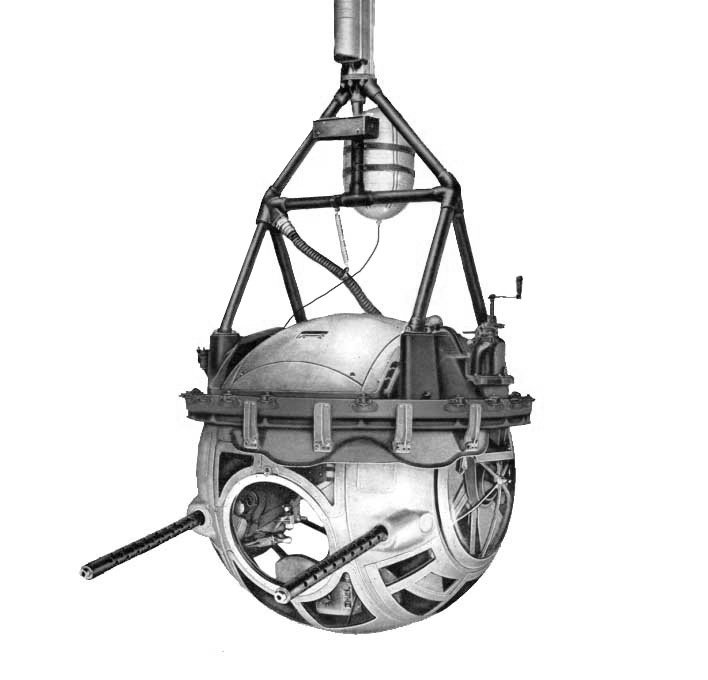

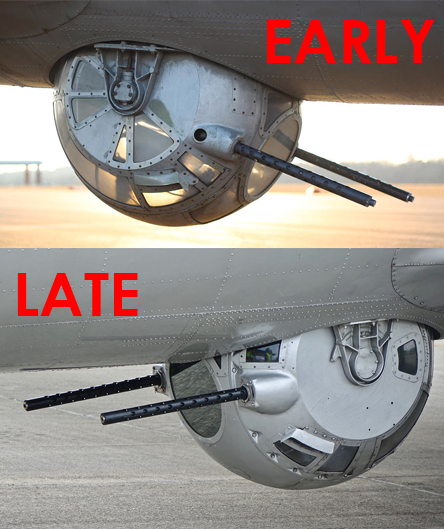

An illustration showing an A-2 Ball Turret like the one that was installed aboard Lucky Thirteen.

LUCKY THIRTEEN‘S NEEDS

To pick up where I left off on the last turret article:

The Sperry ball turret’s recognizability is its biggest enemy.

As mentioned before, most of today’s surviving warbirds which still have turrets only managed to do so by creating Frankenstein amalgamations. But unlike the A-1 Upper Turret, not only does the A-2 Ball Turret not take up valuable cockpit space, it is also a guaranteed crowd pleaser. As such, any attempt to restore/rebuild a ball turret must contend with competition from collectors, but also from other projects who recognize its popularity. For example, this is the reason that no attempt has ever been made to preserve the history of radar-equipped Pathfinder aircraft – it would require losing the ball turret.

Radar-equipped Pathfinders of the 452BG. Two of today’s surviving B-17s were originally Pathfinders – one in combat and one as a trainer.

This has resulted in a unique situation for our work on Lucky Thirteen. On one hand, ball turret parts are somewhat easier to locate than upper turret parts. On the other hand, those who have ball turret components are loathe to part with them. We know of multiple ball turret shells (i.e., the ball itself) that are not currently mounted to an aircraft, but none of the owners of said shells will entertain trading/selling/donating.

So, we have worked under the assumption that no original will ever come our way. In 2022 we were able to 3D scan the A-2 currently in storage at the Planes of Fame Museum in Chino, California. This arrangement worked beautifully. Now we are in the process of reverse engineering these scans. Once that is complete, we will have the computer files necessary to machine molds and eventually cast the ball anew. In the unlikely event that we are offered an original ball turret, at least we will have the files saved for posterity (as the original blueprints are long gone).

An A-2 ball turret hanger and trunnion assembly, like the one seen here, has been offered to us at 25,000 if we can raise the funds.

