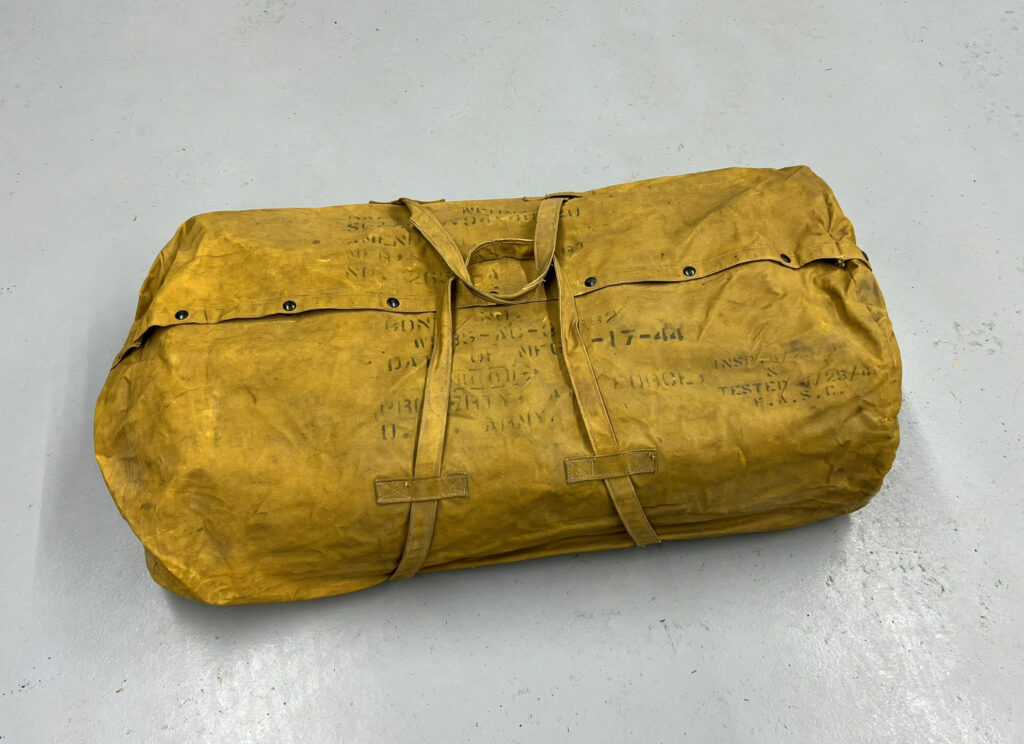

This week we have an exciting new arrival. One that, honestly, I never thought we would find.

We now have a life raft for Lucky Thirteen.

Photos taken 10 January 2025.

The standard Boeing B-17 carried a pair of five-man life rafts in a cubby above the bomb bay. This compartment was split into thirds, with the rafts taking up each outer section. The center section contained the life raft accessory kits. (Because of spacing issues, these kits were instead often kept in the aircraft.) The three sections were separated by baffles. A pair of release handles in the radio compartment, mounted in the ceiling just behind the upper hatch, opened the doors and automatically inflated the rafts.

