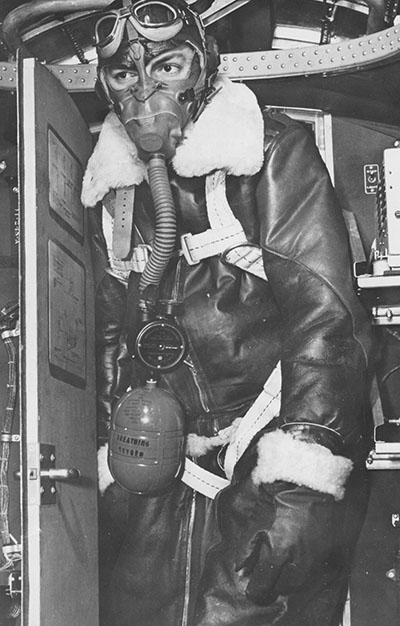

An airmen walks through the forward radio door of a late-B-17F just like Lucky Thirteen. His Type A-10 mask is connected to a Type A-4 Walkaround Bottle.

One of the most numerous components needed in Lucky Thirteen‘s restoration are the airplane’s oxygen bottles. A fully-restored B-17 should be full of them, as they were crucial to US air strategy in the Second World War. Higher altitudes offered better security than lower altitudes, so bombardment operations were often flown at the very limits of the aircraft’s altitude capability. The Boeing B-17 featured a service ceiling of 37,000 ft, and its contemporaries, the Consolidated B-24 and Boeing B-29, had service ceilings of 32,000 ft and 39,600 ft, respectively. This is not to say that American bombers always flew at their service ceilings; far from it – the weight of the bombs generally kept them from reaching such altitudes. However, taking into account that the Krupp 88 mm anti-aircraft cannon had a maximum range of 32,480 ft, flying at similarly high altitudes meant that anti-aircraft fire would be far less effective than if flying lower.

This dependence on high altitudes meant that effective oxygen systems were crucial. Above 15,000 ft the air is too thin to breath without assistance. The human brain begins to suffer damage after one minute without oxygen, the airman becoming tired, confused, and increasingly unaware of his surroundings. After six minutes, the brain damage is permanent, and after ten minutes, the airman falls into a coma and dies.

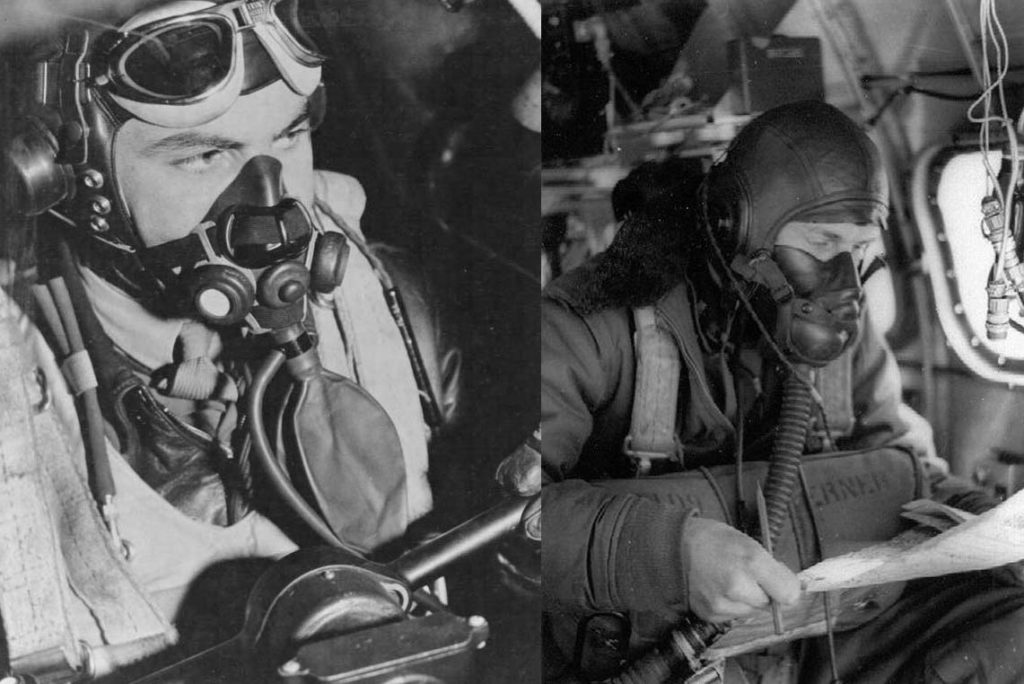

The two most common US oxygen masks in the Second World War: the A-8 (left) and the A-14 (right).

Despite all the discussion made amongst Air Corps leaders throughout the 1930s about the merits of high-altitude bombing, the US did not adopt a standardized oxygen mask until 15 July 1939. As such, US oxygen systems were constantly changing throughout the Second World War.

The two most common oxygen masks used by the US military during the war were the A-8 and A-14. The two masks were polar opposites of one another. The A-8, standardized on 1 May 1940, used a constant flow oxygen system, piping in air through a small hose and cycling the wearer’s breath through a rubber bladder. This design was not without limitations. A constant-flow system meant that oxygen was used at a very high rate. More importantly, condensation from the wearer’s breath tended to freeze in the mask’s fittings; since oxygen deprivation often went unnoticed by the sufferer, this could prove fatal. In fact, one of the more important tasks of the co-pilot was to call for an oxygen check every ten minutes, having the crew squeeze the ice out of their masks and acknowledge that they were still conscious.

