I hesitated to post this, as the seller has not yet sent the information for us to pay him. Maybe he wants to donate! Ha! Still, I did not want to keep everybody waiting…

Our followers might recall the recent progress we made on the center console panel that sits between the two pilots. There was a large hole in this panel, which is there to accommodate the Cowl Flap Control Panel. This panel was not made by Boeing but as Government Furnished Equipment (GFE).

Two companies made this panel: Adel Precision Products of Burbank, California, and Gladden Products of Glendale, California.

Formed in 1938, Adel (a portmanteau of founders Adler and Ellinwood) specialized in aircraft wire fasteners and clips, expanding into general aviation components during the war. In 1950 Adel merged with Enterprise Diesel Engines, the current incarnation being Cooper Machinery of Houston, Texas.

Gladden Products was formed from the ashes of Kinner Airplane & Motor, which went bankrupt in 1937, with OW Timm Aircraft purchasing the aircraft division. Motor division chief John Gladden achieved great postwar success with the Gladden Mustang scooter, first released in 1947. Eventually rebranding as Mustang Motorcycles, the company collapsed in 1965, in large part due to competition from Honda.

The panels are extremely similar and are both quite large and heavy. This is because they are hydraulic.

The hydraulic system on the Boeing B-17 is one of the most often misunderstood aspects of the airplane. The only systems on the B-17 that were hydraulic were the brakes and the cowl flaps. Virtually everything else was electric.

(One minor exception is the two powered turrets, as they used hydraulic transmissions, powered by electric motors.)

This was in stark contrast to many other large aircraft of the period. The Consolidated B-24, for example, had hydraulic wing flaps, bomb bay doors, brakes, and landing gear. One might argue that the superiority of one system type over the other is down to individual preference, however it is worth noting that predominantly hydraulic aircraft suffered more issues with leakages, freezing, and fires. Likewise, purely hydraulic turrets were known to ‘creep’ when fired for extended periods.

The seller of our cowl flaps panel was nice enough to insist upon payment-upon-receipt, saying we could return the panel if not satisfied. The first panel he sent was a Gladden-type panel and, while it was in superb condition, our references showed that it was not as common on F-model B-17s as the Adel-type. So we exchanged it. It took some time getting them switched out over the holidays, but we now have a NOS Adel-type cowl flap panel for Lucky Thirteen.

A superb and exciting addition. Special thanks to Rian Olsen for alerting us to this piece back in December!

The newly-arrived Adel-type Cowl Flap Control Panel. While not visible in the photo, the service tag is dated 1 January 1945.

The dab of white paint beside the relief valve shows that this piece has been inspected.

Photo taken 22 January 2022.

The back of the newly-arrived Adel-type Cowl Flap Control Panel. Plastic caps cover the attachment points for the hydraulic lines.

Photo taken 21 January 2022.

A wartime advertisement for Adel Products.

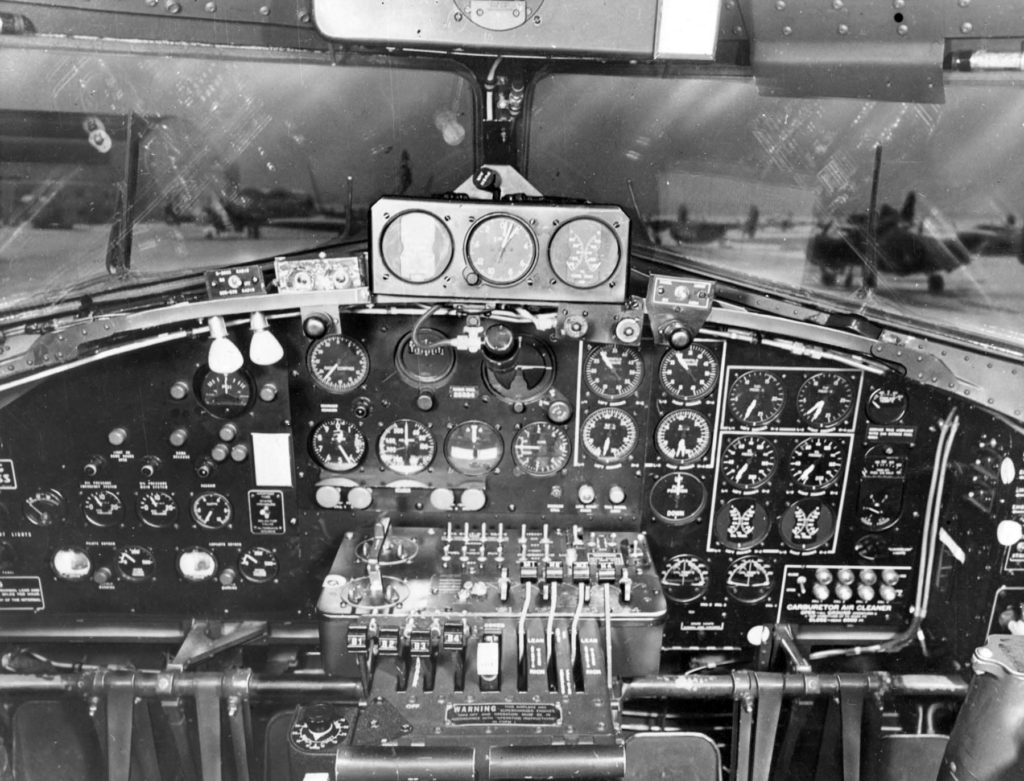

We use this picture often but it is a good one. An F-model from a production run earlier than Lucky Thirteen.

An Adel-type Cowl Flap Control Panel is visible here.

The Gladden-type Cowl Flap Control Panel.

Note the differences between the Gladden and Adel type panels: size of engine markers, decorative border, location of manufacturer’s label, location and shape of relief valve, location of speed control, and location and type of mounting screws.

Photo taken 18 December 2021.

The back of the Gladden-type Cowl Flap Control Panel.

Photo taken 18 December 2021.

A 1950 advertisement for the Gladden Mustang.

I apologize for the watermarks – could not find a clean version of this photo.

This G-model B-17 appears to have been used for parts as several pieces are missing. However, a Gladden-type Cowl Flap Control Panel is visible here.

The cowl flaps of Our Gang (42-5069, 91BG) are visible on the #2 engine, beside artwork of a sexy gremlin girl. “Gremlins,” it was said, were responsible for mechanical breakdowns, tearing apart components when mechanics were not around.

Our Gang was lost over Schweinfurt on 17 August 1943. Lucky Thirteen was present that day, suffering damage to her waist compartment, severely wounding gunners SSGT L. Corwin Miller and SSGT John F. Schimenek.

Our Gang was noteworthy as having the same navigator’s table setup as on Memphis Belle, where the table was installed on the opposite side as the factory installation. The NMUSAF has surprisingly gotten this wrong in the Belle‘s restoration.

The Adel-type Cowl Flap Control Panel arrived still in its original heavy wrapping. We had to carefully clean away the protective grease after unwrapping.

Photo taken 21 January 2022.

The Cowl Flap Control Panel cannot be mounted in place until the housing for the panel is ready. There is a T-extrusion that runs across underneath, which the upper part of the cowl flap panel mounts to.

Just to give an idea of what it will look like though, Megan is holding it here for our followers. She is wearing gloves because it is HEAVY.