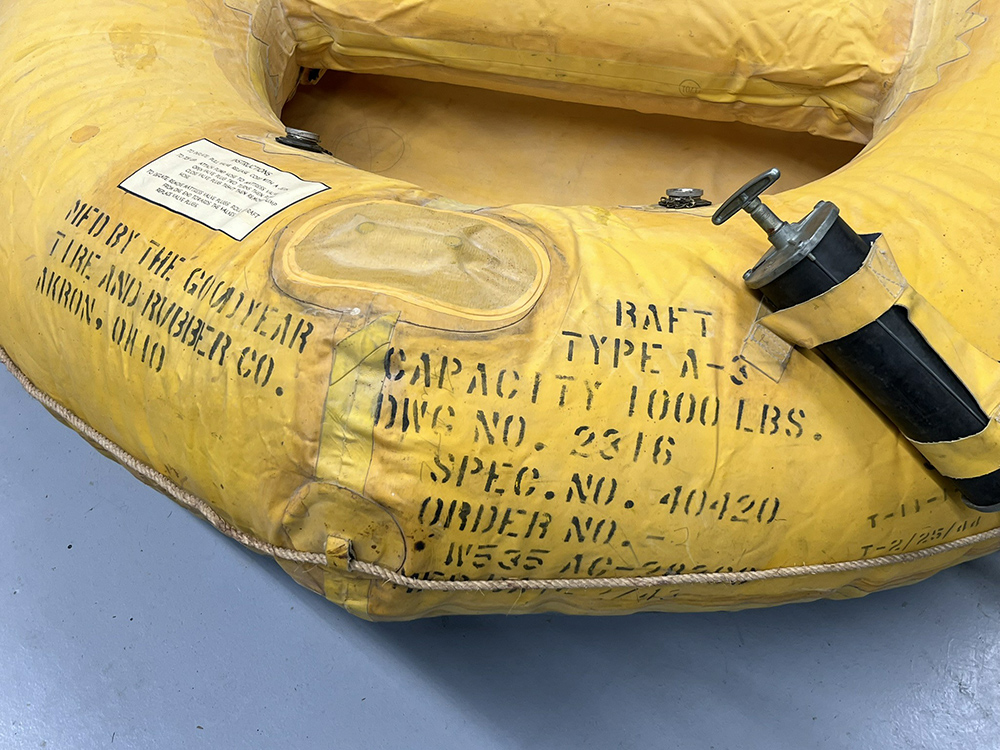

The life raft is a Type A-3 made by Goodyear Tire & Rubber of Akron, Ohio. The Type A-3 replaced the Type A-2 sometime in 1943 and this particular unit appears to be an early production model, as it shares more characteristics with the A-2 than what is generally associated with the A-3. These include the location of the accessory pockets and the lack of a rudder oarlock. The raft measures 9 feet 2 inches long by 5 feet wide and has a weight capacity of some 1,000 pounds – i.e., five 200 lb men.

The bag provides some additional information. This A-3 was completed on 17 January 1944 and tested by Fairfield Air Service Command (FASC) on 25 January. Interestingly enough, the original grounds of the FASC are now occupied by the National Museum of the US Air Force at one end of Wright-Patterson AFB.

Because this A-3 comes with a bag, it is unlikely that this unit was installed on a Boeing B-17. This is not surprising. Bagged life rafts were for those aircraft that lacked automatic life raft ejectors. Virtually all surviving wartime life rafts did so by being sold on the surplus market, and there was little interest in selling a raft without a way to properly store it. Papers included with this raft indicated that it was sold as surplus after the war by Rubbercraft Sales of New Haven, Connecticut.

Photo taken 10 January 2025.

Longtime followers may recall that we managed to acquire a Life Raft Accessory Kit Bag in March. Designed to be held in the center between the two inflated ribs, the accessory bags helped stow the large inventory designed to accompany each life raft.

The standard A-3 came equipped with the following:

Bailing Bucket

Boy Scout Knife

CO2 Inflation Cylinder with Pull Cable Release

Cord (40′)

Drinking Water Cans (x9)

First Aid Kit (Aeronautic)

Fishing Kit (x2)

Flare Gun with Flares (x5)

Floating Flashlight

Hand Pump

Match Box with Compass

Oars

Paulin (5’8” x 6’4″)

Paulin (7′ x 11′)

Police Whistle

Raft Repair Kit

Sea Markers (x3)

Signal Mirror

Sunburn Lotion

Type K Ration Kits (x9)

Wood Bullet Repair Plugs (x4)

Photo taken 6 March 2024.

