returned the crew safely to Grafton-Underwood. S/Sgt John Schimenek kneels at the far left of the bottom row. (Photo courtesy of John Schimenek via author.)

The dual mission to Regensburg and Schweinfurt was the first deep-penetration strike into Germany – a historic turning point in the War. The strike was a maximum effort and was composed of 376 B-17s in two air divisions. The Third Air Division, commanded by Col. Curtis LeMay, was to bomb the Messerschmitt factory in Regensburg then proceed to advanced air bases in North Africa, thus making it the War’s first “shuttle” mission. The First Air Division was to target the ball-bearing factories in Schweinfurt and return on a reciprocal route to England.

Twelve bomb groups and three composite groups formed the First Air Division. One Group was the 384th BG, based at Grafton-Underwood. At 26, S/Sgt John F. Schimenek was an “old man” in comparison to other Fortress fliers. A waist gunner with the 545th BS, he and his crew (three-fifths through their 25-mission tour) arose long before daylight on August 17, 1943, for the morning briefing. At the briefing, they learned just how big the mission would be and which airplane they would fly. The crew’s regular Fortress, Battlewagon, had been riddled so severely on a mission German-occupied airfields in France two days earlier that it was out of action. Lucky 13, a [B-17F], would be the crew’s mount for the day.

The plan was for the Third Air Division to launch first. The First Air Division would follow a short time later and penetrate enemy territory 10 minutes after the Third. A dense, swirling fog over East Anglia delayed the Third Division’s launch by one and a half hours; most of its groups lifted off at about 7 a.m. Four and a half hours later, the First Air Division’s 230 B-17s started their takeoffs. To a man, the crews were incredulous that the mission hadn’t been scrubbed. The impact of the delay was frighteningly clear. “The high command didn’t have the sense to call it off. The Regensburg mission was supposed to take off first to draw up the Luftwaffe fighters. Then we were supposed to go into Schweinfurt with little fighter opposition. They were supposed to be on the ground refueling and rearming, waiting for the First Group to turn around after the bomb run. Instead, they raised hell with us all the way!”

The wait had been hard on the crews; many had not eaten since 2 o’clock that morning. Frustration and anxiety gave way to adrenaline as they took off. “We had flown 15 missions by then, and I had long since calculated that I probably wouldn’t live through the rest. It was harder and harder to get into the airplane with those kinds of odds. We rarely had fighter support, and we knew we couldn’t do it all alone. But we just kept going.

“Everything that could fly went. It was a maximum effort, so we knew it was big. We took off and did 360s around our individual airfields until everyone go up to altitude, and then we joined up. We were the lead ship in the 384BG; off to one side in the First Division and as far as we could see behind us were aircraft. It was hard to believe. RAF Spitfires went with us to the limit of their

-82-

For their 19th mission to Wilhelmshaven, Germany, Battlewagon’s crew flew as the lead ship and carried a lot of officers aboard. Standing: Capt. Stallings; McClanahan; Lt. Frank Celentano and Lt. Philip Algar. Kneeling: S/Sgt McKay; S/Sgt. John Schimenek; S/Sgt. Mike Majewski; S/Sgt. McKay and T/Sgt. Lavialette. (Photo courtesy of John Schimenek via author.)

range – not very far, just over the Channel. P-47s were supposed to pick us up there, but they never showed.

“As soon as we made landfall over the French coast, the 88mm ack-ack guns opened up on us. Their flak was accurate. They had had lots of practice. Shortly after, we started to lose aircraft. We could look behind us because of the clarity of the day and see a funeral-like pyre of smoke where a B-17 had gone done. You see it for an awfully long way. We were constantly on the lookout for fighters. I was flight control with regard to firing, and I told the other gunners, ‘When you see an enemy airplane, wait until it’s in range to shoot. Don’t follow anything you hit down with the gun. Always keep your eyes up because if you don’t, the next guy will shoot your tail off. I think that advice helped us get back – that and our luck. We had a lot of it.

The first attacks came 80 to 90 miles into France. Enemy fighters came out of the sun at our 4 o’clock position. They’d come from our right to our left and back right again, lining up in single file, one behind the other. The guys in the low groups really caught hell. It was very hard to hit fighters when they’d split-S’d away from us at 500 mph. Plus, all of the guns in the formation couldn’t be brought to bear on them or we would have hit our own people. I’m pretty sure there were mistakes that led to friendly-fire incidents. We were in close formation, and a guy who wasn’t paying attention and hung on his trigger long enough could easily have hit another B-17. Within 900 yards, we fired at them. I think I burned all the grooves out of my barrels. In the middle of the attack, before we hit our IP, we noticed that they started to fire what had to be rockets. The 190s had those mounted, two on each wing. When I saw the white exhaust trails spew from them, I would call for the our pilot, 1st Lt. Philip Algar, to pull up about 10 feet, and the rockets would pass underneath us. Our ball-turret gunner, Sgt. McKay, said “Shimeneck, you old coot! Don’t make a mistake, or we’ll all go to hell in a basket!”