Note that the landing gear and wing flap switches have not been installed yet. Rian Olsen has offered to provide the switch guards to these switches. Thanks Rian!

Photo taken 4 February 2022.

Back in November we were contacted by Steve Hester in Falls City, Texas. Steve reached out to us about our work on the Type C-1 autopilot system, offering to help find some parts that we needed. Steve is a great guy and surprised us with an offer of some stuff that he “needed to get rid of.” We decided to wait until after the holidays, and now Steve’s box of “stuff” is here.

It is some wild stuff.

Check out the photo descriptions to see some of the pieces Steve has donated to the project.

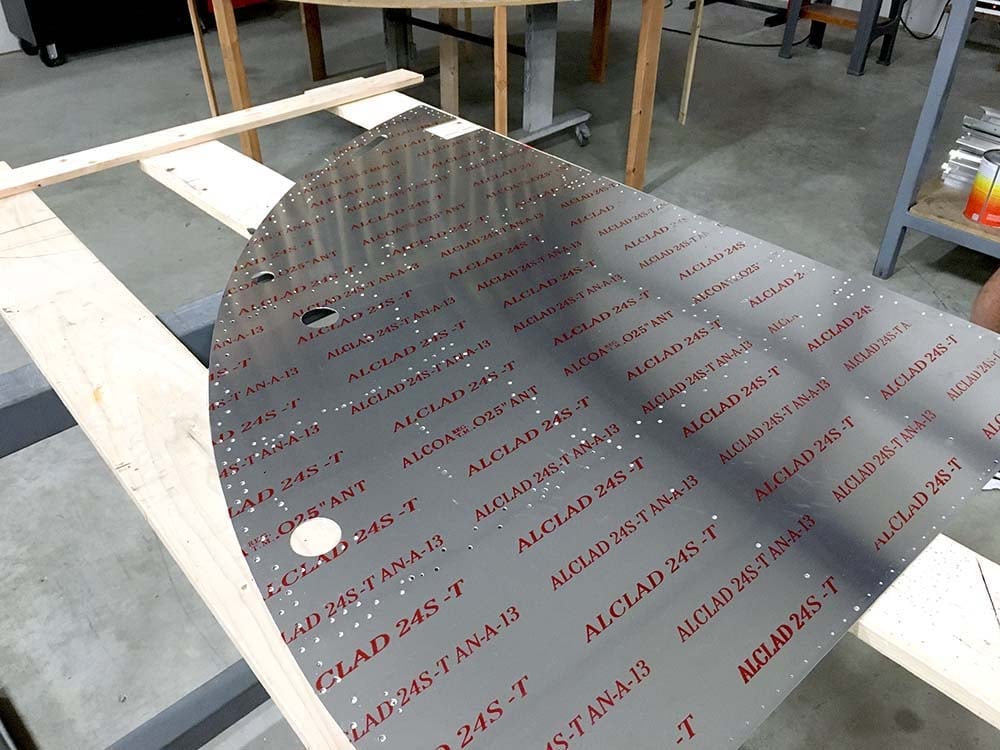

In other news, we remain hard at work despite the wintery weather. Now that the skins for Station 5 have had their ALCLAD markings stamped, Ray is working to dip its structural pieces in Zinc Chromate. To explain: while wartime B-17s had unpainted interiors (outside of the cockpit), it was still necessary to put some kind of barrier between differing metals to prevent corrosion. Douglas Aircraft – who manufactured Lucky Thirteen under Boeing license – tended to dip their ribs in Zinc Chromate. We are replicating that process.