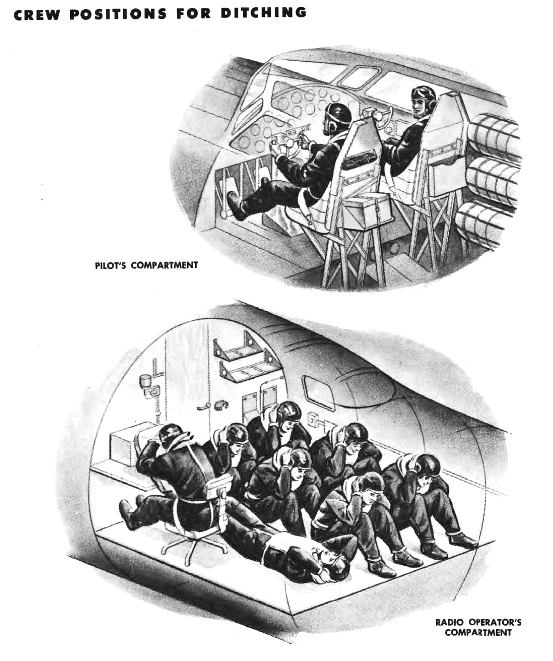

In the event of a ditching, the navigator would relay the present position of the aircraft to the radio operator, who would include it in his distress signal. The navigator would then destroy his flimsies (operational info printed on rice paper, so it could be eaten in an emergency) and head for the radio compartment with his maps and sextant. The bombardier would jettison the bombs (if any), ensuring the doors are closed when empty, and destroy the Norden bombsight. The recommended method was to empty his sidearm into the optics. The radio operator, steadily sending SOS signals, would set the BC-375 transmitter to the MFDF (medium frequency direction finding) frequency and the IFF to distress. He was also to eat his flimsies. The gunners were to throw overboard as much weight as possible, particularly ammunition, retrieving the Gibson Girl emergency radio and heading for the radio compartment. The entire crew, minus the pilots, gathered in the radio compartment for a ditching.

Manual illustration showing proper positions for ditching in the Boeing B-17.

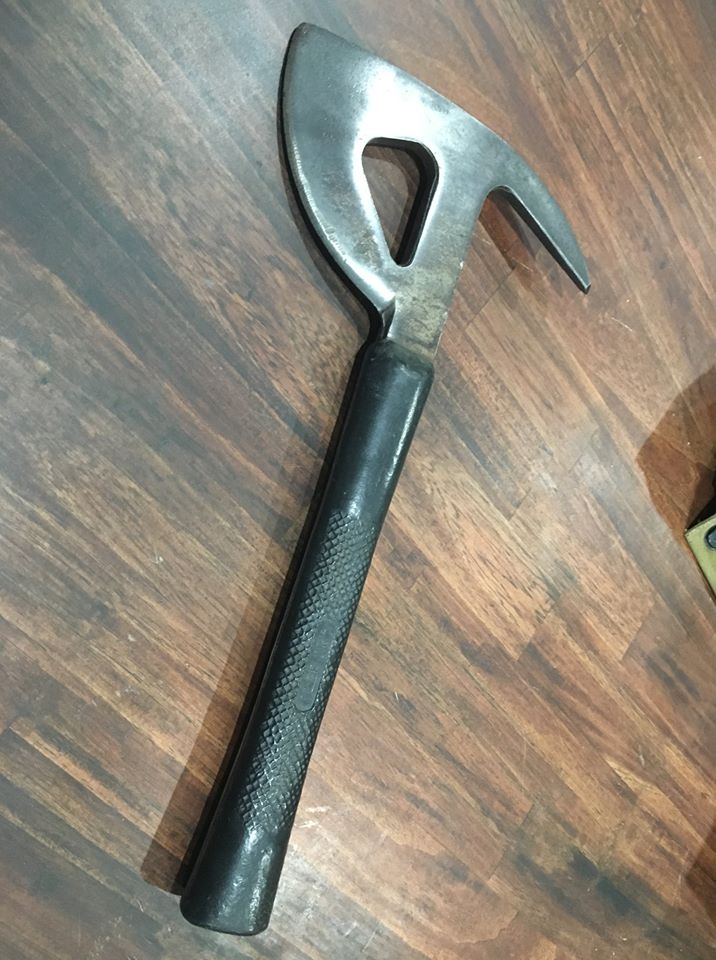

Upon hitting the water, the crew exited through the radio compartment upper hatch, while the pilots excited through their side windows. The crash axe was stowed in the cockpit to aid in their escape, if necessary.