I was firing away, when suddenly, I was pivoted around. It felt as if I had been hit by a rug-beater when a 20mm slug came through and hit the left waist gunner, Corwin Miller, and me. I wasn’t hit badly, and when the round exploded, it clobbered my left arm, which was saved by my heavy leather jacket, my winged underwear, and all the clothes I had on. It drew blood in four places but not badly. It scared the hell out of me, though, and I grabbed my arm thinking I had lost it. Miller yelled, ‘Shim, I’m hit!’ He slumped over, and I grabbed him and laid him down. He was hit in the back; one lung was pierced, and he was bleeding internally. He immediately started to cough up blood into his mask; I knew I had to get it out. It was about 40 degrees below zero up there, and I was afraid he’d die from lack of oxygen if the blood froze in his mask. There was a pith ball in the oxygen mask that looked like a bubble. If the bubble rose routinely, he was breathing. If it stayed still, he wasn’t. When it stopped, I’d grab him and wipe the blood out of the mask, and he’d cough up more. He lay there on the deck for five and a half hours.

“We were concerned about keeping him from freezing, too. It just so happened that on a previous mission, we were shot up pretty badly and had a fire in the no. 3 engine, and we had to land at RAF Coltishall on the White Cliffs of Dover. After we were down, tail gunner Mike Majewski and I walked by one of the [Brits] storage sheds and I saw a big pile of English blankets stacked in one. I said, ‘Mike, grab four blankets or more.’ He said, ‘What the hell? It’s summertime, you don’t need any blankets.’ Grab four blankets; do it!’ I said. I just thought that those blankets might come in handy if we were hit. Dr. Stroud, the flight surgeon who worked on Miller, later asked how in the hell we had kept him from freezing. Those four blankets kept him warm. We wrapped him in them like a papoose, and I turned his rheostat (in his electric-heated flying suit) up to 25 degrees C.

“As we passed over the IP and headed for Schweinfurt, things were pretty hot. Never a dull moment. Forts were going down all around us. Majewski and I managed a couple damaging hits

-84-

The Battlewagon’s crew dressed in Class A uniforms. Standing: 1st Lt. Clifton McClanahan; Lt. Philip Algar, pilot; Lt. Wolf, copilot and Lt. Frank Celentano, navigator. Kneeling: S/Sgt. John Schimenek, left waist gunner; S/Sgt. Mike Majewski, tail gunner; T/Sgt. Lavialette; S/Sgt. McKay; T/Sgt. Frank Gerow, radio operator and S/Sgt. McKay. (Photo courtesy of John Schimenek via author.)

B-17s from the 384th BG etch contrails on a high-altitude run over Europe. The crews hated the contrails because they were dead giveaways of their positions. (Photo courtesy of John Schimenek via author.)

on Me 109s and Focke-Wulfs, but there was no time to follow them down. I went back and forth between my position and Miller’s, firing both guns. I’d run from one gun to the other on instructions from the tail gunner. I also had to remove my gloves to clear Miller’s mask. We had the old bladder-style masks; they were the greatest. A guy I knew in a ball turret had heaved in his and it froze and he suffocated.

I tried to get the radio operator, S/Sgt. Frank Gerow, to come back and help Miller when he went down. We wanted to give him morphine. Gerow wouldn’t do it. So I said, ‘Go back to the radio room. I’ll do it.’ Miller later told me, ‘When you shot me the morphine, it felt as though you put a road spike up my elbow!’ I said, ‘Well, maybe I was a little nervous too!’ That 20mm had exploded by the radio room, right over Gerow’s shoulder. When the radio room was hit, a part of the oxygen system failed, and we lost oxygen on one side of the airplane.

The 20mm slug that came through the tail really frightened us. It hit our big radio compass and deflected and sent fire up the catwalk right up by my feet. Scared the hell out of me! I was just about to go out the waist window, when I looked down over my shoulder and saw the fire die down, and I came back in; I didn’t want to be blown out. I had seen it happen too many times. There was a hole where the 20mm had come in, but the old boat kept plugging right along.

We continued on in and dropped our bombs on Schweinfurt. After our turn away from the target, we all took a half-ass vote and agreed to try and save Miller. Lt. Algar got permission for us to leave the squadron when we were about even with Paris and took us down to 12,000 feet so we could save our remaining oxygen for Miller. At 12,000, we could breathe OK if we didn’t move around too much. The German fighters had left us when we made the bomb run. They didn’t concern us to much now because they were at their bases to refuel and re-arm. The navigator, 1st Lt. Frank Celentano, plotted the shortest route back to England and got us on course. We took some 88mm flak, but it wasn’t too bad.

We got back to Grafton-Underwood a good 20 minutes before the rest and shot a flare to alert them of wounded aboard. They were ready for us when we touched down. Dr. Stroud came aboard to get to Miller, and I told him, ‘His chest is full of blood.’ Stroud pulled out a big needle and sucked out all the blood and later gave it back to him in a transfusion. They took Miller to the hospital and told me to go, too. But I said, ‘No, forget about me. I don’t want word to get home that I’ve been hit.’ I didn’t want my elderly mother to worry. Of course, then it came out in the local paper about three days later, and I caught hell for not telling her.”

One hundred eighty-seven Fortresses from the First Division dropped their incendiary bombs on Schweinfurt. Sixty B-17s were lost, five from the 384th. The War ended that day for Corwin Miller. He recovered fully in the 160 Station Hospital in England and was shipped home. S/Sgt. John Schimenek and the rest of Lucky 13‘s crew completed their tour. According to Schimenek, the fragments of the shrapnel that nearly took Miller’s life are still inside his arm, never having been removed.

-85-

Special thanks to Flight Journal magazine for allowing us to reproduce this article.

Special thanks to Flight Journal magazine for allowing us to reproduce this article.