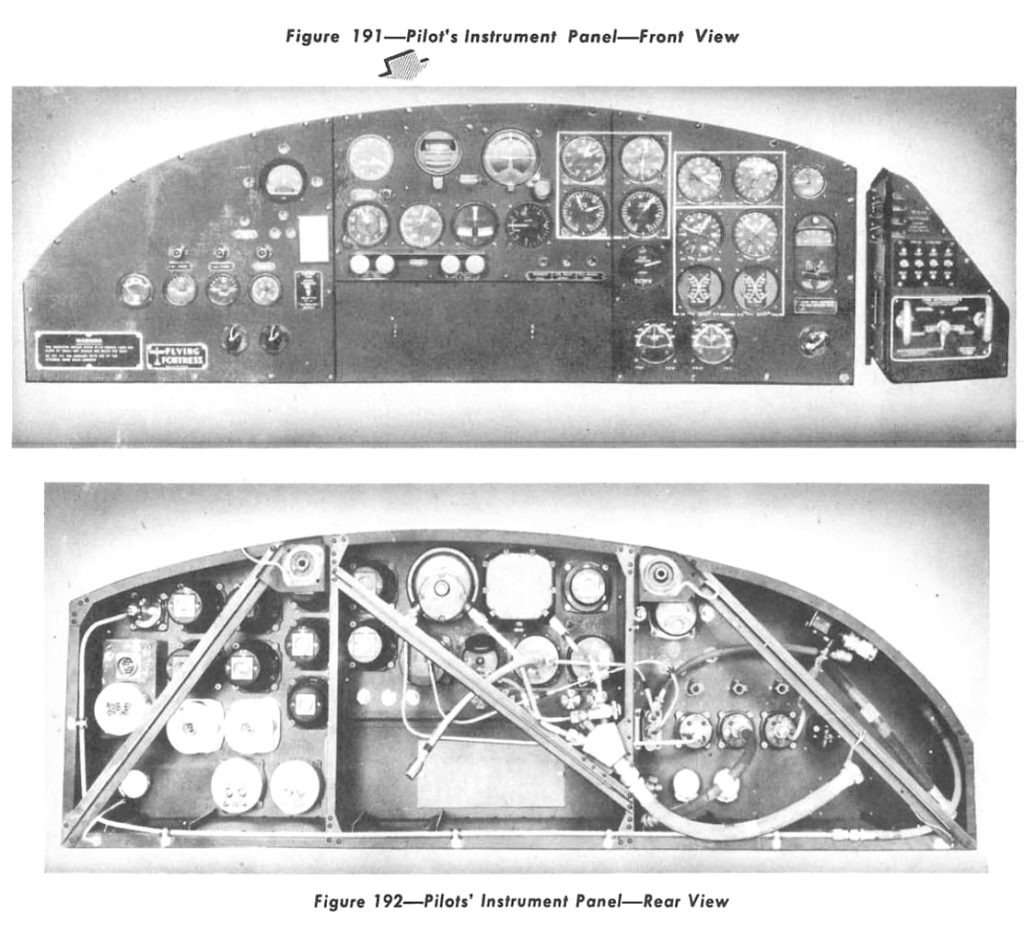

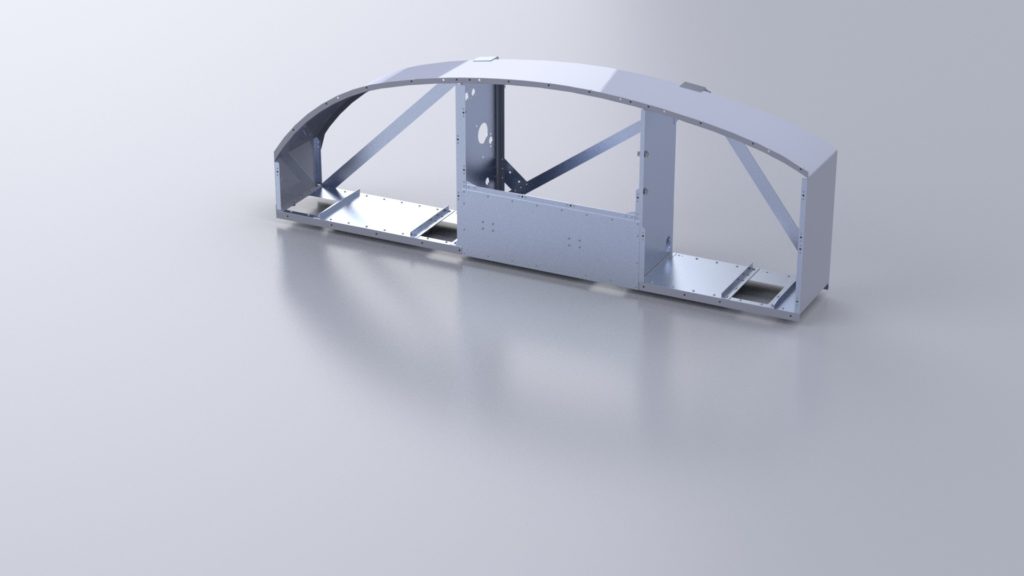

Meanwhile, Bob Hachmann is hard at work on the instrument panel housing. You might recall that we cut out a wooden mockup of the instrument panel face. This panel serves multiple functions, checking curvature, testing router bits, and holding gauges in place as we find them. The wartime panel was made of phenolic (i.e., Micarta), and in the interest of safety, we are going to wait to cut the finished panel faces until the housing is finished. G-model B-17s used a wooden panel housing, while older ones used an aluminum housing. Bob CAD modeled this surprisingly complex piece and has already built a wooden form for its construction. This will be a delicate process, but we look forward to seeing Bob’s work as he moves forward!

If you would like to help complete the cockpit instrument panel for Lucky Thirteen, there are still some gauges, switches, lights, etc. that we are in need of. The Instruments section of our Parts Drive page serves as a handy reference here. The most important gauges at this time are two C-14A Fuel Pressure Gauges (0-25) and one E-10 Tachometer (0-35) – both are which should have dual needles labeled “L” and “R.“ There are other gauges we would love to replace if we could find better examples of, as well. Preference is given to those gauges whose markings glow green when placed under a UV or black light, as this was standard for the vast majority of US gauges.

An incredible collection of Typey A-8B Oxygen Masks donated by our friend Steve Hester. I have never seen so many of these in one place before…

The Type A-8B was standardized by the US Army on 1 May 1940. Designed by the Mayo Clinic, this mask was designed to be used with constant flow oxygen systems. The A-8B suffered from narrow fittings that easily clogged with frozen saliva, and the constant flow of oxygen limited time at high altitude. Because of these deficiencies, constant flow systems were slowly replaced by demand flow systems (which only pumped air when the wearer breathed in) throughout 1943.

These A-8Bs are all postwar, with markings indicating manufacture in the 1960s. Most likely these were used for training purposes. The rebreather bags on these A-8Bs have broken apart with age over the years – which is common.

Photo taken 20 January 2022.

CPT Jim A. Verinis (91BG) wears an A-8B oxygen mask in early-1943.

The biggest difference between wartime and postwar A-8Bs are the straps. Wartime A-8Bs had leather straps, while postwar A-8Bs had cloth ones.

A Type A-14B oxygen mask donated by Steve Hester.

Wrap-around oxygen masks were the obvious solution to the narrow fittings on the old A-8B. While several masks were designed to wrap around the face, none were as successful as the A-14. Standardized on 1 July 1943, the A-14 was so efficient that it remained standard issue until 1954 – and even then, stocks of them remained in the US Air Force well into the 1980s.

Still in its original envelope, this mask is a postwar example with additional fittings not found on WWII masks. This one is dated 1977.

Photo taken 20 January 2022.

An airman wearing an A-14 Oxygen Mask.

Steve’s newly-donated Type M-3 Flak Helmet.

Most aircrew combat casualties were the result of anti-aircraft artillery, or “flak.” Because flak resulted in small pieces of low velocity shrapnel, airmen took to wearing M1 infantry helmets over their flightgear for protection. Various modifications were tried so these helmets could more easily accommodate headphones, and the M3 was the most common of these.

Photo taken 20 January 2022.

A pair of Consolidated B-24 waist gunners wearing M3 Flak Helmets.

Note the gunner in the back – he is wearing a flak jacket over his F-1 heated suit. Developed in October 1942 by Wilkinson Sword, the “flak jacket” sewed together some 500 steel plates between layers of canvas, weighing over 30 lbs. Today Wilkinson Sword is the manufacturer of Schick shaving razors.

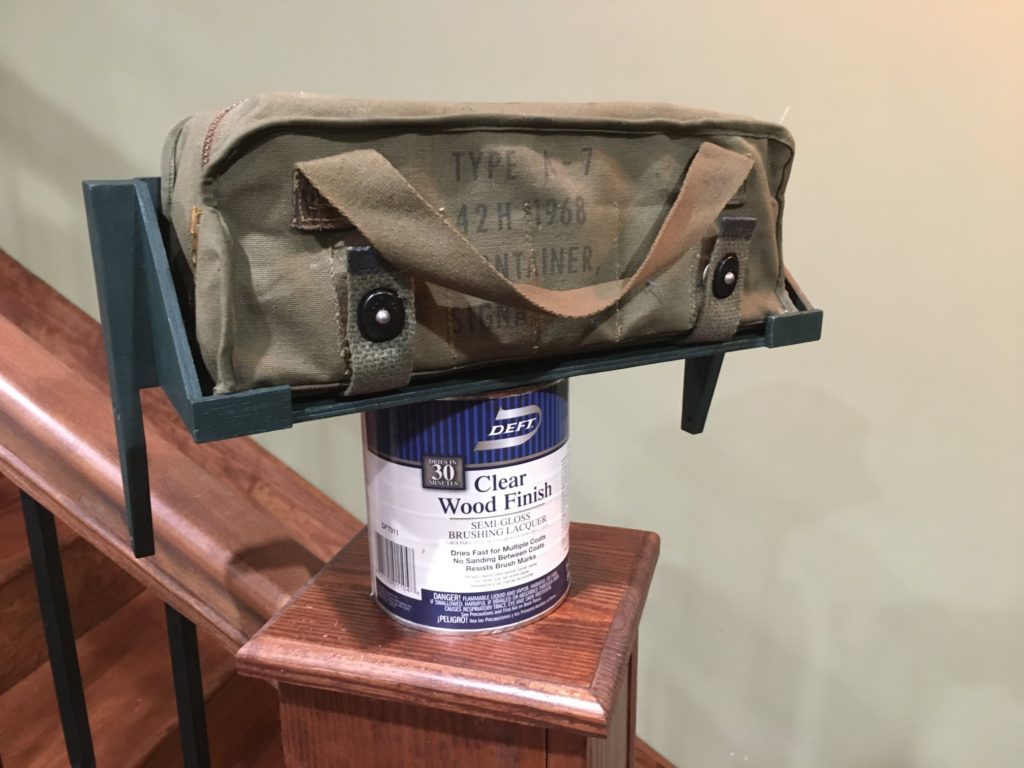

Steve’s newly donated AN6505-1 Kit Bag.