Lucky Thirteen‘s 42D8331 crash axe.

Photo taken 29 February 2020.

Followers of our work may recall that we were able to complete Lucky Thirteen‘s SCR-578-A stowage kit in March 2023. On B-17Fs, the Gibson Girl Emergency Radio was stowed behind Station 6, just beside the ball turret. B-17Gs, carrying the SCR-578-B (which used a different bag), usually stowed the unit in the radio compartment.

Photo taken 16 May 2024.

A Boeing B-17 flight crew undergoing a life boat drill. The baffle separating the life raft from its accessory bag can be seen in the stowage compartment here. Because this is a metal baffle, as opposed to a wooden one, it suggests that this is an older B-17.

Note the airman on the right – he is holding an older style, two-bag Gibson Girl emergency radio.

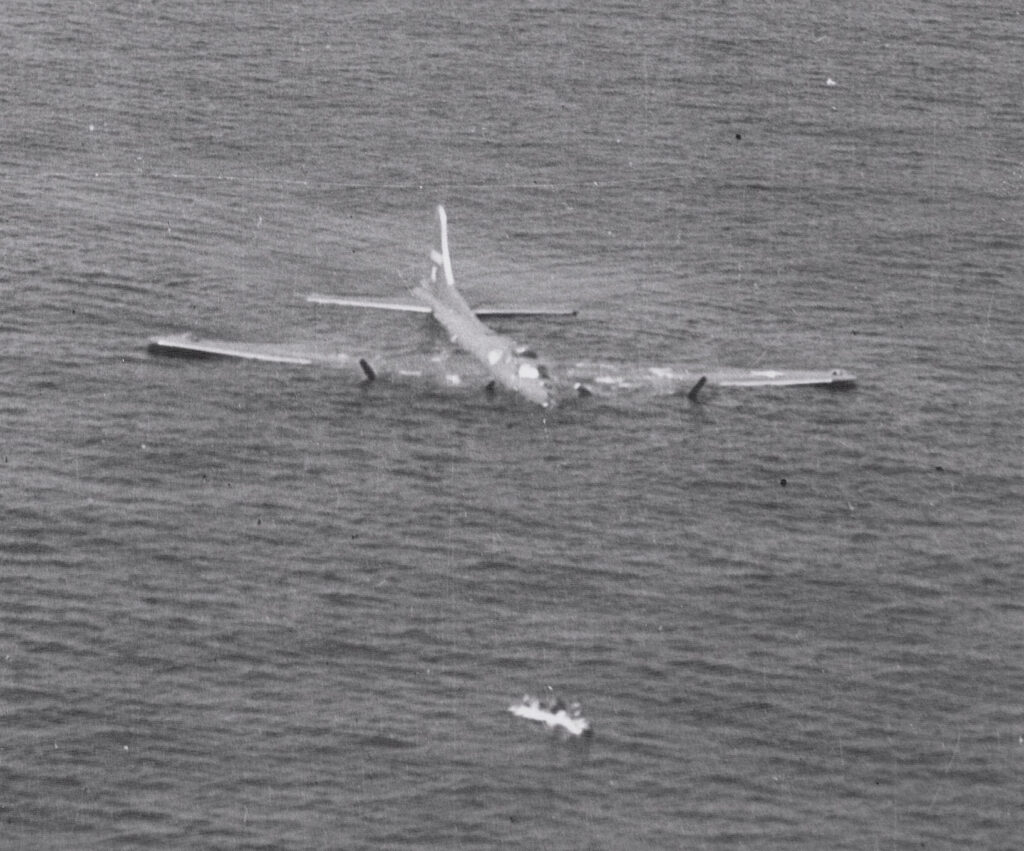

Hell-Lena (42-29981, 92BG) ditches into the English Channel on 26 July 1943 with eight survivors. The waters of her ditching are calmer than most.