In general, we have tried to focus donations toward the upper turret, simply because its parts are harder to find. I have no doubt that, with the appropriate funds, we could gather all the ball turret gearings necessary for a live bench test in a matter of months. Still, we have made some progress gathering interior components, acquiring such pieces as the double power unit, gunsight mount, Edgewater adapters, F-1 oxygen tank, gun recharge pullies (which have been restored), bulletproof glass, azimuth power gear, and the fuse box and ammunition magazine. It is the exterior components which are more troublesome. So far, we have been offered a trunnion assembly, complete with an early hanger, at the price of 25,000 USD. We have not come close to that mark so far, so it is our genuine hope that no one swoops in and takes it before us.

Assuming an original does not come our way, if we were able to purchase said hanger and trunnion, and cast the ball anew, the only major exterior components left would be the ball’s interrupter and *electrical brush assembly.

*An electrical brush assembly has been located and acquired since publishing this article.

HISTORY

It is perhaps best to begin any discussion on the ball turret by acknowledging that it is one of the most misunderstood pieces of equipment in military history. This should not be surprising. It was an unworldly design which still fascinates all who see it – and that is the problem, as too often fantasy supplements, and overshadows, banal reality.

As noted before, US observation reports in the opening years of the Second World War recommended implementing a crash program to outfit heavy bombers with powered turrets covering all four approaches: above, below, ahead, and behind. Since interwar US bomber design was focused on aircraft performance, the Air Corps’ limited research into aerial gunnery had revolved around the concept of “fire control.” The idea was to not saddle the bomber with any defenses which might severely affect the its speed and altitude. While fire control did not find success until the waning years of the Second World War, the concepts behind it were sufficiently studied as to allow the US to favor electric turrets over the hydraulic ones used by Great Britain.

A “bathtub” belly gun aboard a Boeing B-17C.

The need for ventral defense on bomber aircraft had been recognized as early as the Great War but the issue was never easily solved. Gothaer Waggonfabrik was the first, developing a recessed belly fuselage for gunners on their successful Gotha bombers. This technique was simple and effective and could be found in various forms on Second World War aircraft such as the Heinkel He-111, Handley Page Hampden, and early variants of the Boeing B-17. The problem was that these designs were cramped and suffered from restricted fields of fire. “Dustbin” turrets, first introduced with the Handley Page Heyford in 1934, had greater fields-of-fire but caused immense drag and took up valuable fuselage space. Periscope-aimed powered-remotes seemed the obvious solution at first , and early variants of the Avro Lancaster, North American B-25, and B-17E were equipped with such designs (the Frazer Nash FN-64, Bendix A-6/A-10, and Sperry 645705D, respectively). However, belly remotes were clumsy, difficult to aim, and had a frightening tendency to give their gunners vertigo.

A rare photo of the short-lived Sperry belly remote turret. Despite popular misconception, this turret was NOT made by Bendix, though Bendix did design a similar remote for the North American B-25.

Sperry Gyroscope’s ball turret presented a ‘best of a bad situation’ to the issue of ventral defense. The turret assembly took up little space in the bomber and offered excellent defensive coverage with minimal parasitic drag. But it was not without its vices. Like its upper turret sister, the ball turret was heavy and, more importantly, required heavy bracing to be mounted to the airplane. And, famously, while the ball was designed to fit the average American male, it had been designed without foreseeing the future of heavy flight equipment. As a compromise, ball turret gunners were usually chosen on the basis of stature, the idea being that smaller gunners would be more comfortable and could, if small enough, fit their parachutes inside (which few could).

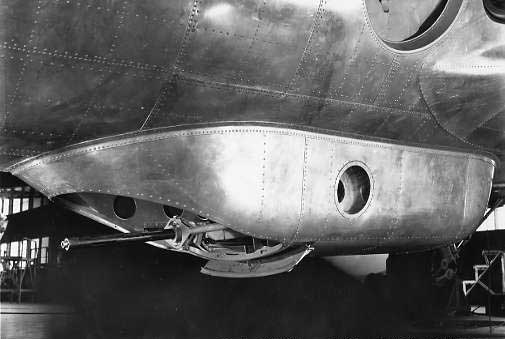

The A-2A Ball Turret aboard Pogue Ma Hone (42-31060, 303BG).

MYTHS

It is perhaps prudent to stop here and cover the oft-repeated story of the ‘crushed ball turret gunner.’

Put simply, there is no evidence that this incident ever occurred.

The story originates from journalist Andy Rooney, who reportedly witnessed such an occurrence while working with Stars & Stripes. It was a popular subject for him. Pres. Reagan told the story once at a press junket, Steven Spielberg adapted it into an episode of his short-lived series “Amazing Stories” (1985-1987), and Rooney verbally recounted it for the History Channel’s “WWII in HD” (2009), complete with voice actors recreating audio transmissions. Unfortunately, this is an extreme example of what a friend once called ‘beating history with a shovel.’ What my friend was referring to was the tendency of people to glorify the past by emphasizing its gorier aspects, under the mistaken assumption that the more nihilistic one’s interpretation is, the more realistic it must be.