Photo taken 20 January 2022.

Airmen of the 92BG walk away from their B-17 after a sortie, many of them carrying AN6505-1 kit bags.

Because of the extra weight and tight spaces, it was not uncommon for aircrew to only finish putting on their gear once in position onboard.

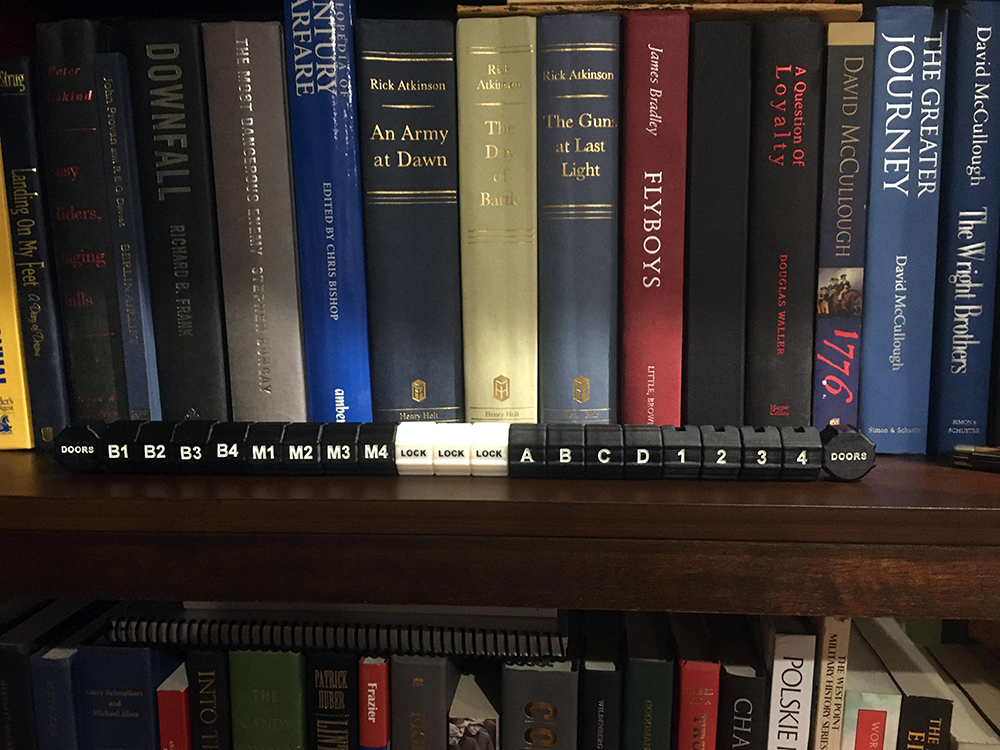

Steve’s newly-donated dimmer lights.

With the exception of the one wrapped in paper (top left), all of these are incorrect for our project. These dimmer lights have black plastic knobs rather than silver metal ones.

Photo taken 20 January 2022.

Snow outside the hanger.

Photo taken 18 January 2022.

The ribs and supports for Station 5 are readied to be dipped in zinc chromate.

Station 5 was the back wall of the bomb bay (forward wall of the radio compartment).

Photo taken 18 January 2022.

The ALCLAD markings applied to one of the two Station 5 skins.

Photo taken 2 November 2021.

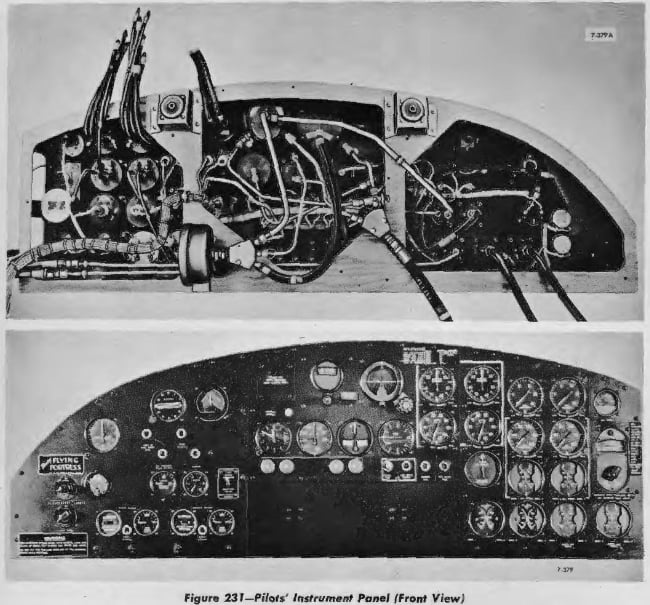

A manual illustration of an early-F instrument panel. The rear view shows the old-style metal housing.

Early B-17 panels used phenolic placards as labels instead of printed markings. Also note the engine fire-extinguisher panel on the far right. Lucky Thirteen was built during a short period where these panels were omitted. Due to the unpopularity of this decision, these panels were returned in the G series.

A manual illustration of a G-type instrument panel.

Note the wooden housing used on later B-17s.

Bob’s CAD model of the instrument panel housing for Lucky Thirteen.

Bob’s forming buck for the instrument panel housing.

His workshop is a lot cleaner than mine! Ha!

Photo taken 7 January 2022.

On 3 January we shared a post from our friend Marc Poole, who donated an incredibly rare jacket to the project. Marc is an art professor at Mississippi Gulf Coast Community College and is also the originator behind the 384BG’s superb website. Now that the jacket is here, we wanted to share some pics!

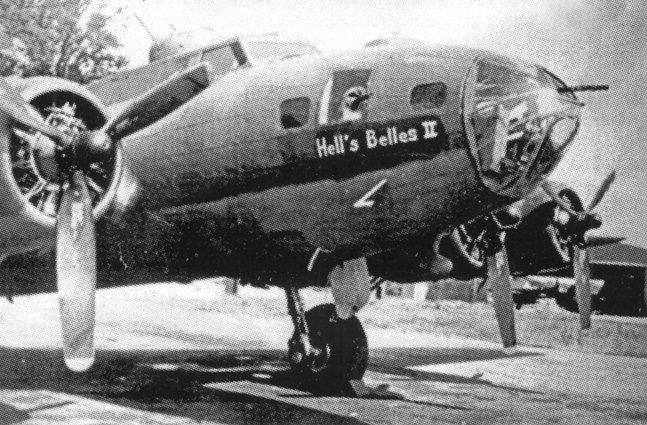

Marc’s grandmother’s first cousin was 1LT Johnny A. Butler of the 384BG. Butler was originally the 546BS Operations Officer but later transferred to the 547BS as a pilot. Butler flew 24 combat missions before his aircraft, Hell’s Belles II (42-5849), was lost on 16 September 1943 – ten days after the loss of Lucky Thirteen. Three of the crew were killed but Butler evaded capture, being smuggled into neutral Switzerland.