The crew of 41-24362 (381BG) were the first Americans to survive a blue water ditching in the European Theater of Operations, doing so on 9 October 1942. Due to better visibility, US bombers were more likely to survive ditchings than British ones (with the notable exception of the Consolidated B-24, which tended to break in half), and with the numbers of ditchings increasing, an official “Goldfish Club” was founded by Charles A. Roberston, an employee of P. B. Cow & Co. (manufacturers of air-sea rescue equipment), the following January. Club members had to present evidence of a blue-water ditching or bailout, entitling the member to wear a goldfish pendant on their uniform. Some 450 8AF bombers made emergency ditchings by war’s end.

Unlike the ETO, air operations in the Pacific were flown almost entirely over water, which meant that even the slightest of problems could result in the loss of an entire crew. Compared to the 150 mi and 990 mi widths of the English Channel and Mediterranean Sea (both figures representing their widest points), 20AF strikes were forced to fly a distance of some 1,619 mi over water. Iwo Jima offered safe haven to the unreliable B-29s, but being 812 mi from the Marianas, the island was little more than a halfway point. One of the more creative solutions introduced were modified Boeing B-17s carrying Higgins A-1 lifeboats under their fuselage. First used on 31 March 1945 off the coast of Holland, SB-17s supplemented USN submarine, destroyer, and flying boat patrols, remaining in service well into the 1950s until replaced by rescue helicopters.

The newly arrived Type A-3 Life Raft, unrolled and ready to inflate.

Photo taken 10 January 2025.