This is unfortunate.

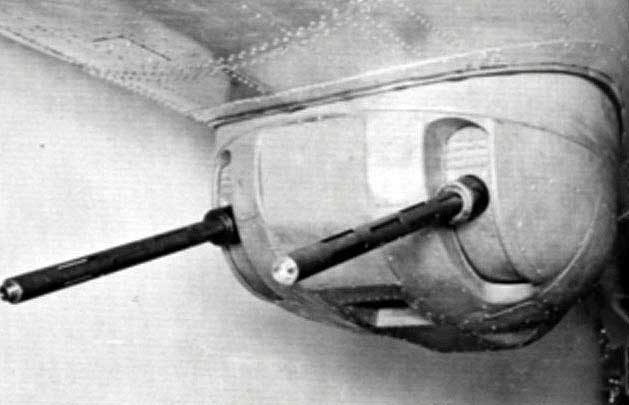

The issue here is that the story does not stand up to scrutiny. While the ball turret had hydraulic transmissions, the turret itself was electrically powered, and even if it had suffered an electrical failure, there were hand cranks inside and out which could transverse the ball to release the gunner inside. This fact, along with other safety measures such as its knockout window and jettisonability, brings the entire narrative into question. Rooney’s retellings of this event rarely correlated with one another and simply repeat a rumor which was common amongst US servicemen during the war. However, it should be noted that US Army records were exceptional and one can guarantee that the turret’s manufacturers would have demanded information on such an event to prevent it from happening again. If such an event had occurred, it would have been a matter of record rather than rumor.

And while the ball turret’s operation can be easily researched online, the story continues to be repeated without question. The photo above, for example, comes from Donald Miller’s Masters of the Air (2006), complete with a caption about a ‘crushed’ gunner due to a ‘damaged hydraulic system.’ The photo comes from Pogue Ma Hone (42-31060, 303BG), which suffered a landing gear failure on the night of 20 January 1944 (almost certainly caused by pilot error). No one was in the turret as, not only was the aircraft on a cross-country flight, but standard procedure required the turret be empty on landing and takeoff. Such accidents tended to damage the balls due to the asphalt rubbing against the metal. Accidents over grass tended to preserve the turret as, after all, the cast aluminum of the ball was stronger than the aluminum sheet above, usually resulting in the ball being pushed up into the fuselage.

THE SPERRY A-2 BALL TURRET

The Sperry Ball Turret was produced in two major series, the A-2 and A-13. The former for Boeing, the latter for Consolidated Aircraft. Originally, these two were almost identical, the only difference being the hanger assembly, as the A-13 required a hydraulic handpump to retract the turret into the the B-24’s fuselage for ground clearance. As with the A-1 Upper Turret, the A-2 was license built, this time to Briggs Manufacturing, a autobody maker in Detroit, Michigan. Attempts to supplement Briggs production with Emerson Electric of St. Louis did not gel as well as they did with the A-1. Briggs resented Emerson encroachment into their defense contracts, as did Vickers, the producer of the Sperry double power unit. While information is scanty, it appears that this rivalry affected production as it is clear that Emerson ball turrets were not as common as those built by Briggs – which is surprising. Resources we have gathered thus far make no mention of Emerson-built ball turrets after 1943.

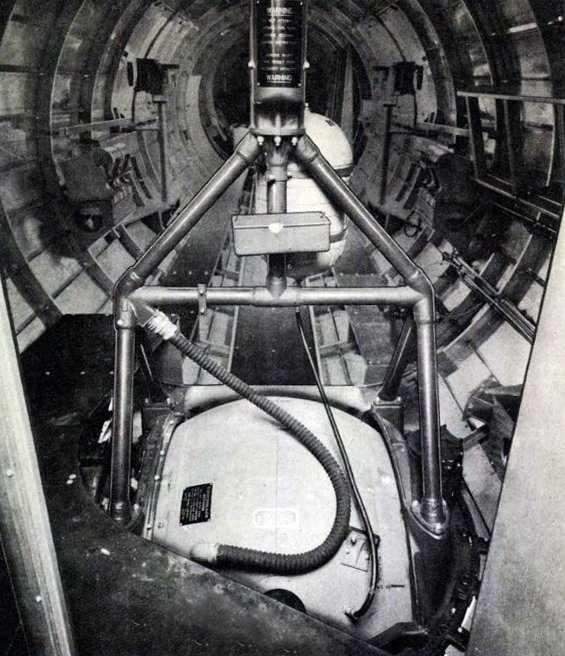

An easy way to differentiate Briggs and Emerson ball turrets: Briggs turrets usually had gray interiors, Emersons had green interiors. The double power unit, built by Vickers, was always painted dark green.