The US experimented throughout the early years of the war with rubber wrap-around masks using a demand-flow oxygen system. Using a diaphragm that allowed air to flow only with the breaths of the mask’s wearer, demand-flow systems, with their wrap-around oxygen masks and large fittings, virtually eliminated the problem of frozen condensation. The most difficult aspect was developing a rubber mold with an effective, yet comfortable, air-tight seal on the face. Several masks were introduced, and the most successful of these, the A-14, was finally standardized on 1 July 1943. The A-14 proved so effective that it was the basis for all future US designs and remained standard issue until 1954, with examples still being found in US inventory as late as the 1980s.

Lucky Thirteen entered service during the same period that the demand-flow oxygen system was standardized. While construction was completed on 21 June 1943, she reported for active-duty on 28 July; as such, it is likely she was one of the first US bombers fitted with such an oxygen system.

SSGT James M. Abbott, 97BG, adjusts the F-1 oxygen tank that feeds his aircraft’s ball turret.

Surprisingly, it is not too hard to locate Second World War-type oxygen tanks. In the 1950s a common use for these old tanks was to convert them into air bubbles for your car, preparing for the eventual flat tire. For this reason, there are many Type G-1 oxygen tanks out there with makeshift handles and air gauges – easy enough to convert back to wartime spec.

If you are interested in helping Lucky Thirteen achieve her full complement of oxygen tanks, check out our Oxygen Equipment Parts Drive for information on what she needs

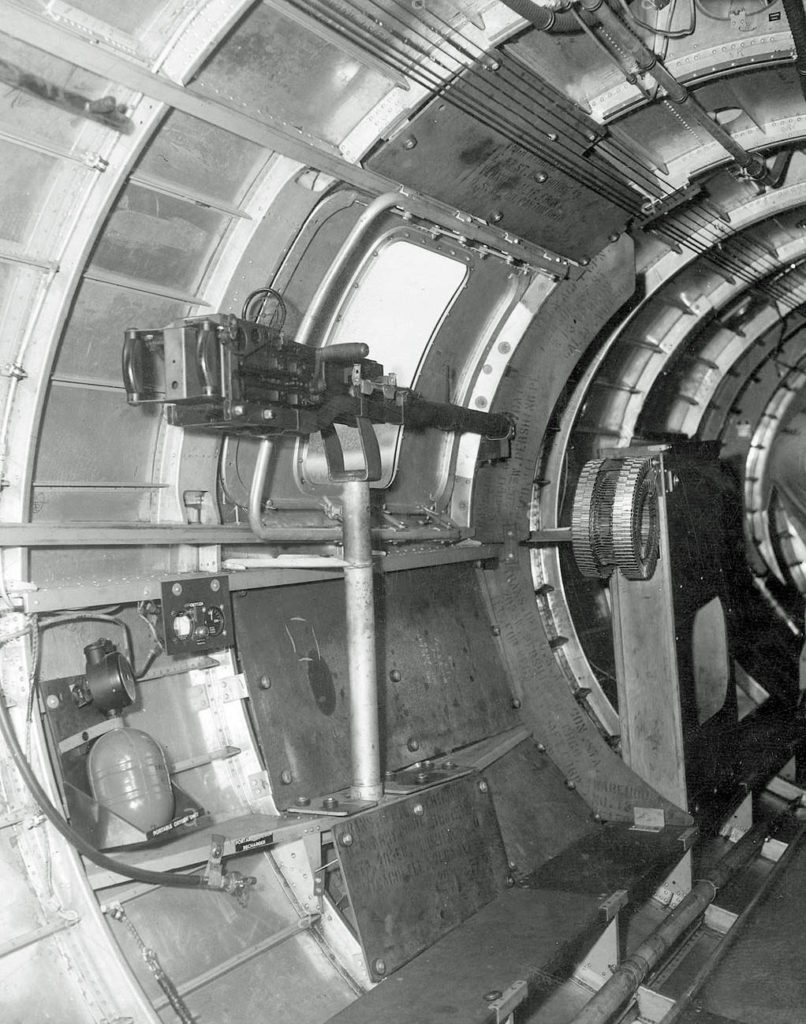

One of the eleven Portable Oxygen Bottle Stowage Brackets recreated for Lucky Thirteen.

Another of the carpentry projects saw the recreation of the thirteen wooden brackets that hold the aircraft’s portable oxygen bottles. These bottles were used whenever an airman needed to move from one part of the airplane to another, with most types offering eight minutes of use. As per the blueprints, the bracket is glued together using 1/4 Douglas Fir. The paint is a custom mix color-matched to Berry Brother’s Bronze Green No. 234G9. Contrary to the sickly green that most people associate with Second World War aircraft, this Bronze Green is in fact the most common color called for in the B-17’s finish manual (when paint is required at all).

A Type A-4 portable oxygen bottle sits beside the right waist gun in a late-B-17F. Lucky Thirteen‘s waist section was almost identical to what you see here.