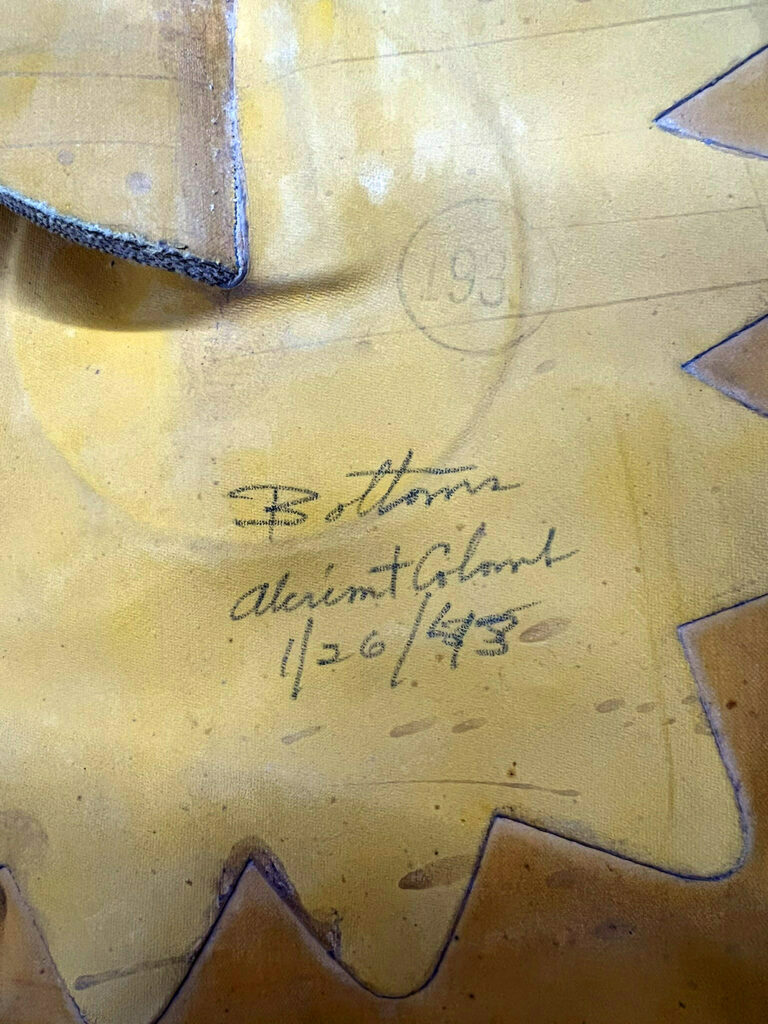

An inspection signature on the raft, dated 26 January 1943.

The name is rather unusual. It would certainly be nice if we can identify this individual.

Photo taken 10 January 2025.

The stenciled markings on the bow of the newly acquired A-3 Life Raft.

The emergency hand pump has been stowed in the straps where the CO2 cylinder would originally be held. We have a postwar life raft cylinder, whose valve mechanism is identical to a wartime one, but the cylinder is longer than the wartime variant and does not fit properly.

Photo taken 11 January 2025.

It is difficult to put into words the true horrors of a blue water ditching, as practice drills and photos in calm inland waters hardly do the experience justice. 2LT Edward Field, who served with the 384BG (the same unit as Lucky Thirteen), became an accomplished writer after the war, and we STRONGLY recommend our followers read the poem recounting his ditching experience.

On 3 January 1945, the US 8AF launched 1,003 B-17s and 434 B-24s, escorted by 44 Republic P-47s and 904 North American P-51s, against the railyards of Berlin and the BRABAG refineries of Magdeburg. Field was part of the force targeting Berlin’s Tempelhof railyard. Known as Operation THUNDERCLAP, the 1AD was led by S-3 91BG LTC Marvin D. Lord aboard “R-Roger” (42-97632) and the 3AD by CO 418BS MAJ Robert Rosenthal aboard “J-Jig” (44-8379, 100BG). In accordance with previously established policy, the B-24s of the 2AD bombed the Magdeburg refineries rather than overfly Berlin.

Launched to support the Soviet advance into Germany, THUNDERCLAP was, in actuality, the first US 8AF strike to actively target urban areas with a psychological goal rather than an economic/logistical one. No German fighter interceptions took place and the government quarter of Berlin was heavily damaged. While THUNDERCLAP was unsuccessful in generating a political collapse, follow-ups on eastern German cities continued throughout the next month, with the 1,329-strong attack of 18 March being the largest strike on the German capital of the war. (2,893 killed)

Field’s aircraft, The Challenger (42-102501), was one of 27 bombers lost this day, all from AAA ground fire. Attempting to return to her base in England, Challenger succumbed to her wounds and ditched in the English Channel. With only one of the A-3 rafts properly inflating, the crew were at sea for some four hours before rescue by the cutter RML-523. In that period, two died from exposure (pilot 2LT Robert C. Long and ball turret gunner SGT Jack C. Cook) and one was lost in the heavy waves (radio operator SGT Fred A. Maki).

With too many people for the available raft space, Field only survived by exchanging his position in the water with Cook. Upon return, Field was placed in a flak house for psychological recovery throughout the remainder of February. Returning to duty, Field completed 24 additional combat missions, flying up through the end of the war in Europe.

Still actively working, Field turned 100 years old on 7 June 2024.

Read Field’s poem about the ditching of Challenger.

We look forward to putting this piece on display for visitors. One day, when we have a proper museum facility, we will construct a detailed display showcasing emergency supplies for heavy bomber crews. After all, there is much, much more to this subject than can be shown in this simple update. Till then, we press on.

As the 384BG motto said – keep the show on the road.

Photo taken 10 January 2025.