One of Marc’s early projects with the 384BG was recreating the unit’s patches. Marc took the time to reproduce the patches for each squadron – the 544BS, 545BS, 546BS, and 547BS – by carefully measuring and referencing wartime originals. Predominant practice was to wear a painted-leather squadron patch on the left breast of the wearer’s jacket, though embroidered cloth types became more common as the war progressed. Marc purchased this jacket from an estate sale as it carried the remnants of the elusive group patch, which was primarily worn by headquarters personnel.

This jacket belonged to 1LT Elwin R. Kircher, who was the 384BG Armament Officer from 4 April 1943 to 11 December 1943. The jacket is an A-2 Flight (Summer), a type first introduced in 1931. Though the jacket was officially phased out in late-43/early-44 as part of an effort to get away from leather flight gear, the A-2 was so popular that airmen could be seen wearing A-2s as late as the Korean War.

Though we do not know the circumstances of Kircher’s transfer, Kircher was first moved to the 482BG and later to the US 8AF Air-Sea Rescue Squadron in late-1944. The yellow patch on the left breast is from this unit. Kircher was apparently proud of his time in the 384BG, as he moved its patch to his right breast and kept it there after leaving. The remnants of the group patch are still visible.

Marc’s recreations of the 384BG’s squadron patches can be purchased in an embroidered format from the 384BG. Also available is a group patch, based on the latter-war layout, and a Triangle-P patch based on the latter-war 384BG tail insignia. If anyone should come across a leather 384th group patch from the war, be sure to let either us, Marc, or the 384BG know!

Since hangar space is at a premium, we really do not have the room to put this piece on display as of yet. Things may change as we expand the upstairs walkway, but more than likely, we won’t be able to display this piece for some time. We have been offered some amazing artifacts over the last couple years, some of which we have stored here, and others we have asked donors hold onto. We would love to one day have our own proper museum facility, and believe me, we have talked a great deal about the sorts of displays we would like to set up. But this all takes time and money – and we have a lot of other stuff to do before we get there! Until then, we have ordered a special box designed for the expressed purpose of storing vintage clothing at museum-quality safety standards. As such, Kircher’s jacket will live on for generations to come, safely kept near the same B-17 it administered all those years ago.

Our sincere thanks to Marc for this amazing donation. If you would like check out some of Marc’s paintings and other artwork, be sure to visit his Facebook page.

Marc’s newly donated A-2 jacket from 384BG Armament Officer 1LT Elwin R. Kircher.

The jacket was found at an estate sale in Olathe, Kansas and is a size 38 made by United Sheeplined Clothing of Long Branch, New Jersey. The jacket was in poor shape, already dry-rotting from improper storage. Marc put a lot of work into conditioning the jacket to restore its original color as well as a degree of pliability.

Photo taken 8 January 2022.

Marc’s newly donated A-2 jacket from 384BG Armament Officer 1LT Elwin R. Kircher laid out on the table.

Photo taken 8 January 2022.

CO 384BG COL Budd J. Peaslee poses with the crew of Black Ghost (42-5843) on 28 June 1943. Black Ghost was the lead aircraft this day. Like Lucky Thirteen, Black Ghost was lost on the 6 September 1943 strike against Stuttgart.

Peaslee is standing on the back row, second from the right. Note the 384BG patch on his jacket, just like the one on the Kircher jacket.

Peaslee can easily be allotted with Curtis LeMay, Jack Slessor, and Pete Quesada as one of the truly great air leaders of the Second World War. He is perhaps best known for the creation of “Scouting Forces,” which first saw action on 16 July 1944. Similar to the RAF’s Master Bomber program, Scouting Forces worked by flying ahead of the strike force, checking on weather patterns and enemy opposition, and providing critical feedback to the following formations. By doing so, the scouting forces could call for course corrections and changes in target selection, with preference given to those targets with the clearest visibility.

The remnants of Kircher’s 384BG patch. Imprints from the original markings are still visible.

Photo taken 8 January 2022.

A pair of patches based on the artwork Marc recreated.

The patch on the left is from the 546BS – Lucky Thirteen‘s squadron. The patch on the right is the latter war variant of the 384BG patch. As you can see from Kircher’s jacket, the older patch was somewhat more squat in appearance.

Photo taken 19 January 2022.

Hell’s Belles II (42-5849, 384BG). This is the aircraft flown by 1LT Johnny Butler – Marc’s grandmother’s cousin – when lost on 16 September 1943.

Despite being one of the 384BG’s original complement, Hell’s Belles II only completed 11 combat missions.

The crew of Helle’s Belles II (42-5849) shortly after arriving in the UK.

From left to right:

(Back row) – 2LT Herman Wollenweber, Jr. (Co-Pilot), 1LT Johnny A. Butler (Pilot), 2LT Joe W. Baggs (Bombardier), 2LT Ed J. Knowling (Navigator), SSGT Marion C. Rogers (Waist)

(Front row) – SSGT Burnia Martin (Waist), SSGT Armando N. Ordaz (Tail), TSGT Preston A. Davis (Radio), SSGT H. Joe Turlington (Engineer), SSGT Bill D. Wolven (Ball)

Wolven and Rogers were killed in action.

Kircher’s patch from the US 8AF Air-Sea Rescue Squadron.

In 1945 this unit was renamed the 5Th Emergency Rescue Squadron (5ERS).

If you look closely, you can see the stitching holes from where the 384BG was originally on this side.

Photo taken 8 January 2022.

1LT Don Armstrong of the US 8AF Air-Sea Rescue Squadron.

Note the round patch on his A-2 jacket.

“Z-Zebra” (42-7922) of the Air Sea Rescue Squadron.

The US 8AF Air-Sea Rescue Squadron (later renamed the 5th Emergency Rescue Squadron) flew its first operational sortie on 10 May 1944. The unit was formed to help take up the responsibility of rescuing downed aircrews in the weeks prior to D-Day. Up until this time, search-and-rescue operations were handled by the Royal Air Force.

Based at RAF Boxted with the 56FG, the unit was primarily composed of war-weary Republic P-47s. Standard practice saw a pair of P-47s patrol the English Channel during an 8AF strike. Should an emergency occur, the fighter-on-the-scene would drop two dinghies and a flare container, then circle the area until relieved by another fighter (who was kept on standby). This ensured that someone was with the downed airmen until time-of-rescue. By war’s end, some 938 airmen were rescued by the 5ERS.

A Consolidated OA-10 with the US 8AF Air-Sea Rescue Squadron. The OA-10 was the Army equivalent of the Navy’s PBY Catalina flying boat. Note the white paint scheme, characteristic of aircraft operating in the North Atlantic.

Because of their size, 8AF OA-10s were based at RAF Halesworth with the 489BG.

We wanted to give a shoutout to our friend Robert Kropp at 4Y-2 in Phoenix, Arizona.

Robert is a great guy and part of the team behind PB4Y-2 N2871G (BuNo 66302). This aircraft is a Coast Guard veteran and they have done an amazing job restoring the old fire tanker back to her old colors. These guys are friends so, if they happen to be in your area, definitely go out and show some support – N2871G is certainly a beautiful aircraft!

In response to our post discussing B-17 interior door handles – as Kevin Davenport 3D modeled them for us – Robert dug out some old B-17 door handle assemblies and a bailout bell for Lucky Thirteen. Thanks Robert!

