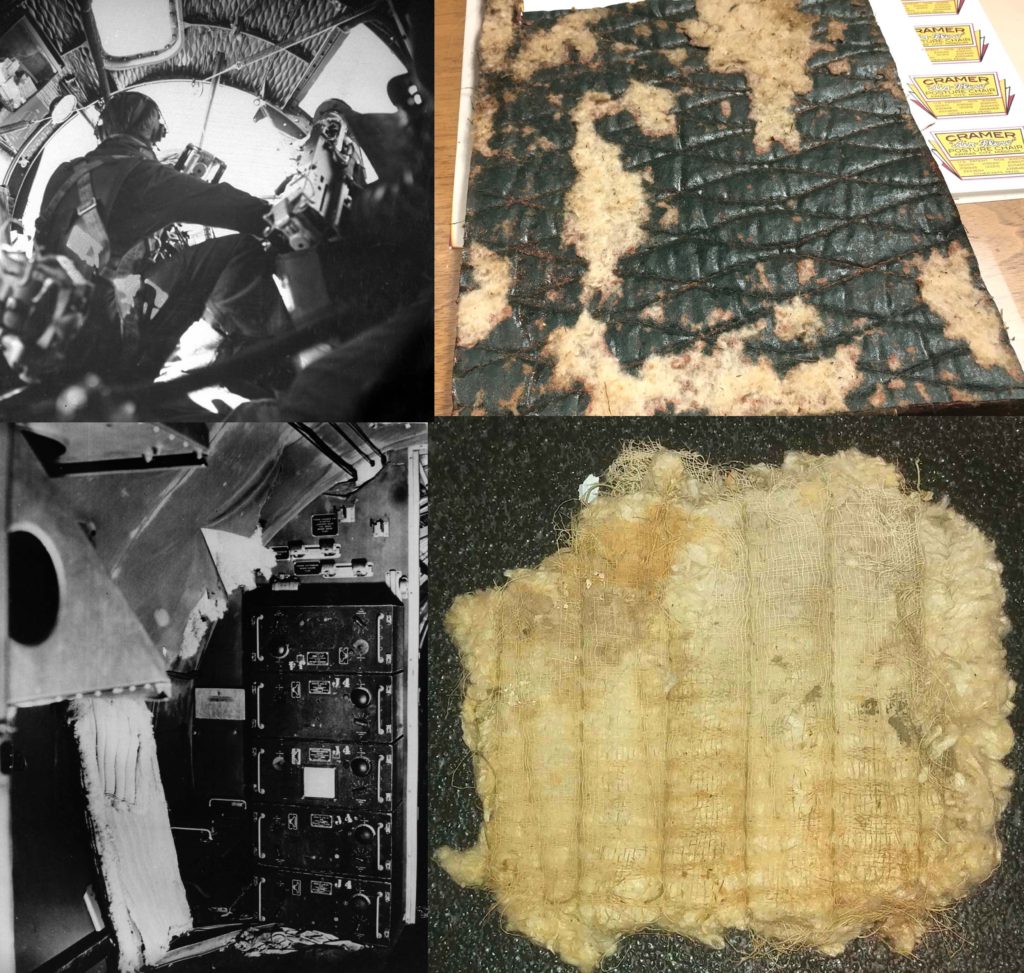

Looking a little worse for wear, the soundproofing in this B-17F’s nose is pulled back for maintenance.

When we began rebuilding Lucky Thirteen we did so knowing that at some point we would have to deal with the bomber’s internal fabric and insulation. Few surviving aircraft of the Second World War still have their internal fabric and even fewer are airworthy. Still, up until late in the F-series, the Boeing B-17 had three insulated, fabric-covered crew compartments: the nose, the cockpit, and the radio room. Having the same needs, Hangar Thirteen teamed up with the National Museum of the US Air Force to find sources capable of replicating this fabric for their restorations of Memphis Belle and Swoose.

The specifications for the B-17’s internal fabric and insulation were outlined in Report D-2887, a copy of which was obtained for us by the NMUSAF. Issued on 30 September 1940, it is worth noting that, despite a few revisions here and there, the report remained fairly consistent until 30 March 1945 when a four-page addendum was added detailing the optional use of fiberglass.

*Since this article was published, the COVID-19 pandemic halted this arrangement and the NMUSAF elected to place Memphis Belle on display without her interior fabric and insulation.

Greg Stathatos poses in the cockpit of B-17G Preston’s Pride (44-85738) in Tulare, California. Preston’s Pride – a veteran of the Bikini Nuclear Weapons Tests – may be the only surviving B-17 whose interior fabric remains untouched.

The reason for this addendum was wartime material shortages. American aircraft insulation was composed of a mixture of cotton, animal hair, and kapok. The largest producer of kapok at the time was Java, which fell to the Japanese on 12 March 1942. Since kapok was already in high-demand (it was also used in flotation devices), many aircraft manufacturers elected to recycle kapok from older airframes to maintain supply (the report acknowledges this). Incredibly, we were able to see this under a microscope by comparing samples taken from Memphis Belle (courtesy of the NMUSAF) and Preston’s Pride (courtesy of Greg Stathatos), as the latter samples were clearly made from recycled batts. Judging from the Report’s supplement, it would seem that Boeing was ready to experiment with fiberglass by the war’s last year.

Thankfully, kapok is more readily available now.

In general, the insulation material was sandwiched in layers of cheesecloth and glued to the skin between the circumferentials. Afterward, a layer of cloth, backed with another layer of insulation, was attached over as a sort of wall blanket. This insulation came in two types: a diamond-like stitch called Kwilko and a tube-like stitch called Tempak, neither of which still exist. The latter material was the more dominant type, as the diamond-like insulation was only used in the harsh curves forward of Station 2.

Insulation samples compared with photos taken from B-17Fs Winning Run (42-29944, 303BG) and Memphis Belle (41-24485, 91BG).

Pitifully few examples of these materials still exist in surviving B-17s. However, we are fortunate that the B-29 Superfortress – which was also made by Boeing – was set-up in very much the same manner. As such, Bock’s Car (44-27297), in particular, is a valuable reference, as Bock’s Car was placed on museum display immediately after her retirement.

The recreation of these materials takes a lot of work, as it involving the custom batting of felts and the dying of fabrics. If you wish to support this very important effort – be it in financial donation or volunteering your time and labor – do not hesitate to contact us.

And, if you are someone who enjoys such little details:

Click here to read a transcription of D-2887, which details the installation of fabric and insulation in the B-17 series.

The interior of Bock’s Car at the NMUSAF. Note the discoloration of the fabric, revealing the tube-stitching of the insulation underneath.