Roughly described, the gunner sat in a fetal position inside the ball. The seat plate and the portion of the ball behind the gunner’s back were both made of armor plating. The turret was controlled by a hand control with cork handles, though plastic handles were eventually introduced to add a ‘dead man’s switch’ (because examples have been found on multiple turret variants, we believe the plastic handle type was a supplementary kit). The gunner’s left foot adjusted for range on the computing gunsight and his right foot activated the push-to-talk button via a toe switch. Rather than an interrupter gear, the ball turret used a fire cut-off cam, which depressed a switch above the center window whenever the turret was aimed at an obstruction. Ammunition was fed to the guns via an internal ammunition magazine, which held just over 1,000 rounds.

Type A-2 Ball Turret

B-17E 42-2505 through B-17G-20-BO

Type A-2A Ball Turret

B-17G-20-BO through B-17G-110-BO

Type A-13 Ball Turret

B-24D-140-CO through B-24J-185-CO

Type A-13A Ball Turret

B-24J-185-CO though B-24M-45-CO

B-32

Again, two major myths should be noted here:

First, there is no evidence that the B-17 ever carried a ball turret with externally fed ammunition cans. Such turrets so often seen today on restored aircraft are, in reality, A-13As – a variant developed for Consolidated Aircraft. As was common with surviving WWII equipment, the reason A-13As are so prevalent is because they were still on the production line when the war came to an end. A large cache of them were repurposed for the 1970 film Tora! Tora! Tora!, being sawed off at the top so as to affix to the B-17s’ bellies without significantly altering the aircraft.

The Army had every intention of outfitting the B-17 with an externally fed ball turret, with Briggs planning to introduce the A-2B. However, Boeing blueprints do not even acknowledge the A-2B’s existence and no A-2B components, to our knowledge, have ever been located. The A-2B and A-13A were part of a program to give ball turret gunners more room, the goal being to allow the wearing of a Type B-8 parachute. The removal of the ammunition magazine freed a considerable amount of space and the ball was redesigned with a new fuse box, hand control, and window layout. There was discussion of casting these later turrets in magnesium but we do not have enough information to confirm if this took place. The A-13A only saw limited service in the Pacific theatre, being found on B-32 Dominators, PB4Y-2 Privateers, and late-B-24s sold to India and Australia.

An easy way to differentiate early ball turrets (A-2, A-2A, A-13) from late ball turrets (A-13A) is the window arrangement.

The other myth that should be noted is the use of an external oxygen tank to feed the ball turret. This was only found on the A-2 aboard the B-17.

While we do not have information as to the exact serial numbers where it took place, we know the change from constant-flow to demand-flow oxygen systems occurred sometime in the A-2 series. This was accommodated with a surprising degree of ease. However, unlike the A-1 upper turret, it took some time to alter the ball turret’s hanger assembly to accept oxygen from the aircraft’s supply. This was finally accomplished with the A-2A variant. In fact, there is documentation showing a plethora of field modifications to outfit the A-2 with multiple F-1 oxygen tanks, with some even mounting the larger G-1 tank in its stead – many with external pressure gauges so the crew could keep an eye on the ball turret gunner’s oxygen supply.

Upper left, an A-2. Upper right, an A-2A. Lower left, an A-13. Lower right, an A-13A.

Some of the major design changes in the A-2/A-13 series:

A-2 (exact serial range unknown)

Barriers are placed shielding the gunner from his weapons on either side.

A-2 (exact serial range unknown)

Constant-flow oxygen system at some point replaced with demand-flow system. Reliant on external tank feed until A-2A, which connected the turret to the aircraft’s oxygen supply.

A-2

A-13 (1-967)

End bells have plexiglass covers to improve aerodynamic flow.

A-2

A-13 (1-1961)

Ammunition magazine cover is made of cast aluminum. Replaced with stamped steel type.

A-2

A-13 (1-523)

Fuse box uses cannon plugs. Replaced with direct lines through rubber grommets.

A-2

A-13 (1-851)

Hand control has large nubs below each grip. Subsequently shortened.

A-2

A-2A (1-128)

A-13 (1-3186)

Oxygen regulator and pressure gauge mounted to turret wall. There is no oxygen flow gauge. Replaced with regulator mount under seat plate (beside suit heater) and proper oxygen panel.