As it currently stands, we only need one more door latch and two more handles to have a full complement for the B-17F.

We also wanted to share the flare gun stowage assembly today. While we have covered this before, we have not been able to share pictures of the everything together until now.

The flare gun – or as it is sometimes referred to, the Very pistol – was a standard piece of equipment for all large US military aircraft. For most F-model B-17s, the flare gun was the Type M2, a short-barreled brass pistol with oversized grips. This pistol was discontinued in May 1943 due to its heavy recoil and requirement that it be fired through an open window. The M2’s replacement was the M8 – the flare pistol most of us are familiar with today. The M8 was designed to fire through a specialized fuselage port and could accommodate both long and shorts flares (the latter being made for the M2). The flare pistol for Lucky Thirteen was donated by Andy Rivera in October 2019 and was made by Eureka Vacuum. This pistol is accurate for Lucky Thirteen as she entered service in late-June 1943.

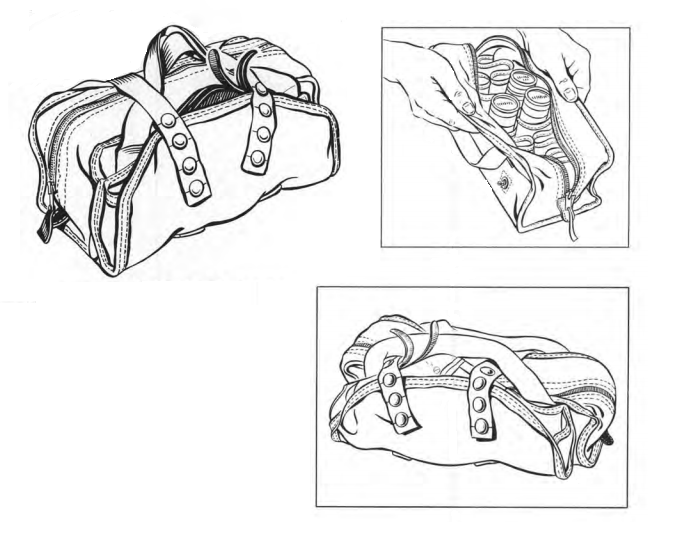

There were a wide variety of stowage arrangements for flares on the B-17, most of which were field modifications. The most common factory arrangement was a small wooden shelf mounted on the back of the pilot’s seat. This shelf held a Type A-7 Signal Flare Container, which could hold up to 18 flares, and a Type A-2 Flare Pistol Holder, which was designed to wrap around Type A-6 and A-7 containers, holding the pistol. A pair of straps, stapled to the shelf, held this bag assembly in place. We were fortunate to acquire a Type A-7 in February 2020 and a Type A-2 in June 2021. The shelf was finished in June 2019 and the straps for it finished in December 2021.

Andy actually donated several NOS flares along with his pistol, but in the interest of safety, we filled the container with wooden blanks. Don’t want somebody to load that thing and fire it when we aren’t looking! Chris Warne is working to make replica flares so, Chris, if you are reading this, we could certainly use some!

Having this arrangement restored is a big accomplishment for us as it is a piece of history that few have ever seen complete.

N2871G taking off back 2020, wearing her original Coast Guard colors.

Coasties never get the respect they deserve and N2871G is a beautiful tribute to their service.

Photo taken by zbubakaz

BuNo 59688 at Coast Guard Station San Diego.

Photo taken 18 October 1958.

Robert’s newly arrived B-17 door handle assemblies and bailout bell.

The assembly on the top left is from the cockpit door, as it has a spacer attached so the handle can fit through the armor plate. The screws and paint are not original.

Photo taken 21 December 2021.

The door handle to Station 6 (the back wall of the B-17’s radio compartment) is highlighted.

Kevin’s 3D printed door handle next to the wartime original. Looks like he got the CAD model perfect.

If anyone would like to use our CAD model to cast/mill some new ones, just let know!

Photo taken 17 December 2021.

1LT Bob M. Welty of the 398BG peers over the armor plate on his seat. The A-7 flare container and its shelf are highlighted.

Below this assembly sits an empty shelf – this is for the bomber’s Aldis lamp (or Signal Lamp). Our friend Stijn Claus has offered recreate this piece for us. Be sure to follow his amazing work at B-17 Flying Fortress Parts Project!

Keeping close to their Dodge WC-54s, paramedics await the landing of a 381BG B-17 after it has fired flares to indicate wounded aboard.

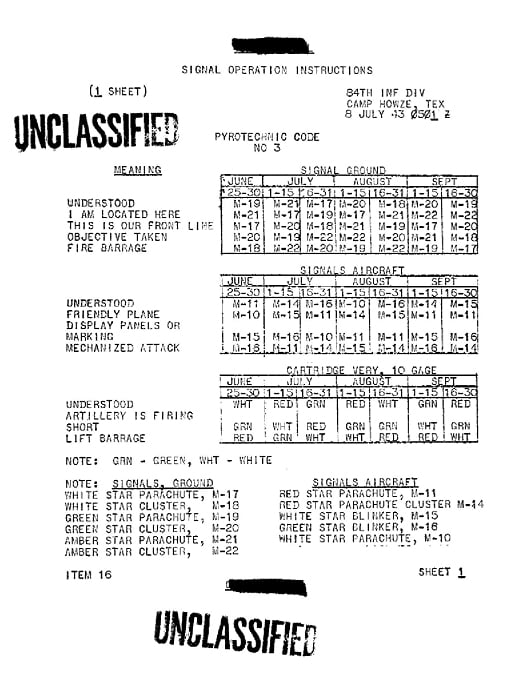

The signal is a double-star red.

Color classification for flares changed regularly throughout the war. This page is taken from the summer 1944 edition of the 84th Infantry Division’s “Signal Operation Instructions” handbook.

The only color constant for flares was red for emergencies.

The M8’s predecessor, the M2 flare pistol, which was discontinued in May 1943.

Cartridges for this pistol are distinguishable by their lack of a rim.

Wooden blanks, carefully turned to match the length and diameter of the correct flares, are packed in the A-7 flare container.

While the Army index states that the container can hold up to 18, an entire row must be removed for the gun holder to attach properly, bringing the number down to 12 – which was probably an ample amount.

Photo taken 20 June 2021.

A manual illustration of how the Type A-2 Flare Gun Holder wraps around the Type A-6 or Type A-7 Flare Container.

The Type A-2 Flare Gun Holder is wrapped around the Type A-7 Flare Container.

Photo taken 20 June 2021.

As per the blueprints, the Flare Shelf is made of 3/16 (3-Ply) Douglas Fir, with the spacers made of spruce and the arms of 3/8 Douglas Fir.

Photo taken 5 June 2019.

The straps for the flare container are ready to be attached. The straps have Lift-The-Dot Fasteners installed and the tips are dipped in bee’s wax, per Boeing spec.

Photo taken 3 December 2021.

These straps are stapled to the Flare Shelf, after which they wrap around the Flare Container and clip to its sides.

Photo taken 1 January 2022.

The Type A-7 Flare Container is clipped to the Flare Stowage Shelf.

Photo taken 1 January 2022.

The contents of the flare gun assembly for Lucky Thirteen.

Photo taken 20 June 2021.

The completed flare stowage assembly for Lucky Thirteen.

The arms of the shelf slide into the aluminum channels of the pilot seat frame assembly.

Photo taken 1 January 2022.

Some pics from Ray reflecting on how far things have come rebuilding the aft fuselage of Liberty Belle (44-85734) for the Liberty Foundation.

This update concerns Kevin Davenport and his Creekside High School CAD engineering class in Jacksonville, Florida.

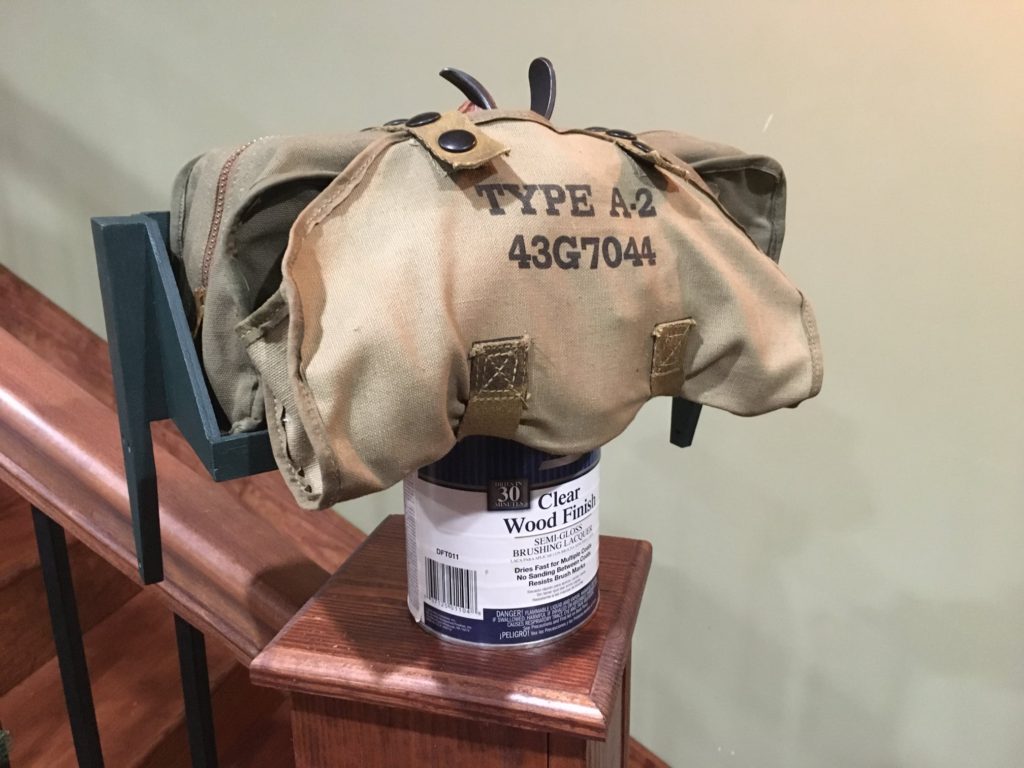

You might recall our update on the visit by some of his students to the National Museum of the Mighty Eighth Air Force back in September. In it, I mentioned how one student, upon noticing that a knob was missing from a control handle, produced a new one from his pocket and popped it on, curious to see if it would fit. That student was Garrett Alberts and, working with the original Boeing blueprints, he was able to model all 21 of the original knobs for Lucky Thirteen.

It took some time for us to locate the appropriate material, 3D printing several test runs before finally finding the right one. But just before Christmas, Kevin called me up to say that they were ready. They were printed by CAD engineer Dennis Dohogne, who added internal reservoirs to the knobs to prevent spillage when installed. Over the new year, I filled in the markings, applying phosphorescent paint to those knobs which required it. The guys here are thrilled with the finished product.

Special thanks to Garret, Dennis, and Kevin for their incredible work!

Rather than mail the knobs, we met at the hangar to discuss future plans for the top turret. Of immediate interest is the broken piece under the dome’s left gun port. Kevin is going to try and model this piece, as the alternative is to attempt to carve it by hand.

I should note that this broken piece is small and in no way affects the integrity of the dome itself. We just wish to be complete as possible.

Of a more long-term interest is reconstructing the power turrets in their entirety. 3D scanning will almost certainly be a must for the upper turret’s tub assembly and the ball turret’s ball. And of course, there is the issue of fundraising enough to purchase the parts necessary to fill them out. So, if anyone can help us with this effort . . .

As a minor aside, the switches have been installed in the center console panel. All that is left are the safety-covered switches and the cowl flap control panel – and both of those are on the way! We are currently checking out options to recreate the magneto switch linkage, either via casting or 3D metal printing (both of which tend to be rather expensive).

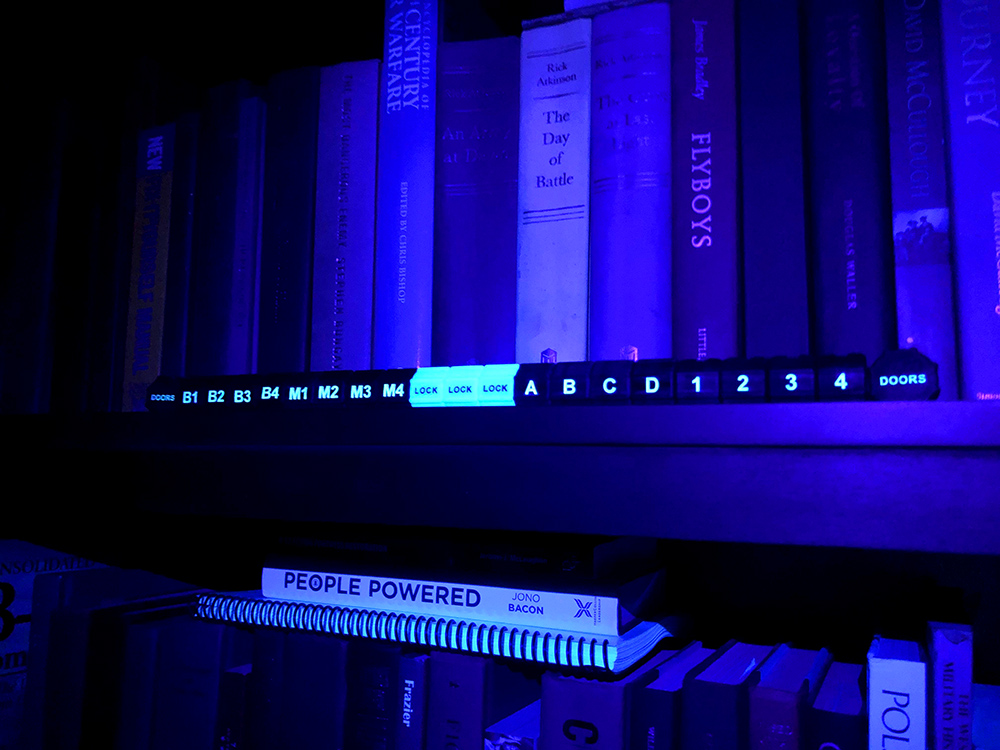

The finished knobs are lined up on my bookshelf.

Photo taken 31 December 2021.

Shining an UV light on the finished knobs to show off the phosphorescent markings.

Photo taken 31 December 2021.

The three finished Lock knobs. There is one for the turbochargers and mixture controls, one for the throttle, and one for the propellers.

Though it is not visible here, they are all printed in different locations due to the directions they face.

Photo taken 30 December 2021.

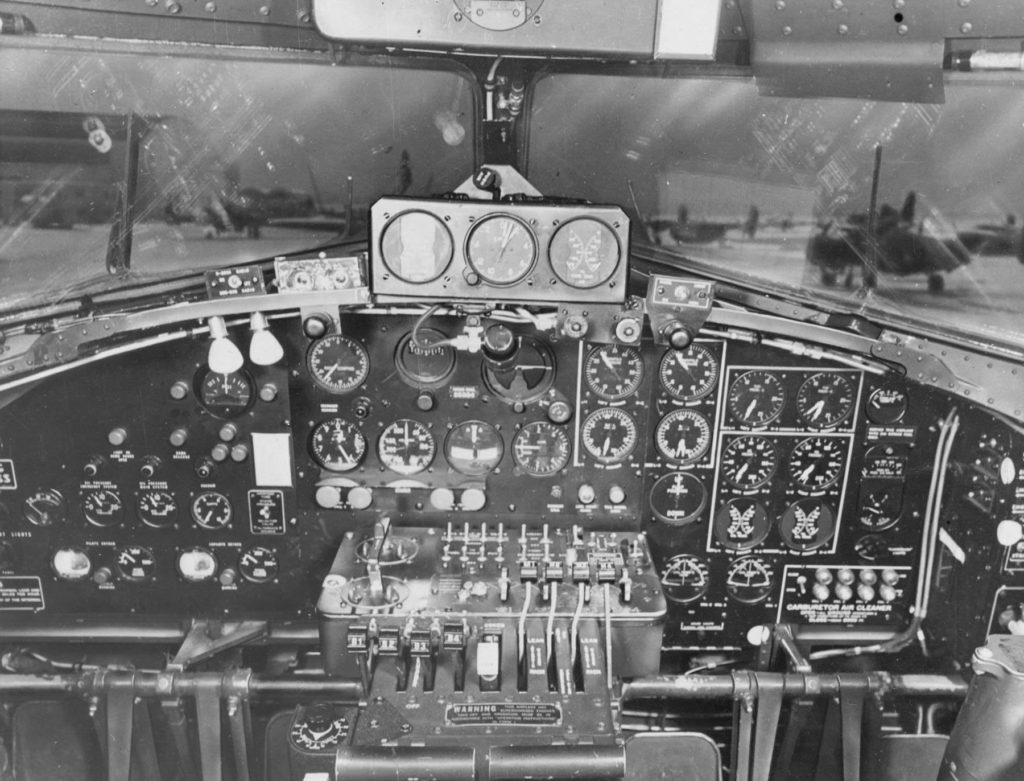

An F-model B-17 from relatively early/mid in the production run. The knobs for the turbochargers and mixture controls are visible here. The prop pitch levers were located under the throttles.

In the G series, the manual turbos were replaced with an electric control box with a big knob in the middle.

A manual illustration showing all the knobs mounted on the center console.

The center console panel, with its magneto switches and etc., is visible at the top.

A manual illustration of the intercooler levers and knobs, located to the right of the copilot.

Beside them is an indentation for the engine primer. This assembly was donated to the project by Albert Stix back in February!

A manual photo showing where the lever is located for the camera bay door.

The camera bay was located under the floor of the radio compartment.

SSgt Max Pearsall of the 381st Intelligence Squadron, USAF, donated the correct K-17 Strike Camera for Lucky Thirteen back in October. Now all that is left to find is the A-8 Mount, A-2 View Finder, and B-2 Intervalometer and the B-17F’s strike camera system will be complete.

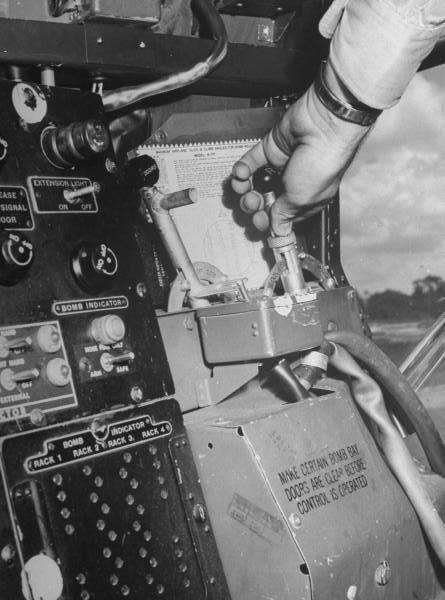

A rare photograph showing the bombardier’s controls in an older B-17.

The bomb arming lever control came preassembled, with Boeing simply adding a control for the bomb bay doors.

The knobs are printed and packed for their visit to Asheville, North Carolina.

Photo taken 22 December 2021.

The switches are installed in the center console panel.

Photo taken 6 January 2022.

A shot from a training film made using a B-17F from the same period as Lucky Thirteen. Note the silver screws.

This particular B-17F is 42-30641, an aircraft slightly younger than Lucky Thirteen. Notice that her mag switches are slightly different – these were made by Briggs & Stratton instead of Bendix Scintilla.

The students pose in front of City of Savannah (44-83814).

From left to right:

Nipun Warusawithana

William Bass

Brady Gannon

Garrett Alberts

Lauren Castillo

Kevin Davenport

and myself.

Photo taken 18 September 2021.

The newly arrived Type A-1 Upper Turret dome, sitting beside the fuselage jigs. The broken piece is visible on the right under the gun slot.

Photo taken 30 September 2021

Discussing the top turret. The dome is flipped over to inspect the curvature under the broken piece.

From left to right: Kevin Davenport, his wife Heather, Ray, and my wife Megan.

Photo taken 29 December 2021.

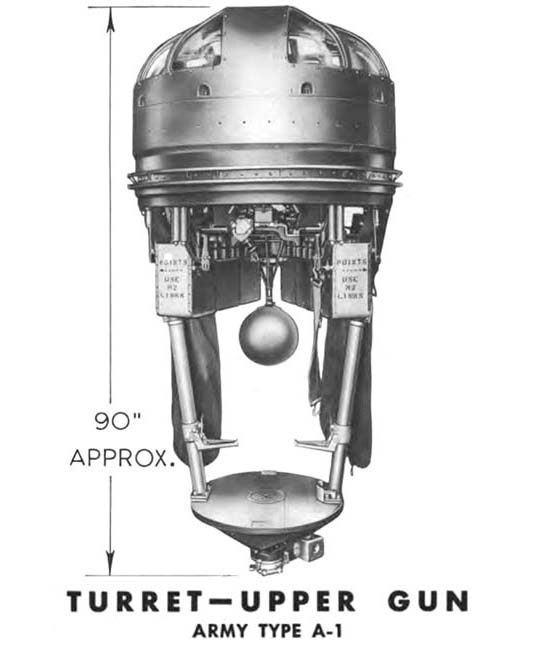

A manual illustration of a Type A-1 Upper Gun Turret.

Assuming we can raise the funds, we can locate originals for virtually all of the internal gears. It is the body which will likely have to be made anew.